Texas Courts of Appeals

The Texas Courts of Appeals are part of the Texas judicial system. In Texas, all cases appealed from district and county courts, criminal and civil, go to one of the fourteen intermediate courts of appeals, with one exception: death penalty cases. The latter are taken directly to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the court of last resort for criminal matters in the State of Texas. The highest court for civil and juvenile matters is the Texas Supreme Court. While the Supreme Court (SCOTX) and the Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) each have nine members, the size of the intermediate court of appeals is set by statute and varies greatly.

The total number of appellate court seats currently stands at 80, ranging from three to thirteen per court. To equalize caseloads, the Texas Supreme Court regularly transfers batches of cases from one court to another. The transferee court must then apply the precedents of the court from which the case was sent, rather than its own, unless there is no controlling precedent from the court from which the appeal originated.

Appellate courts consisting of more than three justices hear and decide cases in panels of three. Occasionally, the entire court sits en banc to reconsider a prior panel decision and to assure consistency in the court's jurisprudence. The en banc process is also used to overrule prior precedent of the same court which its panels would otherwise have to follow. The precedents established by a court of appeals are binding on the lower courts in its own district, but not in others.

The First and Fourteenth Court of Appeals, both sitting in Houston in the historic Harris County Courthouse, have coinciding appellate districts, and occasionally hand down conflicting rulings on the same legal issue. Such conflicts may ultimately be resolved by the Texas Supreme Court (in civil cases) or Court of Criminal Appeals (in criminal cases). Decisions of the two courts of last resort on questions of law are binding on all state courts, and are also followed by federal courts when they hear cases governed by Texas state law.

The federal courts sitting in Texas apply state law when the case is not controlled by federal law or by the law of another jurisdiction based contractual choice of law or other basis for application of another's jurisdiction's law. Not infrequently the federal district courts sitting in Texas and the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals make guesses as to how the Texas Supreme Court would rule on an issue of state law that is still unsettled due to a conflict among the intermediate courts of appeals.[1] Such an issue may also be referred to the Texas Supreme Court by certified question,[2] but this procedure is rarely employed.

Like the members of the Texas Supreme Court and the Court of Criminal Appeals, the Justices of the intermediate Texas Courts of Appeals are elected in partisan elections to six-year terms. Many, however, are initially appointed by the Texas Governor to fill vacancies and then run as incumbents in the next election.

In the November 2018 general election, many Republican incumbents lost to Democrats, which entailed a switch from Republican control to majority control by Democrats in the Houston, Dallas, and Austin Courts of Appeals. Because not all members were up for reelection in 2018, however, these previously all-Republican courts now have a mixed partisan makeup. Unlike the now more diverse intermediate courts of appeals, the Texas Supreme Court remains under solid Republican control with no minority party representation at all, and is also less diverse demographically than the appellate judiciary as a whole. The intermediate Courts of Appeals have better representation of women and minorities. Some have female majorities and several are led by women as chief justices. Following the recent appointment of Jane Bland, who formerly served on the First Court of Appeals, the Texas Supreme Court now has three women jurists out of nine.

History

Courts of civil appeals in Texas were established in 1891 by constitutional amendment to help handle the increasing load of the court system. They had jurisdiction to hear appeals and mandamus petitions of any civil case from their region, with the regions decided by the legislature. The amendment provided that three-judge courts of appeals were to be created by legislature, and in 1892, the legislature created 3 courts of appeals: The First Court of Civil Appeals in Galveston, the Second Court of Civil Appeals in Fort Worth, and the Third Court of Civil Appeals in Austin. In 1893, the legislature created the Fourth Court of Civil Appeals in San Antonio out of territory taken from the first and third courts, and the Fifth Court of Appeals in Dallas. In 1907, the legislature created the Sixth Court of Civil Appeals in Texarkana. Then in 1911, the Seventh Court of Civil Appeals in Amarillo and the Eighth Court of Civil Appeals in El Paso were created. Soon after that, the Ninth Court of Civil Appeals was created in Beaumont in 1915, the Tenth was created in Waco in 1923, and the Eleventh was created in Eastland in 1925.[3]

In 1957, after Hurricane Audrey severely damaged the Galveston County Courthouse, the legislature moved the First Court of Appeals to Houston (where it sits today) and required Harris County to provide facilities.[4]

It was not until the 1970s that any more courts were created with the Twelfth Court of Civil Appeals in Tyler, the Thirteenth in Corpus Christi and Edinburg, and the Fourteenth in Houston. The latter exercises concurrent jurisdiction with the First Court.[3]

In 1977, the legislature increased the number of judges of various courts and authorized courts of appeals to sit in "panels" of not fewer than three judges.[4]

On September 1, 1981, all Courts of Civil Appeals were given criminal jurisdiction, and in 1985 a constitutional amendment was passed so that all courts were known as "Courts of Appeals" instead of "Courts of Civil Appeals."[4] Until 1981, all criminal appeals cases went directly to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and all cases involving capital punishment still do.[5][6]

In January 2019, a large number of newly elected justices took office, which required panels that included incumbents who were defeated in the November 2018 elections to be reconstituted. Because of similar turnover in many metropolitan trial courts, pending mandamus cases had to be abated and remanded for the new trial court judge to reconsider the challenged order of his or her predecessor.

The overall effect of the November 2018 Democratic sweep of the appellate courts in Houston, Dallas, and Austin was to make the intermediate appellate judiciary more diverse in terms of party affiliation, gender, and race/ethnicity, as can be seen by comparing the demographic statistics reported by the Office of Court Administration for 2018[7] and 2019.[8]

Jurisdictions

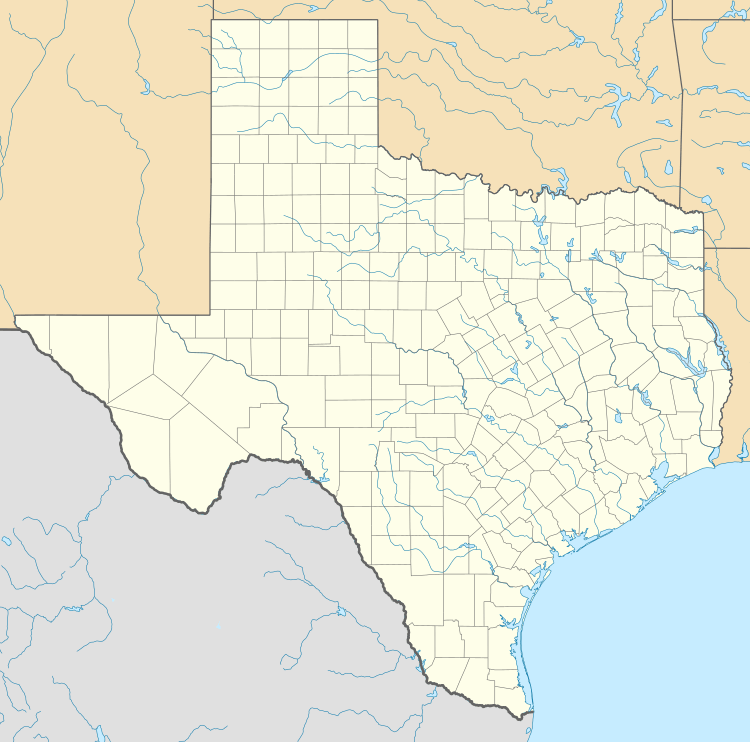

There are fourteen appellate districts each of which encompasses multiple counties and is presided over by a Texas Court of Appeals denominated by number:[9]

- First Court of Appeals of Texas – Houston (formerly Galveston), covering Austin, Brazoria, Chambers, Colorado, Fort Bend, Galveston, Grimes, Harris, Waller, and Washington counties

- Second Court of Appeals of Texas – Fort Worth, covering Archer, Clay, Cooke, Denton, Hood, Jack, Montague, Parker, Tarrant, Wichita, Wise, and Young counties

- Third Court of Appeals of Texas – Austin, covering Bastrop, Bell, Blanco, Burnet, Caldwell, Coke, Comal, Concho, Fayette, Hays, Irion, Lampasas, Lee, Llano, McCulloch, Milam, Mills, Runnels, San Saba, Schleicher, Sterling, Tom Green, Travis, and Williamson counties

- Fourth Court of Appeals of Texas – San Antonio, covering Atascosa, Bandera, Bexar, Brooks, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards, Frio, Gillespie, Guadalupe, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kendall, Kerr, Kimble, Kinney, La Salle, Mason, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Menard, Real, Starr, Sutton, Uvalde, Val Verde, Webb, Wilson, Zapata, and Zavala counties

- Fifth Court of Appeals of Texas – Dallas, covering Collin, Dallas, Grayson, Hunt, Kaufman, and Rockwall counties

- Sixth Court of Appeals of Texas – Texarkana, covering Bowie, Camp, Cass, Delta, Fannin, Franklin, Gregg, Harrison, Hopkins, Hunt, Lamar, Marion, Morris, Panola, Red River, Rusk, Titus, Upshur, and Wood counties

- Seventh Court of Appeals of Texas – Amarillo, covering Armstrong, Bailey, Briscoe, Carson, Castro, Childress, Cochran, Collingsworth, Cottle, Crosby, Dallam, Deaf Smith, Dickens, Donley, Floyd, Foard, Garza, Gray, Hale, Hall, Hansford, Hardeman, Hartley, Hemphill, Hockley, Hutchinson, Kent, King, Lamb, Lipscomb, Lubbock, Lynn, Moore, Motley, Ochiltree, Oldham, Parmer, Potter, Randall, Roberts, Sherman, Swisher, Terry, Wheeler, Wilbarger, and Yoakum counties.

- Eighth Court of Appeals of Texas – El Paso, covering Andrews, Brewster, Crane, Crockett, Culberson, El Paso, Hudspeth, Jeff Davis, Loving, Pecos, Presidio, Reagan, Reeves, Terrell, Upton, Ward, and Winkler counties

- Ninth Court of Appeals of Texas – Beaumont, covering Hardin, Jasper, Jefferson, Liberty, Montgomery, Newton, Orange, Polk, San Jacinto, and Tyler counties

- Tenth Court of Appeals of Texas – Waco, covering Bosque, Brazos, Burleson, Coryell, Ellis, Falls, Freestone, Hamilton, Hill, Johnson, Leon, Limestone, Madison, McLennan, Navarro, Robertson, Somervell, and Walker counties

- Eleventh Court of Appeals of Texas – Eastland, covering Baylor, Borden, Brown, Callahan, Coleman, Comanche, Dawson, Eastland, Ector, Erath, Fisher, Gaines, Glasscock, Haskell, Howard, Jones, Knox, Martin, Midland, Mitchell, Nolan, Palo Pinto, Scurry, Shackelford, Stephens, Stonewall, Taylor, and Throckmorton counties

- Twelfth Court of Appeals of Texas – Tyler, covering Anderson, Angelina, Cherokee, Gregg, Henderson, Houston, Nacogdoches, Rains, Rusk, Sabine, San Augustine, Shelby, Smith, Trinity, Upshur, Van Zandt, and Wood counties

- Thirteenth Court of Appeals of Texas – Corpus Christi and Edinburg, covering Aransas, Bee, Calhoun, Cameron, De Witt, Goliad, Gonzales, Hidalgo, Jackson, Kenedy, Kleberg, Lavaca, Live Oak, Matagorda, Nueces, Refugio, San Patricio, Victoria, Wharton, and Willacy counties

- Fourteenth Court of Appeals of Texas – Houston, covering Austin, Brazoria, Chambers, Colorado, Fort Bend, Galveston, Grimes, Harris, Waller, and Washington counties

The counties of Gregg, Rusk, Upshur, and Wood are in the jurisdictions of both the Sixth and Twelfth Courts, while Hunt County is in the jurisdiction of both the Fifth and Sixth Courts. The Thirteenth Court of Appeals has seats in two cities: Corpus Christi and Edinburg.

Opinion output and public access to opinions and orders

Collectively the Texas Courts of Appeals issue close to 10,000 opinions a year (9,909 in FY 2018) which are almost equally divided between civil and criminal cases.[10] The number is high because appeals to these courts are "of right" and each case must be decided with an opinion, even if the disposition is in the form of a voluntary dismissal or an involuntary dismissal for noncompliance with briefing rules or a fatal jurisdictional defect.

Although the COA follow different conventions in the formatting of their opinions, all are issued in standard PDF and are posted on the COA's respective websites, where they can be looked up through the online docket sheet created for each case. The courts' Case Search portal allows searches by appellate case number, but also by party name and attorney name or bar number, and by other case attributes. Most COAs also make other documents filed in a case available online, including briefs, letters, and notices. The issued opinions can also be found on Google Scholar (CaseLaw) and on other repositories of appellate opinions. Google Scholar additionally includes procedural orders in its database, which are linked to the pages featuring the opinions by the hot-linked appellate case number. Whereas the courts issue majority and dissenting/concurring opinions as separate PDF documents, Google Scholar combines them into one page and displays onscreen in a larger font and more user-friendly format, in addition to providing much better search functionality and hotlinks to cited cases if they are available from its database.

Dissents and Concurrences

Only about 1% of the issued COA opinions are dissents. Concurrences (separate opinions in which a justice agrees with the disposition, but not with the reasons for it, or only in part) accounted for 7% in 2018, up from 0.5% the previous year.[11] The proportion of dissents and concurrences will likely be higher in 2019 and beyond because the largest courts, which were previously controlled by Republicans, now have mixed partisan membership due to the Democratic sweep in 2018 that replaced Republican incumbents who were up for re-election that year.

Party affiliation and mixed composition are not the only sources of disagreement that manifest themselves in dissents. Kem Thompson Frost, the Chief Justice of the Fourteenth Court of Appeals, is known as an independent thinker and prolific dissenter. She wrote a total of 21 concurring or dissenting opinions in FY 2018 while her counterpart in the First Court of Appeals, Chief Justice Sherry Radack, wrote none.[12] Both presided over all-Republican courts, although one member on the First Court who had been elected as a Republican, Justice Terry Jennings,[13] switched to the Democrats and also wrote large number of separate opinions (19).

Statewide, there were 175 dissents and concurrences in Fiscal Year 2018, out of a total of 6,540 merits opinions. The total tally was 9,909, which includes per curiam opinions. As seen by the data for the Houston Courts of Appeals, individual justices can have a big impact on their respective court's comparative ranking, and on the statewide total.

By definition, a dissent in the Court of Appeals does not decide the case. Dissents (and concurrences) are nevertheless important because they typically highlight unsettled areas of the law or splits among the Courts of Appeals, and increase the chance that Texas Supreme Court will exercise discretionary review if a petition is filed in a case that drew a dissent in the Court of Appeals.

References

- Boren v. U.S. Nat'l Bank Ass'n, 807 F.3d 99, 105-6 (5th Cir. 2015)(Where, as here, the proper resolution of the case turns on the interpretation of Texas law, we are bound to apply Texas law as interpreted by the state's highest court." Am. Int'l Specialty Lines Ins. Co. v. Rentech Steel LLC, 620 F.3d 558, 564 (5th Cir.2010) (internal quotations and alterations omitted). Because the Texas Supreme Court has not decided whether a lender may abandon its acceleration of a loan by its own unilateral actions and, if so, what actions it must take to effect abandonment, we must make an "Erie guess" as to how the Court would resolve this issue. Id.)

- TEX. CONST. Art. V, § 3-c(a) ("The supreme court [has] jurisdiction to answer questions of state law certified from a federal appellate court."); TEX. R. APP. P. 58 (certified questions of law).

- About the Court

- Welcome to the official site of the First Court of Appeals of Texas!

- Justices of Texas 1836–1986 – Timeline of the Texas Supreme Court and Court of Criminal Appeals Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

- Office of Court Administration (Texas). "Profile of Appellate and Trial Judges as of Sep. 1, 2018" (PDF). Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- Office of Court Administration (Texas). "Profile of Appellate and Trial Judges as of Sep. 1, 2019" (PDF). Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- Tex. Govt. Code Ann. §22.201 (Vernon 2005)

- Office of Court Administration [Texas]. "Annual Statistical Report for the Texas Judiciary - Fiscal Year 2018" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-11-28.

- Office of Court Administration [Texas]. "Annual Report for the Texas Judiciary - Fiscal Year 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-11-28.

- Office of Court Administration. "Annual Statistical Supplement FY 2018 - Courts of Appeals Activity". Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- Christian, Carol; Chronicle, Chron com / Houston (2016-10-13). "Texas Republican judge who performed same-sex wedding, switched parties reports 'no backlash'". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2019-12-09.