The Cradock Four

The Cradock Four were a group of four anti-apartheid activists who were abducted and murdered by South African security police in June 1985, named as such as all four were from the town of Cradock, Eastern Cape. The South African apartheid government denied that they had ordered the killings, but a document leaked to the press resulted in the removal of several police officers. After three inquests, a judge ruled that the security forces had been involved, but none of the officers were ever charged with or convicted of the murders.

On 27 June 1985, Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli, were detained by the security police outside Port Elizabeth. Goniwe and Calata were rumoured to be on a secret police hit list for their active participation in the struggle against apartheid in the Cradock area. The South African security police murdered them and burned their bodies.[1]

Members of The Cradock Four

Matthew Goniwe was a teacher and popular community leader and organiser in Cradock. Goniwe was arrested in June 1976 in Mthatha for four years under the Suppression of Communism Act for reading communist books. He returned to Cradock in 1981 and became a teacher at Sam Xhallie Secondary School in 1983. He was also instrumental in the formation of the Cradock Residents Association (CRADORA) and Cradock Youth Association (CRADOYA) in 1983. The organisations successfully managed to get the apartheid government to lower rents in Cradock in May 1983. Goniwe was also the rural organiser of the United Democratic Front (UDF) and was responsible for the formation of street committees in Cradock, Adelaide, Kirkwood Noupoort and Kenton-on-Sea.[2]

Fort Calata was a school teacher at Sam Xhallie Secondary School and a close political ally of Goniwe. In October 1980, he was detained in Dimbaza for three weeks for writing a letter to the municipality informing them about the dirty streets and the unhygienic bucket system. He was later transferred to Cradock where he, alongside Goniwe, formed both CRADORA and CRADOYA in 1983. Calata was also an active member of the United Democratic Front.[3]

Sicelo Mhlauli, a close friend of Goniwe, with whom he had grown up with in Cradock, was a school principal in Oudtshoorn. Mhlauli had begun his career as a teacher at Tembalabantu High School in Zwelitsha in the 1970. However, harassment by the Ciskei government drove him to Archie Velile School. He was arrested by the Ciskei government after taking schoolkids to a hospital after they were wounded after a riot. Mhlauli relocated to Oudtshoorn, where he began teaching in 1982 until he became the principal. He was active in the Oudtshoorn Youth Organisation and a community newspaper- Saamstaan. Mhlauli also became an active member of the UDF and attended its launch in 1983. He survived an arson attack in which his office and personal belongings were destroyed that same year.[4]

Sparrow Mkhonto was a railway worker who was instrumental in the formation of CRADORA and CRADOYA and the successful lowering of the rents in Cradock. Mkhonto became a senior office bearer of CRADORA. His involvement with CRADORA caused the Security Police to conspire with his employers at the railway to have him dismissed on a spurious charge.[5]

Background

In 1983, the Cradock Youth Association (CRADOYA) was launched with Goniwe being elected as its first chairperson and Fort Calata, as its secretary. The civil movement's first move was to fight against the unfair rental system being proposed by the East Cape Administration Board. In May 1983, Goniwe called a mass meeting to discuss how the community should respond to high rents, and the Cradock Residents’ Association (CRADORA) was formed. After applying sufficient pressure, CRADORA won the fight as rents were lowered. After the launch of the United Democratic Front (UDF) on 20 August 1983, CRADORA became affiliated to it.[2]

The apartheid government's Security Police instructed the Department of Education (DET) to transfer Goniwe out of Cradock on 18 October 1983. Goniwe was offered a position as principal in Graaff-Reinet, but declined. He applied to become an ordinary teacher at a school in Cradock, but this was turned down. The DET sent Goniwe a telegram on 29 November 1983, informing him of his transfer to Graaff-Reinet from 1 January 1984. A CRADOYA meeting attended by about 2 000 people from the community encouraged Goniwe not to accept the offer. When Goniwe did not report for work in Graaf-Reinet the following year, the DET told him he had “dismissed himself” and he was officially fired on 27 January 1984.[2] This led to a school boycott which started on 3 February in Cradock and spread to the surrounding areas. By 11 March 1984, 4 236 pupils had joined the boycott which lasted for 15 months.[2]

Goniwe's position in the UDF grew as he was appointed rural organiser on 6 March 1984. The political relationship between Calata and Goniwe led the security police to seek a way to silence or eliminate them. Goniwe was placed under surveillance by the Cradock security police chief Major Eric Winter. His phone was tapped and a tamatie (electronic listening device) was planted in his house. On 23 March, 1984 the local magistrate banned all CRADORA and CRADOYA meetings. This sparked unrest as the community responded by throwing stones. However, the police suppressed the riot quickly. Former Finance Minister Barend du Plessis proposed the “removal” of Goniwe and Calata at a State Security Council (SSC) meeting on 19 March 1984: Referring to Goniwe and Calata, du Plessis stated that "In Cradock is daar twee oud-onderwysers wat as agitators optree. Dit sou goed wees as hulle verwyder kon word.” (In Cradock there are two ex-teachers who are acting at agitators. It would be good if they could be removed.)[3]

On 31 March 1984, at 10 o'clock in the evening the police arrested and detained Calata, Goniwe and his cousin Mbulelo Goniwe. Fezile Donald Madoda Jacobs, a headboy at Lingelihle High School and a COSAS and CRADOYA leader, had been detained two days before. On 31 March the Minister of Law and Order Louis le Grange banned all meetings for three months.[3] Tensions escalated and riots broke out with petrol bombings and stoning of houses of community councillors. Boycott-related violence erupted on 15 April, when students marched through the township of Lingelihle demanding the reinstatement of Goniwe. On 27 May, police and the South African Defence Force (SADF) cordoned off Lingelihle township searching for public violence suspects. In June 1984, Goniwe, his nephew Mbulelo, Calata and Jacobs who were still in detention were listed as a potential threat under the Internal Security Act. During their detention, Calata’s wife, Nomonde suffered harassment from the security police and she was threatened with eviction from their home. The little shop that she had set up to support the family was vandalised.[3]

After the police teargassed the township on 15 June, the community began a boycott of white-owned shops for one day on the anniversary of the Soweto uprising, June 16. The police dispersed the crowd with sjamboks and teargas, and police vehicles were stoned. More than 200 people were charged with arson and unlawful gathering. In August, a successful seven-day boycott of white shops was called to protest against the detentions of their leaders. The detained men were released on 10 October 1984.[2]

In December 1984, Goniwe called for boycott known as the "Black Christmas" of white-owned shops, infuriating the white business community. The boycott was successful as the Lingelihle community did not buy food or liquor from white-owned stores. On February 1985, at a funeral for Thozi Skweyiya, who was shot during the riots of 3 February, Goniwe and others appealed to the community to stop the violence.[6]

CRADORA meanwhile had held several meetings with the DET and its regional director, Giinther Merbold , in an attempt to get Goniwe reinstated. A senior DET official, De Beer, declared the case “closed”. After a community delegation to Cape Town, the DET decided to re-open the case and agreed to meet Goniwe in Cradock. Goniwe told them he wanted the school boycott to come to an end. CRADORA asked De Beer to help them get permission for a public meeting (there was a banning order for all meetings) on 29 March 1985, which De Beer did, and the meeting was held on Easter Monday. Goniwe said the children had to go back to school – after 15 months.[6]

In May, when it appeared Goniwe would be reinstated, the army and SAP raided Lingelihle, which was sealed off. Pamphlets linking CRADORA to “violence, communism and terrorism” were dropped from helicopters. Goniwe was verbally attacked over loudspeakers from the helicopters: “Goniwe did not give you water. The ANC is among you. Stay in your houses.” Ten hours later the operation ended with a blaring voice: “Thank you for your cooperation.”[6]

Goniwe's political influence in the township led to the formation of street committees where 17 000 residents were divided into seven zones. About 40 activists were assigned to these different areas and held meetings in each zone to elect officials and each household could vote for their street representatives. This came to be known as the “G-Plan” or “Goniwe’s Plan”. By late 1984, Cradock and the township of Lingelihle were seen as models of organisation by the United Democratic Front. The committee structures that Goniwe helped to set up were copied by other townships.[2]

In June 1985, the Cradock Security Police chief Major Eric Winter intensified surveillance over Goniwe, his cousin Mbulelo, Calata and Jacobs. The Deputy Minister of Defence Adriaan Vlok also visited Lingelihle township and the homes of the four activists.[3] In describing the situation at the time, Mbulelo said, "We were the four targeted people of Cradock, so in a sense one can say that is the legit Cradock Four as targeted by the state at the time."[7]

Assassination

On 27 June 1985, Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli (known as the Cradock Four) left for Port Elizabeth at about 10am. Goniwe as the UDF rural organiser in the Karoo was going to Port Elizabeth to address the movement's leadership. The vehicle that the four activists were travelling in was spotted by the police at Cookhouse, around lunchtime.[2]

In the afternoon, Goniwe attended meetings with his comrades. Goniwe's last meeting was at the house of UDF activist Michael Coetsee, finished at around 21h00. The four left at about 21h10, after Goniwe refused the invitation from fellow UDF member Derrick Swarts to stay over and not travel at night, saying he wanted to spend time with his family. The four were intercepted by a police roadblock outside Port Elizabeth. They were abducted, assaulted and burnt.[2]

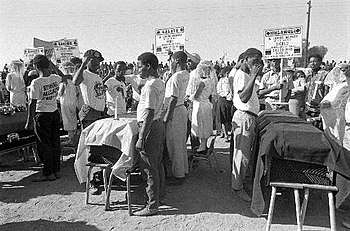

Mkhonto and Mhlauli's bodies were found in different parts of a dump near Bluewater Bay, Port Elizabeth. Goniwe and Calata's bodies were found in Bluewater Bay days later. Calata, Goniwe, Mhlauli and Mkhonto were buried in Cradock on 20 July 1985, at a massive political funeral attended by thousands of people from all over the country. Speakers at the funeral included Beyers Naudé, Allan Boesak and Steve Tshwete gave keynote addresses. A message from the then president of the ANC Oliver Tambo was read.[8] [9][3]

Inquest

The South African government denied its involvement in the murder of the Cradock Four. However, by early June 1985, a copy of the signal message form issuing their death warrant was anonymously sent to Transkei's Minister of Defence, Major-General Bantu Holomisa, who forwarded the document to Transkei's Director of Military Intelligence. The document proposed the permanent removal of Matthew Goniwe, Mbulelo Goniwe and Fort Calata from the community.[1]

A two-year inquest into the death of the Cradock Four began in 1987 (Inquest No. 626/87) under the Inquests Act No. 58 of 1959, headed by Magistrate E de Beer. At the end of the inquest on 22 February 1989, the magistrate found that the four had been killed by “unknown persons”. In 1992, President FW de Klerk called for a second inquest after the disclosure on 22 May 1992 by the New Nation newspaper of a top secret military signal calling for the "permanent removal from society" of Goniwe, Calata and Goniwe’s cousin, Mbulelo. The second inquest began on 29 March 1993 and ran for 18 months in terms of the Inquests Amendment. Judge Neville Zietsman, in delivering his verdict, found that the security forces were responsible for their deaths, although no individual was named as responsible.[3]

Legacy

In December 1999, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission refused amnesty to six of the former Port Elizabeth security policemen who were involved in the murder of the Cradock Four. The six security policemen are the late former security branch head Harold Snyman, Eric Alexander Taylor, Gerhardus Johannes Lotz, Nicolaas Janse van Rensburg, Johan van Zyl and Hermanus Barend du Plessis. Colonel Snyman gave the order for the killing of Goniwe, Sparrow Mkhonto, Fort Calata and Sicelo Mhlauli in 1985. Former Vlakplaas commander Eugene de Kock was the only one who was granted amnesty.[10]

In 2007, the then Deputy Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Rejoice Mabudafhasi launched the Cradock Four Garden of Remembrance and Vusubuntu Cultural village in honour of the Cradock Four on the N10 between Bedford and Cradock.[11]

In 2010, filmmaker, David Forbes, released his documentary about Matthew Goniwe. The production of the movie took years to produce because access to transcripts of amnesty hearings were so difficult to get hold of. Forbes had to use the Promotion of Access to Information Act No 2 of 2000 to finally get his hands on the information.[12]

See also

References

- "Unveiling the mystery of the Cradock Four: 25 years later". South African History Archives. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "Matthew Goniwe". South African History Online. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "Fort Calata". South African History Online. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "Sicelo Mhlauli". South African History Online. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "Sparrow Mkhonto". South African History Online. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "The Biography of Matthew Goniwe". The Cradock Four. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Mbabela, Zandile (23 April 2016). "Story behind Cradock Four picture". HeraldLIVE. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- "Ten years on, who killed Matthew Goniwe". Mail & Guardian. Mail & Guardian Online. 2 June 1995. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Biographies of the Calata family". Rhodes University. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "No amnesty for killers of Cradock Four". Independent News Online. 14 December 1999. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Magadla, Qaqamba (5 April 2016). "Neglected memorial to Cradock Four to receive(sic) a massive facelift". DispatchLIVE. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- "Cradock Four Memorial". SA Venues. Retrieved 5 October 2017.