The Trojan Women

The Trojan Women (Ancient Greek: Τρῳάδες, Trōiades), also translated as The Women of Troy, and also known by its transliterated Greek title Troades, is a tragedy by the Greek playwright Euripides. Produced in 415 BC during the Peloponnesian War, it is often considered a commentary on the capture of the Aegean island of Melos and the subsequent slaughter and subjugation of its populace by the Athenians earlier that year (see History of Milos).[1] 415 BC was also the year of the scandalous desecration of the hermai and the Athenians' second expedition to Sicily, events which may also have influenced the author.

| The Trojan Women | |

|---|---|

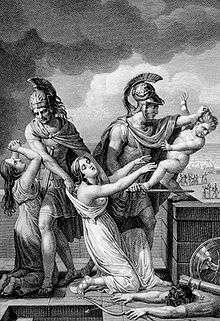

An engraving of the death of Astyanax | |

| Written by | Euripides |

| Chorus | Trojan women |

| Characters | Hecuba Cassandra Andromache Talthybius Menelaus Helen Poseidon Athena |

| Place premiered | Athens |

| Original language | Ancient Greek |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Setting | Near the walls of Troy |

The Trojan Women was the third tragedy of a trilogy dealing with the Trojan War. The first tragedy, Alexandros, was about the recognition of the Trojan prince Paris who had been abandoned in infancy by his parents and rediscovered in adulthood. The second tragedy, Palamedes, dealt with Greek mistreatment of their fellow Greek Palamedes. This trilogy was presented at the Dionysia along with the comedic satyr play Sisyphos. The plots of this trilogy were not connected in the way that Aeschylus' Oresteia was connected. Euripides did not favor such connected trilogies.

Euripides won second prize at the City Dionysia for his effort, losing to the obscure tragedian Xenocles.[2]

The four Trojan women of the play are the same that appear in the final book of the Iliad lamenting over the corpse of Hector. Taking place near the same time is Hecuba, another play by Euripides.

Plot

Hecuba: Alas! Alas! Alas! Ilion is ablaze; the fire consumes the citadel, the roofs of our city, the tops of the walls!

Chorus: Like smoke blown to heaven on the wings of the wind, our country, our conquered country, perishes. Its palaces are overrun by the fierce flames and the murderous spear.

Hecuba: O land that reared my children!

Euripides's play follows the fates of the women of Troy after their city has been sacked, their husbands killed, and as their remaining families are about to be taken away as slaves. However, it begins first with the gods Athena and Poseidon discussing ways to punish the Greek armies because they condoned that Ajax the Lesser raped Cassandra, the eldest daughter of King Priam and Queen Hecuba, after dragging her from a statue of Athena. What follows shows how much the Trojan women have suffered as their grief is compounded when the Greeks dole out additional deaths and divide their shares of women.

The Greek herald Talthybius arrives to tell the dethroned queen Hecuba what will befall her and her children. Hecuba will be taken away with the Greek general Odysseus, and Cassandra is destined to become the conquering general Agamemnon's concubine.

Cassandra, who can see the future, is morbidly delighted by this news: she sees that when they arrive in Argos, her new master's embittered wife Clytemnestra will kill both her and her new master. She sings a wedding song for herself and Agamemnon that describes their bloody deaths. However, Cassandra is also cursed so that her visions of the future are never believed, and she is carried off.

The widowed princess Andromache arrives and Hecuba learns from her that her youngest daughter, Polyxena, has been killed as a sacrifice at the tomb of the Greek warrior Achilles.

Andromache's lot is to be the concubine of Achilles' son Neoptolemus, and more horrible news for the royal family is yet to come: Talthybius reluctantly informs her that her baby son, Astyanax, has been condemned to die. The Greek leaders are afraid that the boy will grow up to avenge his father Hector, and rather than take this chance, they plan to throw him off from the battlements of Troy to his death.

Helen is supposed to suffer greatly as well: Menelaus arrives to take her back to Greece with him where a death sentence awaits her. Helen begs and tries to seduce her husband into sparing her life. Menelaus remains resolved to kill her, but the audience watching the play knows that he will let her live and take her back. At the end of the play it is revealed that she is still alive; moreover, the audience knows from Telemachus' visit to Sparta in Homer's Odyssey that Menelaus continued to live with Helen as his wife after the Trojan War.

In the end, Talthybius returns, carrying with him the body of little Astyanax on Hector's shield. Andromache's wish had been to bury her child herself, performing the proper rituals according to Trojan ways, but her ship had already departed. Talthybius gives the corpse to Hecuba, who prepares the body of her grandson for burial before they are finally taken off with Odysseus.

Throughout the play, many of the Trojan women lament the loss of the land that reared them. Hecuba in particular lets it be known that Troy had been her home for her entire life, only to see herself as an old grandmother watching the burning of Troy, the death of her husband, her children, and her grandchildren before she will be taken as a slave to Odysseus.

Modern Treatments and Adaptations

In 1974, Ellen Stewart, founder of La MaMa Experimental Theater Club in New York, presented "The Trojan Women" as the last Fragment of a Trilogy (including Medea and Electra). With staging by Romanian-born theater director Andrei Serban and music by American composer Elizabeth Swados, this production of The Trojan Women went on to tour more than thirty countries over the course of forty years. Since 2014, The Trojan Women Project has been sharing this production with diverse communities that now include Guatemala, Cambodia and Kosovo. A Festival of work from all participants is scheduled for December, 2019.

The French public intellectual, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a version of The Trojan Women that mostly is faithful to the original Greek text, yet includes veiled references to European imperialism in Asia, and emphases of existentialist themes. The Israeli playwright Hanoch Levin also wrote his own version of the play, adding more disturbing scenes and scatological details.

A 1905 stage version, translated by Gilbert Murray, starred Gertrude Kingston as Helen and Ada Ferrar as Athena at the Royal Court Theatre in London.[3]

The Mexican film Las Troyanas (1963) directed by Sergio Véjar, adapted by writer Miguel Angel Garibay and Véjar, is faithful to the Greek text and setting; Ofelia Guilmain portrays Hecuba, the black&white photography is by Agustín Jimenez.

Cypriot-Greek director Mihalis Kakogiannis used Euripides' play (in the famous Edith Hamilton translation) as the basis for his 1971 film The Trojan Women. The movie starred American actress Katharine Hepburn as Hecuba, British actors Vanessa Redgrave and Brian Blessed as Andromache and Talthybius, French-Canadian actress Geneviève Bujold as Cassandra, Greek actress Irene Papas as Helen, and Patrick Magee, an actor born in Northern Ireland, as Menelaus.

David Stuttard’s 2001 adaptation, Trojan Women,[4] written in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, has toured widely within the UK and been staged internationally. In an attempt to reposition The Trojan Women as the third play of a trilogy, Stuttard then reconstructed Euripides’ lost Alexandros and Palamedes (in 2005 and 2006 respectively), to form a 'Trojan Trilogy', which was performed in readings at the British Museum and Tristan Bates Theatre (2007), and Europe House, Smith Square (2012), London. He has also written a version of the satyr play Sisyphus (2008), which rounded off Euripides’ original trilogy.[5][6]

Femi Osofisan's 2004 play Women of Owu sets the story in 1821, after the conquest of the Owu kingdom by a coalition of other West African states. Although it is set in 19th century Africa, Osofisan has said that the play was also inspired by the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the U.S. led coalition.[7]

Another movie based on the play came out in 2004, directed by Brad Mays.[8][9] The production was actually a documentary film of the stage production Mays directed for the ARK Theatre Company in 2003. In anticipation of his soon-to-come multimedia production of A Clockwork Orange, Mays utilized a marginal multimedia approach to the play, opening the piece with a faux CNN report intended to echo the then-current war in Iraq.

Charles L. Mee adapted The Trojan Women in 1994 to have a more modern, updated outlook on war. He included original interviews with Holocaust and Hiroshima survivors. His play is called Trojan Women: A Love Story.

The Women of Troy, directed by Katie Mitchell, was performed at the National Theatre in London in 2007/08. The cast included Kate Duchêne as Hecuba, Sinead Matthews as Cassandra and Anastasia Hille as Andromache.

The Trojan Women, directed by Marti Maraden, was performed at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival at the Tom Patterson Theatre in Stratford, Ontario, Canada, from May 14 to October 5, 2008 with Canadian actress Martha Henry as Hecuba.

Sheri Tepper wove The Trojan Women into her feminist science fiction novel The Gate to Women's Country.

Christine Evans reworks and modernizes the Trojan Women story in her 2009 play Trojan Barbie. Trojan Barbie is a postmodern updating, which blends the modern and ancient worlds, as contemporary London doll repair shop owner Lotte is pulled into a Trojan women's prison camp that is located in both ancient Troy and the modern Middle East.[10]

In 2016, Zoe Lafferty's version of the play, Queens of Syria, in Arabic with English subtitles, was put on by the Young Vic before touring Britain.[11]

Translations

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Translator | Year | Style | Full text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edward Philip Coleridge | 1891 | Prose | Wikisource, |

| Gilbert Murray | 1911 | Verse | |

| Edith Hamilton | 1937 | Verse | |

| Richmond Lattimore | 1947 | Verse | available for digital loan |

| Isabelle K. Raubitschek and Anthony E. Raubitschek | 1954 | Prose | |

| Philip Vellacott | 1954 | Prose and verse | |

| Gwendolyn MacEwen | 1981 | Prose | Gwendolyn MacEwen#cite note-jrank-8 |

| Shirley A. Barlow | 1986 | Prose | |

| David Kovacs | 1999 | Prose | |

| James Morwood | 2000 | Prose | |

| Howard Rubenstein | 2002 | Verse | |

| Ellen McLaughlin | 2005 | Prose | |

| George Theodoridis | 2008 | Prose | |

| Alan Shapiro | 2009 | Prose | |

| Emily Wilson | 2016 | Verse |

See also

Notes

- See Croally 2007.

- Claudius Aelianus: Varia Historia 2.8. (page may cause problems with Internet Explorer)

- MacCarthy, Desmond The Court Theatre, 1904-1907; a Commentary and Criticism

- Stuttard, David, An Introduction to Trojan Women (Brighton 2005)

- open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays/Practitioners/issue1/stuttard.pdf

- davidstuttard.com/Trojan_Trilogy.html

- Osofisan, Femi (2006). Women of Owu. Ibadan, Nigeria: University Press PLC. p. vii. ISBN 9780690263.

- Troy: From Homer's Iliad to Hollywood Epic, by Martin M. Winkler, 2007, Blackwell Publishing

- Photo gallery and video from the Brad Mays stage play based on Philip Vellacott's translation

- ""Trojan Barbie: A Car-Crash Encounter with Euripides' 'Trojan Women'" by newest faculty member Christine Evans". Department of Performing Arts. Georgetown University. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Masters, Tim (6 July 2016). "Queens of Syria gives modern twist to ancient tale". BBC. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

References

- Croally, Neil (2007). Euripidean Polemic: The Trojan Women and the Function of Tragedy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-04112-0

Additional resources

- Mortal Women of the Trojan War, information on each of the Trojan women

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

External links