Theory of planned behavior

In psychology, the theory of planned behaviour (abbreviated TPB) is a theory that links one's beliefs and behaviour.

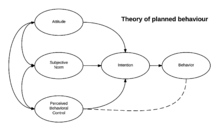

The theory states that attitude, subject norms, and perceived behavioural control, together shape an individual's behavioural intentions and behaviours.

The concept was proposed by Icek Ajzen to improve on the predictive power of the theory of reasoned action by including perceived behavioural control.[1] It has been applied to studies of the relations among beliefs, attitudes, behavioural intentions and behaviours in various fields such as advertising, public relations, advertising campaigns, healthcare, sport management and sustainability.

History

Extension from the theory of reasoned action

The theory of planned behaviour was proposed by Icek Ajzen (1985) through his article "From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour."[2] The theory was developed from the theory of reasoned action, which was proposed by Martin Fishbein together with Icek Ajzen in 1980. The theory of reasoned action was in turn grounded in various theories of attitude such as learning theories, expectancy-value theories, consistency theories (such as Heider's balance theory, Osgood and Tannenbaum's congruity theory, and Festinger's dissonance theory) and attribution theory.[3] According to the theory of reasoned action, if people evaluate the suggested behaviour as positive (attitude), and if they think their significant others want them to perform the behaviour (subjective norm), this results in a higher intention (motivations) and they are more likely to do so. A high correlation of attitudes and subjective norms to behavioural intention, and subsequently to behaviour, has been confirmed in many studies.[4]

A counter-argument against the high relationship between behavioural intention and actual behaviour has also been proposed, as the results of some studies show that,[5] because of circumstantial limitations, behavioural intention does not always lead to actual behaviour. Namely, since behavioural intention cannot be the exclusive determinant of behaviour where an individual's control over the behaviour is incomplete, Ajzen introduced the theory of planned behaviour by adding a new component, "perceived behavioural control". By this, he extended the theory of reasoned action to cover non-volitional behaviours for predicting behavioural intention and actual behaviour.

The most recent addition of a third factor, perceived behavioural control, refers to the degree to which a person believes that they control any given behaviour (class notes). The theory of planned behaviour suggests that people are much more likely to intend to enact certain behaviours when they feel that they can enact them successfully. Increased perceived behavioural control is a mix of two dimensions: self-efficacy and controllability (170). Self-efficacy refers to the level of difficulty that is required to perform the behaviour, or one's belief in their own ability to succeed in performing the behaviour. Controllability refers to the outside factors, and one's belief that they personally have control over the performance of the behaviour, or if it is controlled by externally, uncontrollable factors. If a person has high perceived behavioural control, then they have an increased confidence that they are capable of performing the specific behaviour successfully.

The theory has since been improved and renamed the reasoned action approach by Azjen and his colleague Martin Fishbein.

Extension of self-efficacy

In addition to attitudes and subjective norms (which make the theory of reasoned action), the theory of planned behaviour adds the concept of perceived behavioural control, which originates from self-efficacy theory (SET). Self-efficacy was proposed by Bandura in 1977,[6] which came from social cognitive theory. According to Bandura, expectations such as motivation, performance, and feelings of frustration associated with repeated failures determine effect and behavioural reactions. Bandura separated expectations into two distinct types: self-efficacy and outcome expectancy.[7] He defined self-efficacy as the conviction that one can successfully execute the behaviour required to produce the outcomes. The outcome expectancy refers to a person's estimation that a given behaviour will lead to certain outcomes. He states that self-efficacy is the most important precondition for behavioural change, since it determines the initiation of coping behaviour. Previous investigations have shown that peoples' behaviour is strongly influenced by their confidence in their ability to perform that behaviour.[8] As the self-efficacy theory contributes to explaining various relationships between beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviour, the SET has been widely applied to health-related fields such as physical activity and mental health in preadolescents,[9] and exercise.[10][11][12]

Concepts of key variables

Normative beliefs and subjective norms

- Normative belief: an individual's perception of social normative pressures, or relevant others' beliefs that they should or should not perform such behaviour.

- Subjective norm: an individual's perception about the particular behaviour, which is influenced by the judgment of significant others (e.g., parents, spouse, friends, teachers).[13]

Control beliefs and perceived behavioural control

- Control beliefs: an individual's beliefs about the presence of factors that may facilitate or hinder performance of the behaviour.[14] The concept of perceived behavioural control is conceptually related to self-efficacy.

- Perceived behavioural control: an individual's perceived ease or difficulty of performing the particular behaviour.[1] It is assumed that perceived behavioural control is determined by the total set of accessible control beliefs.

Behavioural intention and behaviour

- Behavioural intention: an indication of an individual's readiness to perform a given behaviour. It is assumed to be an immediate antecedent of behaviour.[15] It is based on attitude toward the behaviour, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control, with each predictor weighted for its importance in relation to the behaviour and population of interest.

- Behaviour: an individual's observable response in a given situation with respect to a given target. Ajzen said a behaviour is a function of compatible intentions and perceptions of behavioural control in that perceived behavioural control is expected to moderate the effect of intention on behaviour, such that a favorable intention produces the behaviour only when perceived behavioural control is strong

Conceptual / operational comparison

Perceived behavioural control vs. self-efficacy

As Ajzen (1991) stated in the theory of planned behaviour, knowledge of the role of perceived behavioural control came from Bandura's concept of self-efficacy. More recently, Fishbein and Cappella stated[16] that self-efficacy is the same as perceived behavioural control in his integrative model, which is also measured by items of self-efficacy in a previous study.[17]

In previous studies, the construction and the number of item inventory of perceived behavioural control have depended on each particular health topic. For example, for smoking topics, it is usually measured by items such as "I don't think I am addicted because I can really just not smoke and not crave for it," and "It would be really easy for me to quit."

The concept of self-efficacy is rooted in Bandura's social cognitive theory.[18] It refers to the conviction that one can successfully execute the behaviour required to produce the outcome. The concept of self-efficacy is used as perceived behavioural control, which means the perception of the ease or difficulty of the particular behaviour. It is linked to control beliefs, which refers to beliefs about the presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of the behaviour.

It is usually measured with items which begins with the stem, "I am sure I can ... (e.g., exercise, quit smoking, etc.)" through a self-report instrument in their questionnaires. Namely, it tries to measure the confidence toward the probability, feasibility, or likelihood of executing given behaviour.

Attitude toward behaviour vs. outcome expectancy

The theory of planned behaviour specifies the nature of relationships between beliefs and attitudes. According to these models, people's evaluations of, or attitudes toward behaviour are determined by their accessible beliefs about the behaviour, where a belief is defined as the subjective probability that the behaviour will produce a certain outcome. Specifically, the evaluation of each outcome contributes to the attitude in direct proportion to the person's subjective possibility that the behaviour produces the outcome in question.[19]

Outcome expectancy was originated from the expectancy-value model. It is a variable-linking belief, attitude, opinion and expectation. The theory of planned behaviour's positive evaluation of self-performance of the particular behaviour is similar to the concept to perceived benefits, which refers to beliefs regarding the effectiveness of the proposed preventive behaviour in reducing the vulnerability to the negative outcomes, whereas their negative evaluation of self-performance is similar to perceived barriers, which refers to evaluation of potential negative consequences that might result from the enactment of the espoused health behaviour.

Social influence

The concept of social influence has been assessed by the social norm and normative belief in both the theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behaviour. Individuals' elaborative thoughts on subjective norms are perceptions on whether they are expected by their friends, family and the society to perform the recommended behaviour. Social influence is measured by evaluation of various social groups. For example, in the case of smoking:

- Subjective norms from the peer group include thoughts such as, "Most of my friends smoke," or "I feel ashamed of smoking in front of a group of friends who don't smoke";

- Subjective norms from the family include thoughts such as, "All of my family smokes, and it seems natural to start smoking," or "My parents were really mad at me when I started smoking"; and

- Subjective norms from society or culture include thoughts such as, "Everyone is against smoking," and "We just assume everyone is a nonsmoker."

While most models are conceptualized within individual cognitive space, the theory of planned behaviour considers social influence such as social norm and normative belief, based on collectivistic culture-related variables. Given that an individual's behaviour (e.g., health-related decision-making such as diet, condom use, quitting smoking and drinking, etc.) might very well be located in and dependent on the social networks and organization (e.g., peer group, family, school and workplace), social influence has been a welcomed addition.

Model

Human behaviour is guided by three kinds of consideration: behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. In their respective aggregates, behavioural beliefs produce a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward the behaviour, normative beliefs result in a subjective norm, and control beliefs gives rise to perceived behavioural control.

In combination, the attitude toward the behaviour, the subjective norm, and the perceived behavioural control lead to the formation of a behavioural intention.[15] In particular, perceived behavioural control is presumed not only to affect actual behaviour directly, but also to affect it indirectly through behavioural intention.[20]

As a general rule, the more favorable the attitude toward behaviour and the subjective norm, and the greater the perceived behavioural control, the stronger the person's intention to perform the behaviour should be. Finally, given a sufficient degree of actual control over the behaviour, people are expected to carry out their intentions when the opportunity arises.[15]

Formula

In a simple form, behavioural intention for the theory of planned behaviour can be expressed as the following mathematical function:

The three factors being proportional to their underlying beliefs:[1]

| BI: Behavioural intention

A: Attitude toward behaviour b: the strength of each belief concerning an outcome or attribute e: the evaluation of the outcome or attribute SN: Subjective norm n: the strength of each normative belief of each referent m: the motivation to comply with the referent PBC: Perceived Behavioural Control c: the strength of each control belief p: the perceived power of the control factor w : empirically derived weight/coefficient |

To the extent that it is an accurate reflection of actual behavioural control, perceived behavioural control can, together with intention, be used to predict behaviour.

| B: Behaviour

BI: Behavioural intention PBC: Perceived Behavioural Control c: the strength of each control belief p: the perceived power of the control factor w : empirically derived weight/coefficient |

Evaluation of the theory

Strengths

The theory of planned behaviour can cover people's non-volitional behaviour which cannot be explained by the theory of reasoned action.

An individual's behavioural intention cannot be the exclusive determinant of behaviour where an individual's control over the behaviour is incomplete. By adding "perceived behavioural control", the theory of planned behaviour can explain the relationship between behavioural intention and actual behaviour.

Several studies found that the TPB would help better predict health-related behavioural intention than the theory of reasoned action.[21] The TPB has improved the predictability of intention in various health-related fields such as condom use, leisure, exercise, diet, etc.

In addition, the theory of planned behaviour as well as the theory of reasoned action can explain the individual's social behaviour by considering "social norm" as an important variable.

Limitations

Some scholars claim that the theory of planned behaviour is based on cognitive processing, and they have criticised the theory on those grounds. More recently, some scholars criticize the theory because it ignores one's needs prior to engaging in a certain action, needs that would affect behaviour regardless of expressed attitudes. For example, one might have a very positive attitude towards beefsteak and yet not order a beefsteak because one is not hungry. Or, one might have a very negative attitude towards drinking and little intention to drink and yet engage in drinking as one is seeking group membership.

Also, one's emotions at the interviewing or decision-making time are ignored despite being relevant to the model as emotions can influence beliefs and other constructs of the model. Still, poor predictability for health-related behaviour in previous health research seems to be attributed to poor application of the model, associated methods and measures. Most of the research is correlational, and more evidence based on experimental studies is welcome although experiments, by nature, lack external validity because they prioritize internal validity.[22]

Indeed, some experimental studies challenge the assumption that intentions and behaviour are merely consequences of attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control. To illustrate, in one study,[23] participants were prompted to form the intention to support a specific environmental organisation—such as to sign a petition. After this intention was formed, attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control shifted. Participants became more likely to report positive attitudes towards this organisation and were more inclined to assume their social group would share comparable attitudes.[23] These findings imply the associations between the three key elements—attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioural control—and intentions may be bi-directional.

Applications of the theory

So far, the theory of planned behaviour has more than 1200 research bibliographies in academic databases such as Communication & Mass Media Complete, Academic Search Premier, PsycARTICLES, Business Source Premier, PsycINFO, and PsycCRITIQUES.

Health-related behaviours

In particular, several studies found that the TPB would better help to predict health-related behavioural intention than the theory of reasoned action (TRA)[21] given that the TPB has improved the predictability of intention in various health-related fields such as condom use,[24][25] leisure,[26] exercise,[27] and diet,[28] where the attitudes and intentions to behave in a certain way are mediated by goals rather than needs. For example, the goal to lose 10 kg in weight by the end of March, therefore a positive attitude and intention towards dieting. However, if a need is taken in calculation (health related or partner finding) the TPB fails. Assuming that one's need is to find a partner, if the partner is found who favours a person who is overweight, or does not mind one's weight, then despite an individual's positive attitude towards losing weight, they won't engage in a such behaviour for fear of losing the new partner, the main reason for engaging in dieting in first place.

The theory of planned behaviour can also be applied in area of applied nutrition intervention. In a study by Sweitzer, et al,[29] TPB (in conjunction with SCT) was utilized to encourage parents to include more fruit, vegetables and whole grains (FVWG) in packed lunches of preschool children. Behavioural constructs of TPB were used to develop intervention strategies. Knowledge/behavioural control, self-efficacy/perceived behavioural control, subjective norms and intentions were measured to see effects on behaviour. The results found a significant increase in vegetables and whole grains packed in lunches when interventions were planned using the TPB constructs. Psychosocial variables were useful predictors of lunch packing behaviours of parents and this study provided a divergent application of model-exploration of an area of parental behaviour as a role in the development of young children's dietary behaviours. In a study by McConnon, et al,[30] the application of the TPB was used to prevent weight regain in an overweight cohort who recently experienced a significant weight loss. Using the constructs of TPB, it was found that perceived need to control weight is the most positive predictor of behaviour for weight maintenance. The TPB model can be used to predict weight gain prevention expectation in an overweight cohort. The TPB can also be utilized to measure behavioural intention of practitioners in promoting specific health behaviours. In this study by Chase,[31] dietitians' intentions to promote whole grain foods was studied. It was found that the strongest indicator of intention of dietitians to promote whole grain foods was the construct of normative beliefs with 97% of dietitians indicating that health professionals should promote whole grains and 89% wanted to comply with this belief. However, knowledge and self-efficacy of instituting this belief was faulted with only 60% of dietitians being able to correctly identify a whole grain product from a food label, 21% correctly identifying current recommendations and 42% of dietitians did not know there was a recommendation for whole grain consumption. Although the response rate to complete mailed surveys for this study was low (39%), the results provided preliminary data on the strong effect of normative beliefs on dietitian intentions to promote whole grain and the need for nutrition need for additional education for practicing dietitians focusing on increase knowledge and self-efficacy for promoting whole grains.

More recent research has looked at TPB and predicting college students' intention to use e-cigarettes. Studies found that attitudes toward smoking and social norms significantly predicted college students' behaviour, as TPB suggests. Positive attitudes toward smoking and normalizing the behaviour was, in part, helped by advertisements on the Internet. With this information and foundation of TPB, smoking prevention campaigns have started to be implemented specifically targeting college students collectively, not just as individuals.[32]

The theory of planned behaviour model is thus a very powerful and predictive model for explaining human behaviour. That is why the health and nutrition fields have been using this model often in their research studies. In one study, utilizing the theory of planned behaviour, the researchers determine obesity factors in overweight Chinese Americans.[33] Intention to prevent becoming overweight was the key construct in the research process. It is important that nutrition educators provide the proper public policies in order to provide good tasting, low-cost, healthful food.

The TPB also shows good applicability in regards to antisocial behaviours, such as using deception in the online environment.[34] However, as the TPB relies on self-reports, there is evidence to suggest the vulnerability of such data to self-presentational biases. To a great extent, this has been ignored in the literature pertaining to the TRA/TPB, in spite of the threat to the validity and reliability of the models. More closely related to the concerns of the present study, Hessing, ElVers, and Weigel (1988) examined the TRA in relation to tax evasion and contrasted self-reports with official documentation. Findings indicated that while attitudes and subjective norms correlate with self-reported behaviour, it does not correlate with documentary evidence, in spite of considerable effort to maintain the anonymity of respondents. The implication was that self-reports of behaviour were unreliable, compared with more objective behaviour measures (see also Armitage & Conner, 1999a, 1999b; Norwich & Rovoli, 1993; Pellino, 1997).

Environmental psychology

Another application of the theory of planned behaviour is in the field of environmental psychology. Generally speaking, actions that are environmentally friendly carry a positive normative belief. That is to say, sustainable behaviours are widely promoted as positive behaviours. However, although there may be a behavioural intention to practice such behaviours, perceived behavioural control can be hindered by constraints such as a belief that one's behaviour will not have any impact.[35][36] For example, if one intends to behave in an environmentally responsible way but there is a lack of accessible recycling infrastructure, perceived behavioural control is low, and constraints are high, so the behaviour may not occur. Applying the theory of planned behaviour in these situations helps explain contradictions between sustainable attitudes and unsustainable behaviour.

Further research has concluded that attitudes toward climate change, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms are associated with the intention to adopt a pro-environmental behaviour. This type of information can be applied to policy-making and other environmental efforts.[37]

Economics

It has been applied in the field of economics to examine the translation of fertility intentions into residential relocation and fertility.[38]

Voting behaviour

The theory of planned behaviour is also used in the field of political science to predict voter turnout and behaviour. It is also the most effective framework for understanding legislator behaviour. In order to effectively advocate for certain issues, supporters can use information shaped by TPB to create meaningful communication with legislators.[39]

Important steps

When applying the TPB as a theoretical framework, certain steps should be followed to promote increased validity of results. First, target behaviour should be specified in terms of action, target, context, and time. For example, the goal might be to "consume at least one serving of whole grains during breakfast each day in the forthcoming month". In this statement, "consuming" is the action, "one serving of whole grains" is the target, "during breakfast each day" is the context, and "in the forthcoming month" is the time. Once a goal is specified, an elicitation phase can be used to identify salient issues. The pertinent and central beliefs for a certain behaviour may be very different for different populations. Therefore, conducting open-ended elicitation interviews is one of the most crucial steps in applying the TPB. Elicitation interviews help to identify relevant behavioural outcomes, referents, cultural factors, facilitators, and barriers for each particular behaviour and target population under investigation.[40] The following are sample questions that may be used during an elicitation interview:[40]

- What do you like/ dislike about behaviour X?

- What are some disadvantages of doing behaviour X?

- Who would be against your doing behaviour X?

- Who can you think of that would do behaviour X?

- What things make it hard for you to do behaviour X?

- If you want to do behaviour X, how certain are you that you can?

However, the action, target, context and time construct shows little applicability when one engages in consuming luxury or fashion goods, especially as one's need is not present. For example, the goal might be to "buy three pairs of luxury high heels in the forthcoming month". In this statement, "buying" is the action, "three pairs of high heels" is the target, "luxury goods" is the context, and "in the forthcoming month" is the time. In normal circumstances, once the goal is specified, the elicitation phase can be used to identify salient issues but not in this case as the need behind buying the shoes (wedding, sport, to show off, to feel good, to match with an existing outfit) primes in the decision making and therefore in the resulted behaviour.

Also, while the pertinent and central beliefs for a certain behaviour may be very different for different populations, the questionnaire can then be designed, based on results from the elicitation interview, to measure model constructs with attention to cultural issues. After implementation of the questionnaire, thorough analysis should be conducted to assess whether the intervention influenced model constructs associated with intention and behaviour.[40] Results and findings from the analysis can be used to develop effective interventions for eliciting behavioural change, especially within nutrition and health but not for luxury or fashion goods where one's need behind his purchase intentions (behaviour) are in most social context cases to associate, dissociate or show status.

See also

References

- Ajzen, Icek (1991). "The theory of planned behavior". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 50 (2): 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior. Berlin, Heidelber, New York: Springer-Verlag. (pp. 11-39).

- Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Sheppard, B.H.; Hartwick, J.; Warshaw, P.R. (1988). "The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research". Journal of Consumer Research. 15 (3): 325–343. doi:10.1086/209170.

- Norberg, P. A.; Horne, D. R.; Horne, D. A. (2007). "The privacy paradox: Personal information disclosure intentions versus behaviors". Journal of Consumer Affairs. 41 (1): 100–126. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00070.x.

- Bandura, A. (1977). "Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change". Psychological Review. 84 (2): 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191. PMID 847061.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Bandura, A.; Adams, N. E.; Hardy, A. B.; Howells, G. N. (1980). "Tests of the generality of self-efficacy theory". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 4 (1): 39–66. doi:10.1007/bf01173354.

- Annesi, James J. (2005). "Correlations of Depression and Total Mood Disturbance with Physical Activity and Self-Concept in Preadolescents Enrolled in an After-School Exercise Program". Psychological Reports. 96 (3_suppl): 891–898. doi:10.2466/pr0.96.3c.891-898. PMID 16173355.

- Gyurcsik, N. C.; Brawley, L. R. (2000). "Mindful Deliberation About Exercise: Influence of Acute Positive and Negative Thinking1". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 30 (12): 2513–2533. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02448.x.

- Rodgers, W. M.; Brawley, L. R. (1996). "The influence of outcome expectancy and self-efficacy on the behavioral intentions of novice exercisers". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 26 (7): 618–634. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb02734.x.

- Stanley, M. A.; Maddux, J. E. (1986). "Cognitive processes in health enhancement: Investigation of a combined protection motivation and self-efficacy model". Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 7 (2): 101–113. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0702_2.

- Amjad, N.; Wood, A.M. (2009). "Identifying and changing the normative beliefs about aggression which lead young Muslim adults to join extremist anti-Semitic groups in Pakistan" (PDF). Aggressive Behavior. 35 (6): 514–519. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.332.6476. doi:10.1002/ab.20325. PMID 19790255.

- Ajzen, I (2001). "Nature and operation of attitudes". Annual Review of Psychology. 52 (1): 27–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27. PMID 11148298.

- Ajzen, I (2002). "Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 32 (4): 665–683. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x.

- Fishbein, M., & Cappella, J. N. (2006). The role of theory in developing effective health communications. Journal of Communication, 56(s1), S1-S17.

- Ajzen, I (2002). "Residual effects of past on later behavior: Habituation and reasoned action perspectives" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Review. 6 (2): 107–122. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0602_02.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (see article). New York: Freeman.

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. (1975). "A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes". Psychological Bulletin. 82 (2): 261. doi:10.1037/h0076477.

- Noar, S. M.; Zimmerman, R. S. (2005). "Health Behavior Theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction?". Health Education Research. 20 (3): 275–290. doi:10.1093/her/cyg113. PMID 15632099.

- Ajzen, I. (1989). Attitude structure and behavior. Attitude structure and function, 241-274.

- Sniehotta, F.F. (2009). "An experimental test of the Theory of Planned Behavior". Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 1 (2): 257–270. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01013.x.

- Sussman, Reuven; Gifford, Robert (2019). "Causality in the Theory of Planned Behavior". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 45 (6): 920–933. doi:10.1177/0146167218801363. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 30264655.

- Albarracin, D.; Johnson, B. T.; Fishbein, M.; Muellerleile, P. A. (2001). "Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of common use: a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 127 (1): 142–161. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. PMC 4780418. PMID 11271752.

- Sheeran, P.; Taylor, S. (1999). "Predicting Intentions to Use Condoms: A Meta-Analysis and Comparison of the Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior1". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 29 (8): 1624–1675. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb02045.x.

- Ajzen, I., & Driver, B. L. (1992). Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. Journal of leisure research.

- Nguyen, M. N.; Potvin, L.; Otis, J. (1997). "Regular exercise in 30-to 60-year-old men: Combining the stages-of-change model and the theory of planned behavior to identify determinants for targeting heart health interventions". Journal of Community Health. 22 (4): 233–246. doi:10.1023/A:1025196218566. PMID 9247847.

- Conner, M.; Kirk, S. F.; Cade, J. E.; Barrett, J. H. (2003). "Environmental influences: factors influencing a woman's decision to use dietary supplements". The Journal of Nutrition. 133 (6): 1978S–1982S. doi:10.1093/jn/133.6.1978s. PMID 12771349.

- Sweitzer, S.; Briley, M.; Roberts-Gray, C.; Hoelscher, D.; Harrist, R.; Staskel, D.; Almansour, F. (2011). "Psychosocial Outcomes of Lunch is in the Bag, a Parent Program for Packing Healthy Lunches for Preschool Children". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 43 (6): 536–542. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.10.009. PMC 3222455. PMID 21852196.

- McConnon, A.; Raats, M.; Astrup, A.; Bajzová, M.; Handjieva-Darlenska, T.; Lindroos, A. K.; Martinez, J. A.; Larson, T. M.; et al. (2012). "Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to weight control in an overweight cohort. Results from a pan-European dietary intervention trial (DiOGenes)" (PDF). Appetite. 58 (1): 313–318. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2011.10.017. PMID 22079178.

- Chase, K., Reicks, M., & Jones, J. (2003). Applying the theory of planned behavior to promotion of whole-grain foods by dietitians. J Am Diet Assoc. 103:1639-1642.

- Dobbs, P.D.; Jozkowski, K.N.; Hammig, B.; Blunt-Vinti, H.; Henry, L.J.; Lo, W.J.; Gorman, D.; Luzius, A. (2019). "College student e-cigarette use: A reasoned action approach measure development". American Journal of Health Behavior. 43 (4): 753–766. doi:10.5993/AJHB.43.4.9. PMID 31239018.

- Liou, D.; Bauer, K. D. (2007). "Exploratory investigation of obesity risk and prevention in Chinese Americans". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 39 (3): 134–141. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2006.07.007. PMID 17493563.

- Grieve, Rachel; Elliott, Jade (2013-04-10). "Cyberfaking: I Can, So I Will? Intentions to Fake in Online Psychological Testing". Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 16 (5): 364–369. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0271. ISSN 2152-2715. PMID 23574347.

- Koger, S. & Winter, D. N. N. (2010). The Psychology of Environmental Problems. New York: Psychology Press.

- Stern, P. C. (2005). "Understanding individuals' environmentally significant behavior". Environmental Law Reporter: News and Analysis. 35: 10785–10790.

- Masud, M.M.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Junsheng, H.; Ahmed, F.; Yahaya, S.R.; Akhtar, R.; Banna, H. (2015). "Climate change issue and the theory of planned behaviour:relationship by empirical evidence". Journal of Cleaner Production. 113: 613–623. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.080.

- Li, Ang (November 2019). "Fertility intention‐induced relocation: The mediating role of housing markets". Population, Space and Place. 25 (8). e2265. doi:10.1002/psp.2265.

- Tung, G.J.; Vernick, J.S.; Reiney, E.V.; Gielen, A.C. (2012). "Legislator voting and behavioral science theory: A systematic review". American Journal of Health Behavior. 36 (6): 823–833. doi:10.5993/AJHB.36.6.9. PMID 23026040.

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K; Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th Edition, Jossey-Bass, 2015.

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. (2001). "Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analytic review". British Journal of Social Psychology. 40 (4): 471–499. doi:10.1348/014466601164939. PMID 11795063.

- Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behaviour. In Albarracin, D.; Johnson, B.T.; Zanna M.P. (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.