The Blithedale Romance

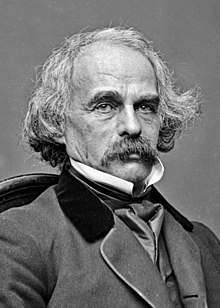

The Blithedale Romance (1852) is Nathaniel Hawthorne's third major romance. Its setting is a utopian farming commune based on Brook Farm, of which Hawthorne was a founding member and where he lived in 1841. The novel dramatizes the conflict between the commune's ideals and the members' private desires and romantic rivalries. In Hawthorne (1879), Henry James called it "the lightest, the brightest, the liveliest" of Hawthorne's "unhumorous fictions," while literary critic Richard Brodhead has described it as "the darkest of Hawthorne's novels."[1]

First edition title page. | |

| Author | Nathaniel Hawthorne |

|---|---|

| Genre | Romantic, Historical |

| Publisher | Ticknor and Fields |

Publication date | 1852 |

| Pages | 287 |

Plot summary

The story takes place primarily in the utopian community of Blithedale, presumably in the mid-1800s. The main character, Miles Coverdale, embarks on a quest for the betterment of the world through the agrarian lifestyle and community of the Blithedale Farm. The story begins with a conversation between Coverdale and Old Moodie, a character who reappears throughout the story. The legend of the mysterious Veiled Lady is introduced; she is a popular clairvoyant who disappears unannounced from the social scene. Coverdale then makes the voyage to Blithedale, where he is introduced to such characters as Zenobia and Mr. and Mrs. Silas Foster. At their first community dinner, they are interrupted by the arrival of Hollingsworth, a previous acquaintance of Coverdale, who is carrying a frail, pale girl. Though Hollingsworth believes the girl (whose age never is clarified) is an expected guest, none of the Blithedale citizens recognize her. She immediately develops a strong attachment to Zenobia, and reveals her name to be Priscilla.

Soon after, Coverdale becomes severely ill and is bedridden. During his sickness, he believes he is on the brink of death and develops a closeness with Hollingsworth due to their anxiety-ridden situation and discussion of worldly ideals. Hollingsworth and Zenobia take care of him, and he returns to health shortly. As he recovers and spring comes, the residents of the community begin to work the land successfully and prove to their neighbors the plausibility of their cause. Priscilla starts to open up, and relationships between the other characters develop as well. Tension in the friendship between Coverdale and Hollingsworth intensifies as their philosophical disagreements continue. Meanwhile, Zenobia and Hollingsworth become close, and rumor flies they might build a house together. Mr. Moodie makes a reappearance and asks about Priscilla and Zenobia for reasons to be revealed later. Coverdale then meets a stranger who turns out to be a Professor Westervelt. Westervelt also asks about Zenobia and Hollingsworth. Coverdale does not like the Professor, and when he is retreating in a tree he overhears the Professor talking to Zenobia and implying that they have a prior relationship.

At this point, the narrator of the story briefly switches to Zenobia as she tells a tale titled “The Silvery Veil.” She describes the Veiled Lady and her background, though it is never revealed whether her version of the story is true or not. After switching narration back to Coverdale, the story proceeds to Eliot's Pulpit, a place of rest and discourse for the four main characters (Coverdale, Hollingsworth, Priscilla, and Zenobia). There they discuss women's rights, and Zenobia and Hollingsworth agree, against Coverdale, on a more misogynistic point of view. Their disagreements intensify the next day when Hollingsworth and Coverdale discuss their hopes for the future of Blithedale. They disagree so thoroughly that Coverdale renounces Hollingsworth and effectively ends their friendship. A turning point in the novel, the drama culminates with Coverdale's leaving the farm and returning to the city. He there shows a sort of voyeurism, peeping through hotel windows at a young man and another family. While peeping, he spies Zenobia and Westervelt in another window. They notice, and embarrassed and curious, Coverdale visits them and gets chastised by Zenobia. She reveals that Priscilla is staying with them, and then all three leave Coverdale for an unnamed appointment. Motivated once more by curiosity, he seeks Old Moodie, who when drunk tells him the story of Fauntleroy, Zenobia, and Priscilla. It turns out that Old Moodie is Fauntleroy and the father of Zenobia, and was once a wealthy man. He fell from grace, but remarried later and had another child, Priscilla, making the two women half sisters.

Coverdale is extremely shocked and proceeds to a show of the Veiled Lady, where he recognizes Westervelt as the magician controlling the clairvoyant and Hollingsworth in the audience. He asks the whereabouts of Priscilla, and it is shortly revealed, when Hollingsworth removes the veil, that Priscilla is the Veiled Lady. All of the main characters then return and meet at Eliot's Pulpit. Zenobia accosts Hollingsworth for his love for Priscilla, expresses her depression, and acknowledges her sisterhood with Priscilla. However, Priscilla chooses Hollingsworth over her, and the three go their separate ways. When Zenobia realizes that Coverdale witnessed this scene, she asks him to tell Hollingsworth that he has “murdered” her and tells him that when they next meet it will be behind the “black veil,” representing death. She leaves and does not return. Hollingsworth, Coverdale, and Silas Foster form a search party and find Zenobia's body in the river. She is buried at Blithedale and given a simple funeral, at which Westervelt makes a last cryptic appearance and declares her suicide foolish. Hollingsworth is severely affected by the death, and it seems as she promised that Zenobia is haunting him. Priscilla is less affected due to her attachment solely to Hollingsworth, and the rest of the characters part and proceed with their lives. The last chapter reflects on the wisdom and ideals of Coverdale, now cynical about his purpose in life. The last sentence reveals cause for his bleak, apathetic outlook—he was in love with Priscilla.

Major characters

Miles Coverdale: The story's protagonist and narrator, Coverdale is a simple observer of the activities of the Blithedale farm. However, his narrative occasionally exaggerates or becomes dreamlike and is not entirely trustworthy.[2] At points in the novel, Coverdale seems to practice mild voyeurism. He is a professed supporter of women's equality, as evidenced in an argument with Hollingsworth, although he also views Zenobia's feminism as a symptom of romantic disillusionment. He is typically mild-mannered, though often strange and illogical. He is consistently curious about his surroundings, leading to his voyeurism and mostly unsupported speculations on his fellow residents. Though he seems to fancy Zenobia and certainly regards her as beautiful, in the last line of the story he confesses that he is truly in love with Priscilla. However, critics often identify a strongly homoerotic relationship between Coverdale and Hollingsworth.[3]

Old Moodie: Though introduced as Old Moodie, he was formerly known as Fauntleroy, a wealthy but immoral man who loses his riches in a financial scandal. He is separated from his beautiful wife and daughter and disowned by the rest of his family. Years later, poorer and wiser, he remarries and has a second daughter. Coverdale uses him to discover the backgrounds of Zenobia and Priscilla, who are his two daughters.

The Veiled Lady: She is a mystical character, first introduced as a public curiosity, who suddenly disappears from the public's eye. Her story is developed in a type of ghost story narrated by Zenobia in a segment titled The Silvery Veil. She is said to have been held captive by the curse of the veil, a symbol which in Hawthorne's literature typically represents secret sin.[4] She is controlled by the magician Westervelt, and is eventually revealed to be Priscilla herself when Hollingsworth removes the veil.

Hollingsworth: A philanthropist overly concerned with his own ideals, he comes to the farm with Priscilla having been told she has a place there. He becomes good friends with Coverdale during the other's sickness, but his attempts to recruit the other to his cause eventually cause enough tension for a split in the friendship. He believes in the reform of all sinners and attempts to use Blithedale and its residents to achieve these ends, instead of those supported by the group. He is rumored to have a relationship with Zenobia partway through the novel, and they plan on building a cottage together. However, he falls for Priscilla, saving her from the fate of the Veiled Lady, and breaks up with Zenobia, which causes her to commit suicide.

Silas Foster: Coverdale describes him as “lank, stalwart, uncouth, and grizzly-bearded.” He is the only resident that seems to be truly experienced in the art of farming. He is level-headed and sensible, and is the first to suggest Priscilla stay upon her arrival. He is one of the three men to search for and find Zenobia's body and, while displaying proper sadness and emotion, also accepts her death with the most ease.

Mrs. Foster: She is first to welcome Coverdale to Blithedale, wife of Silas Foster. She manages the farm and plays only a small role in the novel.

Zenobia: Beautiful and wealthy, she wears a different tropical flower in her hair every day. She is admired by both Hollingsworth and Coverdale, though both eventually fall for her sister Priscilla instead. Priscilla herself is also quite taken with the older woman and follows her around the farm. Zenobia's main vice is pride, and she has an unusual and unexplained prior relationship with Professor Westervelt. She is the daughter of Old Moodie's first, prosperous marriage when he was still referred to as Faunteleroy. She often is thought to be analogous to the author Margaret Fuller, who although not a resident of Brook Farm was a frequent visitor there.[5]

Priscilla: A fragile, mysterious girl brought to the farm by Hollingsworth. She makes intricate purses that Coverdale considers a “symbol of her mystery.” She is known to frequently pause as if responding to a call, though no other characters hear it. She becomes progressively more open and less frail throughout the novel and develops a strong attachment to Hollingsworth on top of her sisterly affections for Zenobia. She is eventually revealed to be the second daughter of Old Moodie, as well as the alter ego of the Veiled Lady. Hollingsworth frees her from the curse of the veil, and at the book's close, she remains attached to him.

Professor Westervelt: Stumbles into the plot looking for Priscilla and Zenobia. Coverdale takes an immediate distaste to him and describes him with such language as one would describe the devil. In fact, much of the imagery Coverdale uses, such as the flames on Westervelt's pin and the serpent-headed staff he carries are direct references to Satan. He presumably has a former, possibly romantic, relationship with Zenobia. He is revealed to be the magician controlling Priscilla near the end of the book, and his last appearance is at Zenobia's funeral where he criticizes her foolish suicide.

Contemporary and modern criticism

Following its publication, The Blithedale Romance was received with little enthusiasm by contemporary critics. As one reviewer claims, the preface which is merely a disclaimer of sorts, "is by no means the least important part of it".[6] In fact, to many reviews this simple, non-fictional disclaimer seems to be the most important part of the book. Many reviews refer to the preface of the novel and express skepticism in regard to Hawthorne's plea contained therein for the reader not to take the characters and occurrences of the novel as representative of real-life people and events. They claim that there is simply too much correlation between fiction and nonfiction. One reviewer states "so vividly does [Hawthorne] present to us the scheme at Brook Farm, to which some of our acquaintance were parties, so sharply and accurately does he portray some incidents of life there, that we are irresistibly impelled to fix the real names of men and women to the characters of his book".[7] As such they read into what Hawthorne writes about characters that have associated real-life figures.

However, other reviews, while stating that there is correlation between the fiction of the novel and reality, these correlations should not lead to association of fiction and non-fiction. One review states "we can recognize in the personages of his Romance individual traits of several real characters who were [at Brook Farm], but no one has his or her whole counterpart in one who was actually a member of the community. There was no actual Zenobia, Hollingsworth, or Priscilla there, and no such catastrophe as described ever occurred there".[8]

A great deal of modern criticism centers around the relation between fiction and non-fiction as well. Critics believe that when viewed as representative of Hawthorne's own life and beliefs, "The Blithedale Romance" provides insight into the mind of the author. According to critics, the novel can be seen as a reflection of the religious conflict Hawthorne faced throughout his life. Irving Howe summarizes this religious conflict, stating, "Throughout his life Hawthorne was caught up in what we would call a crisis of religious belief. His acute moral sense had been largely detached from the traditional context of orthodox faith, but it had found little else in which to thrive".[9] Although Hawthorne did not agree with Puritan dogmas, Transcendentalists often associated morality with observance of these dogmas. The novel presents an ironic contradiction between the perception of morality and actual morality, such as the "Utopian" Blithedale filled with sin and far less than "moral" individuals. Critics claim, therefore that Blithedale is an attempt by Hawthorne to represent morality as independent from faith.[10]

In a broader sense, critics have long argued that the majority of the people, places, and events of The Blithedale Romance can be traced back to Hawthorne's observations and experiences over his lifetime.[11] The most obvious of these correlations between fiction and reality is the similarity between Blithedale and Brook Farms, an actual experimental community in the 19th century of which Hawthorne was a part. In addition, the character of Coverdale is often associated with Hawthorne himself. However, according to critics this self-portrait is "a highly and mocking self-portrait, as if Hawthorne were trying to isolate and thereby exorcise everything within him that impedes full participation in life".[12] Critics have also argued for less obvious connections such as the connection between Zenobia and Margaret Fuller, a contemporary of Hawthorne.[13]

Context

The Blithedale Romance is a work of fiction based on Hawthorne's recollections of Brook Farm,[14] a short-lived agricultural and educational commune where Hawthorne lived from April to November 1841. The commune, an attempt at an intellectual utopian society, interested many famous Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller, though few of the Transcendentalists actually lived there.[15] In the novel's preface, Hawthorne describes his memories of this temporary home as "essentially a daydream, and yet a fact" which he employs as "an available foothold between fiction and reality." His feelings of affectionate scepticism toward the commune are reflected not only in the novel, but also in his journal entries and in the numerous letters he wrote from Brook Farm to Sophia Peabody, his future wife.

Hawthorne's claim that the novel's characters are "entirely fictitious" has been widely questioned. The character of Zenobia, for example, is said to have been modelled upon Margaret Fuller,[16] an acquaintance of Hawthorne and a frequent guest at Brook Farm. The circumstances of Zenobia's death, however, were not inspired by the shipwreck that ended Fuller's life but by the suicide of a certain Miss Martha Hunt, a refined but melancholy young woman who drowned herself in a river on the morning of July 9, 1845. Hawthorne helped to search for the body that night, and later recorded the incident at considerable length in his journal.[17] Suggested prototypes for Hollingsworth include Amos Bronson Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Horace Mann,[18] while the narrator is often supposed to be Hawthorne himself.[19]

Symbols

Flower: Zenobia wears a new exotic flower every day. It represents vitality, and all the other characters are focused on destroying it. Coverdale is always probing and investigating into her life. Hollingsworth uses her in his conspiracy to create an ideal society. Priscilla betrays her when she chooses Hollingsworth over her. Lastly Westervelt blackmails her. She ultimately destroys herself through suicide. The exotic flower is a symbol of her pride, life and vitality all of which the characters in the Blithedale Romance are set on destroying. Zenobia's main vice is pride; however it is why she is admired by all. Its physical representation is demonstrated through her exotic flower.[20]

Veil: The veil represents withdrawal and concealment. Priscilla, as the Veiled Lady, is private and hidden. The image of the veil appears with almost every character. Old Moodie with his alias and eye patch illustrates his use of concealment. Westervelt's gold teeth, Hollingsworth's philanthropic project are also examples of a withdrawal. Additionally, the whole community is withdrawn from society, as it is a secluded Utopian community. The veil is a constantly recurring theme throughout the novel. Concealment and withdrawal continually surface through all the characters.[21]

Spring/Fall: The novel starts in spring and ends in fall. Upon moving to Blithedale, Coverdale proclaims his own rebirth. Spring is full of warmth and hope, while fall is full of dark imagery. In spring, Coverdale recovers from his illness. In fall, it concludes with the mutilated, marbled, rigid corpse of Zenobia.[22]

Sickness: In the beginning of the novel, Coverdale becomes deathly ill and is bedridden. Hollingsworth cares for him and he returns to health. Priscilla is also sick and gradually regains her health as time elapses and she adjusts to Blithedale. As Roy R. Male Jr. wrote, “This sickness is what the book is about.” Coverdale's mental state also changes throughout the novel. Upon his return he emphasizes that there is a, "Sickness of the spirits [which] kept alternating with my flights of causeless buoyancy"[23]

Dreams: The dream of building a Utopian Society is just one of the dreams in the novel. As Daniel Hoffman wrote, "Whether Miles Coverdale is reporting what he has actually seen and heard, or what he has dreamed. Parts of the book indeed seem to rely on, to create, a stream-of-consciousness narration" Coverdale's dreams reveal his discovery and continued repression of his sexual desire of Zenobia.[24] There are dreams created in his imagination and memory, as well as the dreams in his sleep. All of which include the veil and mask imagery that recur in the novel.[25]

Style

The novel is written from a first-person limited point of view and the narrator is Miles Coverdale. Coverdale's narrative style is erratic and dreamlike, bringing a strange form of syntax to the novel that is more Coverdale's than Hawthorne's.[26] In a final chapter added after the original manuscript was completed but before publishing, Coverdale breaks the fourth wall and reveals that the writing takes place significantly after leaving Blithedale. He reveals the fates of the other characters from a still limited viewpoint.

The title identifies the novel as a romance, probably of the dark romantic type as Hawthorne (along with Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville) was considered a dark romantic writer. It displays the characteristic symbolism of Satan, magic and the supernatural frequently used in dark romantic literature. Themes of sin, guilt, and the betterment of humanity also appear in the novel through symbols like the veil and Blithedale itself. These too are indicators of the book's Transcendentalist background and romantic nature.

References

- Brodhead, Richard. Hawthorne, Melville, and the Novel, p. 111.

- Winslow, Joan. “New Light on Hawthorne's Miles Coverdale” The Journal of Narrative Technique Fall 1977 https://www.jstor.org/stable/30225619

- Berlant, Lauren. “Fantasies of Utopia in The Blithedale Romance”. American Literary History Spring 1989 https://www.jstor.org/stable/489970

- Sloan, Elizabeth. The Treatment of the Supernatural in Poe and Hawthorne. Ithaca: Cornell, 1930.

- The Brook Farm Community www.age-of-the-sage.org/transcendentalism/brook_farm.html

- "Christian Examiner" September 1852

- "Christian Examiner" September 1852

- Brownson's Quarterly Review (October 1852)

- Howe, Irving. Hawthorne: Pastoral and Politics in Ed. Gross, Seymour. "The Blithedale Romance". New York: Norton & Company, 1978. p. 288. ISBN 0-393-04449-1

- Howe, Irving. Hawthorne: Pastoral and Politics in Ed. Gross, Seymour. "The Blithedale Romance". New York: Norton & Company, 1978. p. 289. ISBN 0-393-04449-1

- Male, Roy R. The Pastoral Wasteland in Ed. Gross, Seymour. The Blithedale Romance. New York: Norton & Company, 1978. p. 297. ISBN 0-393-04449-1

- Howe, Irving. "Hawthorne: Pastoral and Politics" in Ed. Gross, Seymour. The Blithedale Romance. New York: Norton & Company, 1978. p. 290. ISBN 0-393-04449-1

- Male, Roy R. "The Pastoral Wasteland" in Ed. Gross, Seymour. The Blithedale Romance. New York: Norton & Company, 1978. p. 298. ISBN 0-393-04449-1

- McFarland, Philip. Hawthorne in Concord. New York: Grove Press, 2004. p. 149. ISBN 0-8021-1776-7

- While neither of them agreed to participate in the social experiment by living at the farm, they often visited the community. The Brook Farm Community www.age-of-the-sage.org/transcendentalism/brook_farm.html

- Blanchard, Paula. Margaret Fuller: From Transcendentalism to Revolution. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1987: 187. ISBN 0-201-10458-X

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Blithedale Romance: an Authoritative Text; Background and Sources; Criticism (Seymour Gross, Editor). New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978, pp. 253–257.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Blithedale Romance: an Authoritative Text; Background and Sources; Criticism (Seymour Gross, Editor). New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978, p. 270.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Blithedale Romance: an Authoritative Text; Background and Sources; Criticism (Seymour Gross, Editor). New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978, p. 272.

- Male, Roy R. Jr. "Toward the Waste Land: The theme of the Blithedale Romance" College English February 1955 https://www.jstor.org/stable/372340

- Male, Roy R. Jr. "Toward the Waste Land: The theme of the Blithedale Romance" College English February 1955 https://www.jstor.org/stable/372340

- Male, Roy R. Jr. "Toward the Waste Land: The theme of the Blithedale Romance" College English February 1955 https://www.jstor.org/stable/372340

- Male, Roy R. Jr. "Toward the Waste Land: The theme of the Blithedale Romance" College English February 1955 https://www.jstor.org/stable/372340

- Ross, Donald. "Dreams and Sexual Repression in the Blithedale Romance" PMLA October 1971 https://www.jstor.org/stable/461086

- Griffith, Kelley. "Form in The Blithedale Romance" American Literature March 1968 https://www.jstor.org/stable/2923695

- Griffith, Kelley. "Form in The Blithedale Romance" American Literature March 1968 https://www.jstor.org/stable/2923695

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Blithedale Romance at Project Gutenberg

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.