The Man That Was Used Up

"The Man That Was Used Up", sometimes subtitled "A Tale of the Late Bugaboo and Kickapoo Campaign", is a short story and satire by Edgar Allan Poe. It was first published in 1839 in Burton's Gentleman's Magazine.

| "The Man That Was Used Up" | |

|---|---|

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Satirical short story |

| Published in | Burton's Gentleman's Magazine |

| Media type | Print (Periodical) |

| Publication date | 1839 |

The story follows an unnamed narrator who seeks out the famous war hero John A. B. C. Smith. He becomes suspicious that Smith has some deep secret when others refuse to describe him, instead remarking only on the latest advancements in technology. When he finally meets Smith, the man must first be assembled piece by piece. It is likely that in this satire Poe is actually referring to General Winfield Scott, veteran of the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Additionally, some scholars suggest that Poe is questioning the strong male identity as well as how humanity falls as machines become more advanced.

Plot summary

An unnamed narrator meets the famous Brevet Brigadier General John A. B. C. Smith, "one of the most remarkable men of the age" and a hero of "the late tremendous swamp-fight, away down South, with the Bugaboo and Kickapoo Indians." Smith is an impressive physical specimen at six feet tall with flowing black hair, "large and lustrous" eyes, powerful-looking shoulders, and other essentially perfect attributes. He is also known for his great speaking ability, often boasting of his triumphs and about the advancements of the age.

The narrator wants to learn more about this heroic man. He finds that people do not seem to want to speak about the General when asked, only commenting on achievements of the "wonderfully inventive age" and how "horrid" the Native Americans whom the General had fought against had been. The narrator begins to believe there is some concealed secret he must uncover.

When he visits the General's home, he sees nothing but a strange bundle of items on the floor. The bundle, however, begins to speak. It is the General himself, and his servant begins to "assemble" him, piece by piece. Limbs are screwed on, a wig, glass eye and false teeth, and a tongue, until the man himself stands "whole". The General has lost more than battles, it seems: he was captured and severely mutilated by Native American warriors and now much of his body is composed of prostheses, which must be put in or on every morning and without which he cannot appear in public. The narrator now understands the General's secret — he "was the man that was used up."

Publication history

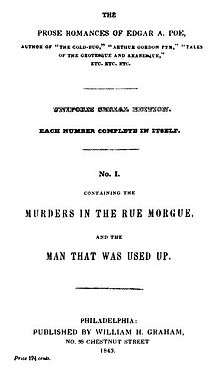

The story was first published in Burton's Gentleman's Magazine in August 1839[1] and collected in Poe's 1840 anthology Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque. In 1843, Poe had the idea to print a series of pamphlets with his stories, though he printed only one: "The Man That Was Used Up" paired with "The Murders in the Rue Morgue". It sold for 12 and a half cents.[2]

Analysis

Critics have identified John A. B. C. Smith as representing General Winfield Scott, one of the longest-serving generals in American history who had commanded forces in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War.[3] Scott was actually a close relative of the second wife of Poe's foster father John Allan. Scott had been injured in the Seminole and Creek Indian removal campaigns and would later run for President of the United States as a Whig candidate.[4] Scott also served in the Black Hawk War, in which a number of Kickapoo Indians participated. At the time Poe wrote the tale in 1839, Scott was already considered a possible Whig candidate for the presidency, though he would lose the election in 1852.[5] Alternatively, it has been suggested that Poe may have been referring to Richard Mentor Johnson, Vice President of the United States under Martin Van Buren.[6]

According to scholar Leland S. Person, Poe is using the story as a critique of male military identity, which he knew well from his own military career and his studies at the United States Military Academy at West Point. It is a literal deconstruction of the identity of a military model of manhood that was given status after Indian removal campaigns of the 1830s. The story seems to suggest that the war hero has nothing left but the injuries he has received in battle to make up his identity.[7] According to Shawn James Rosenheim, Poe also is questioning technology, suggesting that it will soon be difficult to distinguish man from machine.[8] The story also has minor critiques of racism; the war hero was taken apart by Indians but is put together by his "old negro valet" named Pompey (a name Poe also uses in "A Predicament"), arguably undermining the power of white male dominance.[7] Poe may also have been reacting to the popular "subversive" humor of the day, exaggerating the technique to the point of being inane.[9]

The opening epigraph to the story is from Le Cid by Pierre Corneille and translates to:

- "Weep, weep, my eyes and float yourself in tears!

- The better half of my life has laid the other to rest."[3]

The story bears a resemblance to "A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed", a satiric poem by Jonathan Swift from 1731. Both works depict grotesquely artificial bodies: Swift's poem features a young woman preparing for bed by deconstructing, while Poe's story features an old man reconstructing himself to begin his day.[4]

References

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998: 283. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- Ostram, John Ward. "Poe's Literary Labors and Rewards" in Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987: 40.

- Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001: 148. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X

- Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1992: 111. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972: 193. ISBN 0-8071-2321-8

- Mooney, Stephen L. "The Comic in Poe's Fiction" in On Poe: The Best from "American Literature". Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993: 137. ISBN 0-8223-1311-1

- Person, Leland S. "Poe and Nineteenth Century Gender Constructions" as collected in A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe, J. Gerald Kennedy, ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001: 157. ISBN 0-19-512150-3

- Rosenheim, Shawn James. The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997: 101. ISBN 978-0-8018-5332-6

- Reynolds, David S. Beneath the American Renaissance: The Subversive Imagination in the Age of Emerson and Melville. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1988: 527. ISBN 0-674-06565-4

External links