Theme Park (video game)

Theme Park is a construction and management simulation video game developed by Bullfrog Productions and published by Electronic Arts in 1994. The player designs and operates an amusement park, with the goal of making money and creating theme parks worldwide. The game is the first instalment in Bullfrog's Theme series and their Designer Series.

| Theme Park | |

|---|---|

European cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Bullfrog Productions Krisalis Software (PS1 & Saturn) EA Japan (Nintendo DS) |

| Publisher(s) | Bullfrog Productions Electronic Arts Mindscape (CD32) Ocean Software (Jaguar & PAL SNES) Domark (Sega Mega CD) |

| Programmer(s) | Peter Molyneux Demis Hassabis |

| Composer(s) | Russell Shaw |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS, Amiga, 3DO, Mega Drive/Genesis, Mega CD, Amiga CD32, Mac OS, Atari Jaguar, FM Towns, Sega Saturn, PlayStation, Super NES, Nintendo DS, iOS |

| Release | June 1994[1]

|

| Genre(s) | Construction and management sim |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Development took about a year and a half, with the team aiming for as much realism as possible. Certain features, including multiplayer, were dropped. Over 15 million copies were sold, and ports for various games consoles were released, most in 1995. Theme Park received generally positive reviews. Reviewers praised the gameplay and humour, but criticised console ports for reasons such as lack of save or mouse support. The game received a Japanese localisation (in addition to normal Japanese releases), Sim Theme Park, released in 1997 for the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation, and remakes for the Nintendo DS and iOS, released in 2007 and 2011 respectively. Theme Hospital is Bullfrog's thematic successor to the game, and two direct sequels followed: Theme Park World (known as Sim Theme Park in some territories) and Theme Park Inc (also known as SimCoaster).

Gameplay

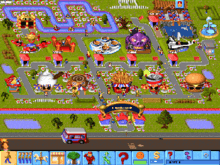

Starting with a free plot of land in the United Kingdom and few hundred thousand pounds, the player must build a profitable amusement park.[2] Money is spent on building rides, shops, and staff,[3] and earned through sale of entry tickets, merchandise, and refreshments.[4] Shops available include those selling foodstuff (such as ice creams) or soft drinks, and games such as coconut shies and arcades.[5] Their attributes can be customised, which may affect customers' behaviour: for example, affecting the flavour of foods (e.g. by altering the amount of sugar an ice cream contains) may affect customers' enticements to return.[6] Facilities such as toilets, and items that enhance the park's scenery (such as trees and fountains) can be purchased.[7] Over thirty attractions, ranging in complexity from the bouncy castle and tree house to more complicated and expensive rides such as the roller coaster and Ferris wheel are available. Also available as rides are shows (called 'acts') with themes such as clowns and mediaeval.[8] Certain rides, such as roller coasters, require a track to be laid out.[9] The ride complement varies between platforms: for example, the PlayStation version is missing the mediaeval and dolphin shows.[10] Rides require regular maintenance: if neglected for too long they will explode.[11] Depending on the platform, it is possible to tour the park or the rides.[12][13]

Visitors arrive and leave via a bus. The entry price can be set, and loans can be taken out.[14] The player starts with a limited number of shops, rides, and facilities available. Research must be carried out to purchase others.[15] Research can also make rides more durable, staff more efficient, and buses larger with increased capacity. The topic of research and how much funding goes into it is determined by the player.[16]

Staff available for employment include entertainers, security guards, mechanics, and handymen.[17] Lack of staff can cause problems, including messy footpaths, rides breaking down, crime, and unhappy visitors.[18] If visitors become unhappy, thugs may come to vandalise the park by committing offences such as popping balloons, stealing food, and beating up entertainers.[19] Occasionally, wages and the price of goods must be negotiated; failure to reach an agreement results in staff strikes or loss of shipment.[20][21]

Theme Park offers three levels of simulation: the higher difficulties requiring more management of aspects such as logistics. For example, at full level, the player must manage research, negotiations, stocks, and shares. On sandbox, the game does not involve those aspects.[22] The player can switch mode at any time.[23] Game time is implemented like a calendar: at the end of each year, the player is judged on that year's performance against rivals. Game speed can be adjusted, and staff can be moved by the player.[24] Cash awards may be earned for doing well, and trophies may be awarded for achievements such as having the longest roller coaster.[25]

The goal is to increase the park's value and available money so that it can be sold and a new lot purchased from another part of the world to start a new theme park.[26] Once enough money has been made, the player can auction the park and move on to newer plots,[27] located worldwide and having different factors affecting gameplay, including the economy, weather, terrain and land value.[28][29] The Mega Drive and SNES versions feature different settings (e.g. desert and glacier) depending on the park's location.[30]

Development

Peter Molyneux stated that he came up with the idea of creating Theme Park because he felt the business genre was worth pursuing.[31] He said that Theme Park is a game he had always wanted to create, and wanted to avoid the mistakes of his earlier business simulation game, The Entrepreneur: he wanted to create a business simulation game and make it fun so that people would want to play it.[32] In an interview, he explained that the primary reason he created Theme Park was because he wanted players to create their dream Theme Park. Another reason is he wanted players to understand the kind of work running one entails. The three difficulty settings enable players to choose the desired depth: simply having fun creating a theme park, or making all the business decisions too. Molyneux stated that the most difficult part to program was the visitors' behaviour.[33]

The story was originally to have the player play the role of a nephew who had inherited a fortune from his aunt, to be spent only on the world's largest and most profitable theme park.[34] The graphics were drawn and modelled using 3D Studio.[34] Molyneux stated that each person takes about 200 bytes of memory, enough for them to have their own personality.[34] The team travelled the world visiting theme parks and taking notes, and sound effects were sampled from real parks. Molyneux explained that they were going for as much realism as possible. There was to be a feature where a microphone is placed on a visitor and so the player could hear what they were saying,[31] and multiplayer support was dropped two weeks prior to release because of a deadline.[35] Multiplayer mode would have let players send thugs to other parks.[36]

Theme Park took roughly a year and a half to develop.[36] Much of the code was used in Theme Hospital, and an animation editor was improved by Theme Hospital's designer and producer Mark Webley, who dubbed it The Complex Engine.[37] Artist Gary Carr did not think the game was a good idea, and disliked the art style. Molyneux wanted him to create a colourful style to appeal to a Japanese market, but Carr disagreed and left Bullfrog. Carr later retracted his beliefs and, in 2012, stated that he considered the game a classic.[38] In 1994, Molyneux was developing both Theme Park and Magic Carpet.[39] The game was mostly complete by January 1994 and scheduled for release on 28 March,[32][40] but this was pushed back to June,[34] and then August.[41] Theme Park sold over 15 million copies,[37] and was extremely popular in Japan (the Japanese PlayStation version sold 85 thousand copies within weeks[42]),[43] as well as Europe.[39] Theme Park did not sell well in the United States; Molyneux hypothesised that this was because the graphics are too childish for American audiences.[39] The game is the first instalment in Bullfrog's Designer Series, and it was intended for the series to use Theme Park's engine and for each instalment to have three simulation levels.[44] The PC version was sponsored by Midland Bank.[45]

The PlayStation port was developed by Krisalis Software, and released in 1995.[46] The Mega CD port features CD soundtrack,[47] and was developed by Domark and released in the same year.[48] Bullfrog developed the Mega Drive port, which was mostly complete by April 1995,[49] and the Sega Saturn port, released in October 1995.[50] Other ports include the Amiga CD32,[51] Atari Jaguar,[52] 3DO Interactive Multiplayer, Super Nintendo Entertainment System,[53] and Macintosh.[54] Mark Healey handled the graphics for the Mega Drive and Super Nintendo Entertainment System versions.[55] The graphics were completed in three days.[55] The PC version was released on gog.com on 9 December 2013.[56]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Theme Park received critical acclaim. The gameplay, graphics, and addictiveness in particular were well received. A reviewer of Edge commented that the game is complex, but praised the detail and addictiveness.[57] PC Gamer's Gary Whitta was highly impressed with the game: he eulogised the fun factor and compared it to that of SimCity 2000. He also praised the "gloriously cartoony" graphics and "exceptional" soundtrack. Theme Park was named as the PC Gamer June 1994 Game of The Month.[11][66] Computer and Video Games's reviewer complimented the "cute" graphics, and described the game as "fun" and "feature-packed".[41] The visitors' and ride animations were complimented by French magazine Joystick.[73]

The Jaguar version was noted by critics as having problems such as slowdown and lack of a save option, although some liked the graphics and gameplay. The four reviewers of Electronic Gaming Monthly commented that the game itself is great fun, but that the Jaguar conversion had confusing menus and dithered text which is excessively difficult to read.[58] GamePro echoed these criticisms and further stated that the Jaguar version suffers from frustrating slowdown. They summarised that "Ocean didn't work hard enough to make Theme Park look and sound good on the Jaguar".[77] A reviewer for Next Generation took the reverse position, saying that the Jaguar conversion "is seamless" and the game itself was mediocre. Their elaboration was that "Slow gameplay and confusing layouts keep it from ever achieving the addictiveness of the other 'god' games, and most players will find themselves bored before they've even run through all of the options".[62] German magazine Atari Inside's reviewer complimented the addictiveness, but the lack of save opportunities was criticised,[72] and a reviewer from ST Computer believed the game's complexity and colourful graphics assured it of being long and attractive.[76] Mega Fun's main criticism of the Jaguar version was its inability to save in-game.[75]

The Saturn version was noted as being mostly faithful to the PC original. Sam Hickman of Sega Saturn Magazine praised it for retaining the original intro, music, speech samples, and features of the PC version (all of which had been left out of most previous console versions),[68] although a reviewer from the Japanese magazine of the same name criticised the lack of mouse support.[71] Electronic Gaming Monthly's reviewer held a similar opinion to that of Hickman by commending the Saturn version for being a comprehensive port of the PC original, and also applauded the addictive simulation gaming of Theme Park, calling it "SimCity with a playful spirit".[59] Mean Machines Sega's reviewer compared it to the Mega Drive version, citing the save function and variety of entertainers as major improvements over that version.[50] A Next Generation critic lauded the game's "simple interface", "infectious gameplay", and "realistic business fundamentals", but felt the Saturn's "near-perfect" conversion of the PC original was commendable but unexciting, and expressed regret that there were no upgrades or additions.[64] GamePro gave a terse joint review of the Saturn and PlayStation versions, commenting, "you decide every detail, right down to the roller coaster's speed. Simple graphics and sounds offer up little treats to keep the game interesting. Overlapping menu systems force you to read the manual".[78]

Critics had similar opinions of other versions. Mean Machines Sega described the game as "the most complex Megadrive game ever created", and eulogised playability and longevity, but criticised the behaviour of the handymen.[70] CU Amiga praised the addictiveness of the Amiga version, and called the game "colourful".[69] The visuals were likewise commended by Jeuxvideo.com on the PC and Macintosh versions, and the British humour was complimented as well.[60][61] German magazine Mega Fun compared the SNES version to the Mega Drive version, and said the SNES version had better controls and music, creating atmosphere.[74] Reviewing the PlayStation version, Maximum said that the game "is probably one of the best sim games around. It manages to strike a balance between in-depth game play and personality, which you don't get with the more brow-furrowing games of this genre", although the only improvement being a view option was cited as a disappointment.[67] Next Generation reviewed the 3DO version of the game, and stated that "It's cute, but we're waiting for 3DO's Transport Tycoon".[63] In their review of the Macintosh version of the game, they believed that players would think of it when they visit Disneyland.[65]

In 1997, Theme Park appeared jointly with Theme Hospital at #61 on PC Gamer's list of top 100 games.[79]

Re-releases

A Japanese remake of Theme Park, titled Shin Theme Park (新テーマパーク, Shin Tēma Pāku, lit. New Theme Park) was released on 11 April 1997 by Electronic Arts Victor for the Sony PlayStation and Sega Saturn.[80][81] This version is different to other releases in Japan; the game's style and visuals are changed.[81] The game was remade for the Nintendo DS by EA Japan. It was released in Japan on 15 March 2007 with releases in the US and Europe on 20 March 2007 and 23 March 2007. New features of the game are the user interface, which was designed to fit the stylus functionality of the DS platform, and bonus rides/shops exclusive to certain properties, such as a tea room themed on an AEC Routemaster bus for England, Japanese dojo-style bouncy castle for Japan, a Coliseum-themed pizza parlour for Italy, a La Sagrada Familia-themed paella restaurant for Spain etc.[82] The remake is based on the DOS version.[26] The game differs from the original in that the game provides four different advisers.[82] Theme Park was remade for iOS in 2011. Items can only be placed on designated places, and the game relies on premium items. Rides can cost up to $60 (£46) in real money, and for this reason the game was not well received.[83][84][85]

See also

References

- "preScreen". Edge. No. 9. Future plc. June 1994. p. 15.

- Super Guide, pp. 14–17.

- Official Guide Book pp. 8–27.

- Perfect Guide, pp. 16,64–67.

- Perfect Guide, p. 24.

- Manual, pp. 43,44.

- Super Guide, pp. 75–78.

- Perfect Guide, pp. 22,23.

- Ultimate Book, p. 44.

- PlayStation Certain Victory Guide, back cover.

- "Theme Park A Beginner's Guide". PC Gamer. No. 9. Bath: Future plc. August 1994. pp. 94–97. ISSN 1470-1693.

- Official Guide Book, pp. 28–36.

- PlayStation Certain Victory Guide, p. 6.

- Perfect Guide, pp. 16,17.

- PlayStation Certain Victory Guide, p. 57.

- Perfect Guide, pp. 18,19.

- Pefect Guide, pp. 73,74.

- Manual, pp. 34,35.

- Manual, p. 37.

- Official Guide Book, p. 108.

- PlayStation Certain Victory Guide, pp. 76,77.

- Manual, p. 11.

- Manual, p. 52.

- "Bullfrog's Guide To Theme Park". MegaDrive Tips. Mean Machines Sega. No. 32. Peterborough: EMAP. June 1995. pp. 54–56. ISSN 0967-9014.

- Perfect Guide, pp. 144,145.

- Tom Magrino (3 April 2007). "Theme Park DS Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Official Guide Book, pp. 82,83.

- Perfect Guide, pp. 26,27.

- Official Guide Book, pp. 43–46.

- "Theme Park" (PDF). Computer and Video Games. No. 161. Peterborough: EMAP. April 1995. pp. 36–37. ISSN 0261-3697. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "Funtime at Bullfrog". Prescreen. Edge. No. 4. Bath: Future plc. January 1994. pp. 37–43. ISSN 1350-1593.

- Gary Whitta (December 1993). "Theme Park Where Wonders Never Cease". Scoop!. PC Gamer. Vol. 1 no. 1. Bath: Future plc. pp. 20–22. ISSN 1470-1693.

- Ultimate Book, p. 140.

- "Theme Park". Prescreen. Edge. No. 9. Bath: Future plc. June 1994. pp. 34–35. ISSN 1350-1593.

- Geoff Keighley. "The Final Hours of Black & White". GameSpot. p. 19. Archived from the original on 21 November 2001. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- "Theme Park". Computer and Video Games. No. 151. Peterborough: EMAP. June 1994. pp. 28–31. ISSN 0261-3697.

- "The Making of Theme Hospital". Retro Gamer. No. 130. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. June 2014. pp. 46–51. ISSN 1742-3155.

- "Revisiting Bullfrog: 25 Years On". Retro Gamer. No. 110. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. December 2012. pp. 60–67. ISSN 1742-3155.

- Ron Dulin. "GameSpot Presents Legends Of Game Design: Peter Molyneux". GameSpot. GameSpot. p. 7. Archived from the original on 26 February 2003. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "The illustrious PC Gamer Top 20 of 1994". PC Gamer. No. 2. Bath: Future plc. January 1994. p. 49. ISSN 1470-1693.

- "Theme Park". Computer and Video Games. No. 153. Peterborough: EMAP. August 1994. pp. 54–55. ISSN 0261-3697.

- "Console Crazy". Bullfrog Bulletin. No. 3. Guildford: Bullfrog Productions. 1996. pp. 18–19.

- "Theme Park". Saturn Preview. Mean Machines Sega. No. 36. Peterborough: EMAP. October 1995. pp. 42–43. ISSN 0967-9014.

- "Bullfrog makes designs". PC Gamer. Vol. 1 no. 7. Bath: Future plc. June 1994. p. 24. ISSN 1470-1693.

- Manual, back cover

- Theme Park PlayStation Manual (PAL ed.). Electronic Arts. 1995. p. 47.

- Theme Park Mega CD box. 1995. p. back.

- Theme Park Mega CD manual. 1995. p. 31.

- "Theme Park". MegaDrive Preview. Mean Machines Sega. No. 30. Peterborough: EMAP. April 1995. pp. 36–37. ISSN 0967-9014.

- "Saturn Review: Theme Park" (PDF). Mean Machines Sega. No. 37. Peterborough: EMAP. November 1995. pp. 66–68. ISSN 0967-9014.

- "Theme Park - Amiga CD32". IGN. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "Theme Park - Jaguar". IGN. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "Theme Park - Super NES". IGN. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "Theme Park - Macintosh". IGN. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "In The Chair With Mark Healey". Retro Gamer. No. 139. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. pp. 92–97. ISSN 1742-3155.

- "Release: Theme Park". gog.com. 9 December 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- "Theme Park". Testscreen. Edge. No. 11. Bath: Future plc. August 1994. pp. 54–55. ISSN 1350-1593.

- "Review Crew: Theme Park". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 69. Ziff Davis. April 1995. p. 40. ISSN 1058-918X.

- "Review Crew: Theme Park". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 78. Ziff Davis. January 1996. p. 40. ISSN 1058-918X.

- "Test du jeu Theme Park sur PC". Jeuxvideo.com (in French). 9 December 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "Test du jeu Theme Park sur Mac". Jeuxvideo.com (in French). 9 December 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "Theme Park". Next Generation. No. 4. Imagine Media. April 1995. pp. 89–90. ISSN 1078-9693.

- "Finals". Next Generation. No. 5. Imagine Media. May 1995. p. 89.

- "Theme Park". Next Generation. No. 13. Imagine Media. January 1996. p. 156. ISSN 1078-9693.

- "Finals". Next Generation. No. 8. Imagine Media. August 1995. p. 75.

- Gary Whitta (June 1994). "Theme Park". PC Gamer. Vol. 1 no. 7. Bath: Future plc. pp. 56–57. ISSN 1470-1693.

- "Maximum Reviews: Theme Park". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine. No. 2. EMAP. November 1995. p. 153. ISSN 1360-3167.

- Hickman, Sam (November 1995). "Review: Theme Park" (PDF). Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 1. Peterborough: EMAP. pp. 64–65. ISSN 1360-9424. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "Theme Park". CU Amiga. No. 55. EMAP. September 1994. pp. 70–71. ISSN 0963-0090. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "MegaDrive Review: Theme Park" (PDF). Mean Machines Sega. No. 31. Peterborough: EMAP. May 1995. pp. 18–25. ISSN 0967-9014. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "テーマパーク" (PDF). Sega Saturn Magazine (in Japanese). Tokyo: SoftBank Publishing. December 1995. p. 204.

- "Jaguar-Software: Theme-Park". Atari Inside (in German). April 1995. ISSN 1437-3580. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "Theme Park". Joystick (in French). No. 53. October 1994. p. 78. ISSN 0994-4559.

- "Theme Park". Mega Fun (in German). July 1995. p. 70. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "Theme Park". Mega Fun (in German). May 1995. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "Theme Park – Wirtschaftssimulation mal anders". ST Computer (in German). May 1995. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "ProReview: Theme Park". GamePro. No. 68. IDG. March 1995. p. 104. ISSN 1042-8658.

- "Quick Hits: Theme Park". GamePro. No. 90. IDG. March 1996. p. 75. ISSN 1042-8658.

- "The PC Gamer Top 100". PC Gamer. No. 45. Bath: Future plc. July 1997. p. 61. ISSN 1470-1693.

- "新テーマパーク". playstation.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "新テーマパーク" (PDF). Sega Saturn Magazine (in Japanese). Tokyo: Softbank Publishing. April 1997. p. 138. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Mike Jackson (1 February 2007). "Interview: EA Japan on its promising DS remake". computerandvideogames. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Talor Berthelson (8 December 2011). "Theme Park Review". Gamezebo. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Dan Crawley (5 December 2011). "EA continues to target freemium market – offering $60 rides on Theme Park iOS game". venturebeat. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- "Theme Park on iOS is an expensive, slow-moving experience". Aol. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

Sources

- テーマパークスーパガイド [Theme Park Super Guide]. Popcom Books (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 10 September 1995. ISBN 978-4-09-385070-4.

- 公式テーマパーク攻略ガイドブック [Official Theme Park Strategy Guide Book]. Login Books (in Japanese). Tokyo: Aspect. 30 September 1995. ISBN 978-4-89366-407-5.

- テーマパークパーフェクトガイド [Theme Park Perfect Guide] (in Japanese). Tokyo: SoftBank Books. 25 July 1995. ISBN 978-4-89052-723-6.

- テーマパーク プレイステーション必勝攻略スペシャル [Theme Park PlayStation Certain Victory Guide Special] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Keibunsha. 1996. ISBN 978-4-7669-2435-0.

- テーマパーク究極本 (BESTゲーム攻略SERIES) [Theme Park Ultimate Book (Best Game Strategy Guide Series)] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Mikio Kurihara. 15 February 1996. ISBN 978-4-584-16034-3.

- Bullfrog (1994). Theme Park Manual (PC ed.). Slough: Electronic Arts.