The Propylaeum

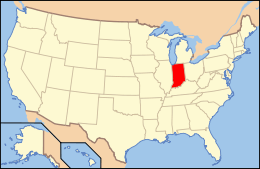

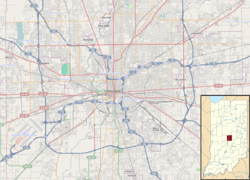

The Propylaeum, also known as the John W. Schmidt House or as the Schmidt-Schaf House, is a historic home and carriage house located at 1410 North Delaware Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The Propylaeum was named after the Greek word "propýlaion," meaning "gateway to higher culture." The property became the headquarters for the Indianapolis Woman's Club in 1923, as well as the host for several other social and cultural organizations. It was initially built in 1890-1891 as a private residence for John William Schmidt, president of the Indianapolis Brewing Company, and his family. Joseph C. Schaf, president of the American Brewing Company of Indianapolis, and his family were subsequent owners of the home.

The Propylaeum (John W. Schmidt House) | |

The Propylaeum, November 2010 | |

| |

| Location | 1410 N. Delaware St., Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°47′11″N 86°9′16″W |

| Area | 1.2 acres (0.49 ha) |

| Architectural style | Tudor Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000039[1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 19, 1973 |

The Indianapolis Propylaeum association, formed in 1888 as a joint stock company of women, continues to manage the site as a gathering place and rental facility for cultural activities and private events. The three-story, Neo-Jacobean-style building is constructed of red brick with limestone trim. It sits on a full basement and has hipped roof of slate with several gables. The main features of its exterior include a wraparound verandah, square tower, and porte-cochère. The property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as "The Propylaeum (John W. Schmidt House)" in 1973. The Indiana Historical Bureau erected a state historical marker at the site in 1999.

History

Propylaeum association

In 1888 May Wright Sewall, an Indianapolis educator, clubwoman, community leader and women's rights advocate, urged members of the Indianapolis Woman's Club (established in 1875) to form a stock company to finance construction of a headquarters building for the club. The women also planned to make earn money for their group by renting the building to the city's other cultural and social organizations.[2][3][4] Sewall later acknowledged that the idea was inspired by building projects that women in other cities had funded, such as the Athenaeum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; the Ladies' Library Association building in Kalamazoo, Michigan; and the Woman's Club of Grand Rapids, Michigan.[4]

The Indianapolis Propylaeum association, named after the Greek word "propýlaion," meaning "gateway to higher culture," incorporated in June 1888, with Sewall elected as its president. Later that month the association issued its initial public offering of $15,000, sold at $25 per share. Stock ownership was restricted to women.[5][6] In May 1889 the Propylaeum's stockholders agreed to increase its capital stock to $20,000. All of the stock was sold by March 10, 1890.[7]

The group laid the cornerstone for the original Propylaeum building at 17 East North Street, between Meridian and Pennsylvania Streets, on May 8, 1890; it was dedicated on January 27, 1891.[8] The Indianapolis Propylaeum was among the first of its kind in the United States to be "financed entirely by women stockholders."[9] From its inception the association intended to offer "educational opportunities"[9] to men and women and establish its clubhouse as a cultural center for the city.[4]

The building served as the headquarters for the Indianapolis Woman's Club, as well as host to several other social and cultural organizations, including music, dramatic, and literary clubs, the Portfolio Club (a group for artists and writers), the Art Association of Indianapolis, and the Contemporary Club, among others.[10][11] In 1892 the Propylaeum association established the Indianapolis Local Council of Women, which changed its name to the Indianapolis Council of Women in 1923. The council advocated woman's suffrage and Progressive-era reforms, such as better streets and sanitary conditions, new laws protecting working conditions for women and girls, and improvements in education and public health. The council's first meeting was held at the Propylaeum building on North Street on May 3, 1892.[9]

In 1923 the Indianapolis city government purchased the Propylaeum's North Street property as part of the site for the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza and had the original Propylaeum building demolished. Instead of constructing a new clubhouse, the association purchased property at Fourteenth and Delaware Streets that included an existing residence, carriage house, and stable. The Propylaeum organization has managed the North Delaware Street site since 1923. It continues to support local cultural activities and sponsors public events. The association also rents its clubhouse for private events.[9][11]

Propylaeum building

The Propylaeum building, also known as the Schmidt-Schaf House, is located at 1410 North Delaware Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. It was built in 1890–91[9] as a private residence for its original owner, John William Schmidt, his wife, Lily, and their four children. John Schmidt was president of the Indianapolis Brewing Company and later the Polar Ice Company. The Schmidt family lived in the home for twelve years. Muncie, Indiana, industrialist George F. McCulloch, owner of the Indianapolis Star, sold it to Joseph C. Schaf in 1905.[12][13] Schaf, who was president of the American Brewing Company of Indianapolis, remodeled the home and lived in it with his wife, Josephine, and their two children. Their daughter, Alice, was married in the home.[11][14]:2–3 [15] The College of Music and Fine Arts acquired the property from Schaf in 1921, but was unable to make payments on it. The college sold the Schmidt-Schaf home to the Propylaeum association, the property's current owner, in 1923. The Propylaeum's tea room opened in September 1924 and remains in operation.[13][16][17]

The property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[1] In 1988 the Propylaeum was used as a set for a few scenes in the moving picture, Eight Men Out (1988), although the home's interiors were significantly altered during filming.[13] The Indiana Historical Bureau erected a state historical marker at the site in 1999.[9]

Building description

Former director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art and art historian Wilbur Peat described the building's architecture as a Neo-Jacobean style, which is characterized by an irregular-shaped floor plan, projecting wall sections and bays, a hipped roof, expansive veranda, multiple gables, and prominent chimneys. The architecture of medieval England, especially Tudor- and Jacobean-style homes in England and elsewhere in Europe have influenced this style.[18] The Propylaeum also has elements of Romanesque Revival, Georgian, and Queen Anne architecture styles.[13]

The three-story, red-brick building with limestone trim sits on a full basement and has a hipped roof of slate and decorative terracotta panels on its gables. Main features of its exterior include a wraparound verandah with limestone columns, a square tower on its north facade, and a porte-cochère on its south side. The interior has large reception rooms on the first floor, a grand staircase, and Rookwood Pottery tiles on its fireplaces. The second floor contains bedrooms and bathrooms; the third floor includes former servants' quarters and a ballroom. The property also has a separate carriage house.[19]

Notes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 1137. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 302–04. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Ray E. Boomhower (2007). Fighting for Equality: A Life of May Wright Sewall. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-87195-253-0.

- Boomhower, pp. 59–61.

- Anne P. Robinson (2008). Every Way Possible: 125 Years of the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Indianapolis, IN: Indianapolis Museum of Art. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-936260-85-3.

- Boomhower, p. 61.

- Boomhower, pp. 61–63.

- "Indianapolis Propylaeum". Indiana Historical Bureau. 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- Boomhower, pp. 60 and 63.

- "Historical Sketch" in "Indianapolis Propylaeum Records, 1888–1997, Collection Guide" (pdf). Indiana Historical Society. January 25, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 98.

- Kathleen Van Nuys (February 29, 1988). "100 Years for the Propylaeum". Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, Indiana. pp. A-10.

- "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved 2016-08-01. Note: This includes Dorothy G. Helmer (May 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: The Propylaeum (John W. Schmidt House)" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-01. and Accompanying photographs

- Wilbur D. Peat (1962). Indiana Houses of the Nineteenth Century. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. plate 175.

- Caroline Dunn (1938). Indianapolis Propylaeum. p. 40. OCLC 7756647.

- "History of the Propylaeum]". Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- Peat, pp. 149–50.

- Helmer, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: The Propylaeum (John W. Schmidt House),” pp. 2–3.

References

- Bodenhamer, David J., and Robert G. Barrows, eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Boomhower, Ray E. (2007). Fighting for Equality: A Life of May Wright Sewall. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87195-253-0.

- Dunn, Caroline (1938). Indianapolis Propylaeum. OCLC 7756647.

- Gugin, Linda C., and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 302–04. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Helmer, Dorothy G. (May 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: The Propylaeum (John W. Schmidt House)" (pdf). Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- "Historical Sketch" in "Indianapolis Propylaeum Records, 1888–1997, Collection Guide" (pdf). Indiana Historical Society. January 25, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- "Indianapolis Propylaeum". Indiana Historical Bureau. 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- Peat, Wilbur D. (1962). Indiana Houses of the Nineteenth Century. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society.

- Robinson, Anne P. (2008). Every Way Possible: 125 Years of the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indianapolis Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-936260-85-3.

- Van Nuys, Kathleen (February 29, 1988). "100 Years for the Propylaeum". Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, Indiana. pp. A-10.