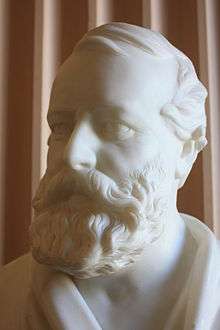

Thomas Laycock (physiologist)

Prof Thomas Laycock FRSE FRCPE (10 August 1812 – 21 September 1876) was an English physician and neurophysiologist who was a native of Bedale near York. Among medical historians, he is best known for his influence on John Hughlings Jackson and the psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne. Laycock's interests were the nervous system and psychology; he is known as one of the founders of physiological psychology. He was the first to formulate the concept of reflex action within the brain,[1] and is also known for his classification of mental illnesses.[2]

Life

Laycock was born on 10 August 1812 in Wetherby, Yorkshire, and was the son of Wesleyan minister Rev Thomas Laycock.[3] He attended the Wesleyan Academy on Woodhouse Grove in West Yorkshire.[4] At the age of fifteen, Laycock trained as an apprentice surgeon-apothecary under a Mr. Spence.[3] He went on to study at the University College in London and furthered his training in Paris in 1834 for two more years, where his instructors included Alfred Armand Velpeau (1795–1867) and Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis (1787–1872), renowned as an initiator of statistics.[5] While in Paris, Laycock studied anatomy and physiology under Jacques Lisfranc de St. Martin and Velpeau at la Pitié.[3]

In the spring of 1837, Laycock began to learn German to further his readings beyond English and French literature. In 1839, he went to Germany and received his doctorate degree under Professor Karl Friedrich Heinrich Marx at University of Göttingen in Lower Saxony, Germany.[3] Throughout 1839 to 1840, Laycock published many papers on hysteria and other mental illnesses.[2]

In his final paper on hysteria, Laycock wrote about the effects of hysteria on consciousness seen in comas, delirium, hallucinations, and somnambulism.[2] This final paper introduced the revolutionary concept that stimuli to the brain could invoke actions in the subject without the subject being aware of them. This concept steered away from the notion of man as a unique spiritual human being, and saw man as more automated and animalistic.[2]

After receiving his doctorate degree in 1839, Laycock returned to York working as a physician at the York Dispensary and lecturer of medicine at York Medical School.[5] During his time at the York Dispensary, he earned himself a reputation as a skilled physician, as well as a profound thinker, medical scientist, and prolific writer.[6]

In 1852, Laycock first encountered Hughlings Jackson, a new student; he also taught Jonathan Hutchinson whom Jackson was to meet in 1859 and share a house with at 14 Finsbury Circus, London for three years.

In 1855, the position of chair of medicine at the University of Edinburgh became open. The position was highly desired and candidates would canvas for the spot.[2] Of eight potential contestants, Laycock was selected by the Edinburgh Town Council; however, he was not generally accepted by the public or by the people of the profession.[6] Despite the antagonism, Laycock maintained his reputation as a prolific writer in medical, philosophical, and psychological writings up until his death in 1876.

Laycock set up a course for medical psychology and mental diseases as a professor of medicine at Edinburgh.[3] His course was not well received by the medical students at Edinburgh. The medical students preferred being taught straightforward principles to help prepare for examinations. On the other hand, Laycock preferred to present an abstract, broad view of medicine in the hopes that his students would learn through independent reading without someone forcing them to learn.[6]

In Edinburgh, Laycock was friendly with the asylum reformer William A.F. Browne (1805-1885) and was a major influence on his son, the psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne (1840-1938)

During his mid-forties, Laycock suffered from phthisis (tuberculosis). His physicians told him that he did not have long to live, however, he went on to live for another twenty years.[3] Due to tuberculosis of the knee, his left knee had to be amputated. He insisted on having the operation done without anesthetics, and he spent the last decade of his life as an amputee.[3]

His wife Ann died in 1869 and is buried in York.

Laycock died at home, 13 Walker Street, in Edinburgh's West End.[7]

He is buried a short distance from his home, in one of the upper terraces of St Johns Episcopal Church at the west end of Princes Street.

Teachings

Reflex function of the brain

Following the work of Robert Whytt and Marshall Hall, Laycock studied the reflex arc in relation to the nervous system.[5] While Hall believed that the reflex arc was mediated by the spinal cord, separate from the cerebrum, Laycock argued that the brain underwent the same reflex patterns as the rest of the nervous system.[3] After learning the German language, he translated books by Johann August Unzer, who studied afferent and efferent reflexes. Unzer centralised the nervous system in the spinal cord, such that reflexes could occur even without a functional brain, which only controls conscious activity.[5] Laycock disagreed with Unzer's centralisation in the spinal root ganglia; Laycock stated: "The brain, although the organ of consciousness, was subject to the laws of reflex action and in this respect it did not differ from other ganglia of the nervous system."[6]

Nature and methodology

Laycock was a teleologist. He also held a fundamental belief in the "unity of nature", and saw nature as working through an unconsciously acting principle of organisation. Through his teleological approach, he argued that the origins of the nervous system were based on a natural force which he named the "Unconsciously Acting Principle for Intelligence."[3] This force provided a plan for organism construction, regulated organisms based on survival instinct, and acted on the brain to provoke the phenomena of thought. Laycock saw nature as purposeful in creating this force, which ultimately results in a self-conscious mind, and an unconscious intelligence where reflexes were seeded.[3] Because of his teleological approach to seeing nature through a lens of purpose, Laycock used observation as his principal method of scientific inquiry. He did not advocate for microscopic experimentation, which he saw as unnecessary in studying nature's biological forces. Rather, he preferred passive observation of purposeful phenomena in nature, from which theories could be inducted.[3]

Classification of psychiatric disorders

In 1863, Laycock published a paper on the classification of psychiatric disorders. On the classification, he said: "If we further analyse the standard as applied to the naming and classification of mental diseases in general, we find it includes attributes or qualities in common with others of the same age, sex, or social position".[2] Laycock recognised that many factors were included in classification, and therefore absolute standards were not feasible.

Laycock was also aware of the different possible approaches in classification, but he used a biological and neurological approach to classification. He classified insanity into three types: orectic insanity, thymic insanity, and phrenic insanity.[2] Each type of insanity was associated with a disorder in encephalic centers that controlled instincts, feelings, or reason.

The biological approach to classifying mental disorders was due to Laycock's belief that the mind was a result of the brain. On insanity, his definition was: "a chronic disorder of the brain by which the mental condition of the individual is so modified that he is deprived wholly or in part of common sense."[2] He explained moral insanity and mania through the concept of "reversed evolution," a concept that was later furthered by John Hughlings Jackson.[2]

Laycock became president of the Medico Psychological Association in 1869.[2] He thought that people who were mentally handicapped could also be mentally ill, which was not yet a generally accepted idea during his time.

Legacy

Historians have a hard time crediting Laycock for his findings in the existence of the cerebral reflex and the continuity of the nervous system throughout the animal species because of his non-scientific methodology.[3] Laycock's writing style was also very dense, and difficult to understand due to the lack of brevity.[2] In his writings, he would include many philosophical ideas and expressions, which would hinder the understanding of his concepts.

Laycock's ideas reached modern day acceptance through his student John Hughlings Jackson, who recast the concept of the continuity of nervous systems in animals through evolutionary proof.[3] Jackson's scientific approach gained much more acceptance than Laycock's philosophical, observational approach. Laycock generalised the reflex patterns of the entire nervous system and the synthesis of nervous function. Ivan Pavlov, Charles Scott Sherrington, and Sigmund Freud later expanded upon Laycock's philosophical observations of nervous function synthesis.[6]

The honors received by Laycock include: fellowship in the Royal Society, Edinburgh, fellowship in the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and Physician in Ordinary to the Queen of Scotland.[6]

Publications

- Religio Medicorum: a Critical Essay on Medical Ethics (1848)

- The Social and Political Relations of Drunkenness (1857)

- Mind and Brain (1860)

Notes

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0 902 198 84 X.

- James, F.E. (1998). "Thomas Laycock, psychiatry and neurology". History of Psychiatry. 9: 491–502. doi:10.1177/0957154x9800903604.

- Leff, Alex (1991). "Thomas Laycock and the cerebral reflex: a function arising from and pointing to the unity of Nature". History of Psychiatry. 2: 385–407. doi:10.1177/0957154x9100200803.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0 902 198 84 X.

- Pearce, JMS (2002). "Thomas Laycock (1812-1876)". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 73: 303. doi:10.1136/jnnp.73.3.303. PMC 1738035. PMID 12185163.

- "Thomas Laycock (1812-1876), Mental Physiologist, Medical Psychologist". Journal of the American Medical Association. 205 (5): 103–104. 1968. doi:10.1001/jama.205.5.301.

- https://www.royalsoced.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/biographical_index/fells_indexp2.pdf

References

- Seccombe, Thomas (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 32. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Andrew Hodgkiss (1 January 2000). From Lesion to Metaphor: Chronic Pain in British, French and German Medical Writings, 1800-1914. Rodopi. pp. 91–. ISBN 90-420-0821-0.

- Pearce, JMS (2002). "Thomas Laycock (1812–1876)". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 73: 303. doi:10.1136/jnnp.73.3.303. PMC 1738035. PMID 12185163.

- British Medical Journal (30 September 1876) Obituary.

- James, Frederick Ernest (1998). "The Life and Work of Thomas Laycock 1812-1876". London. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)