Tetragonal disphenoid honeycomb

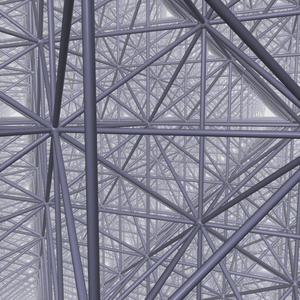

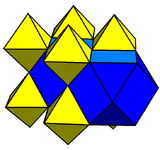

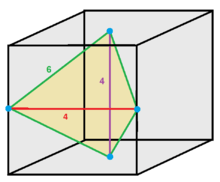

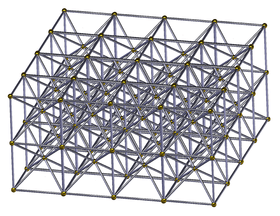

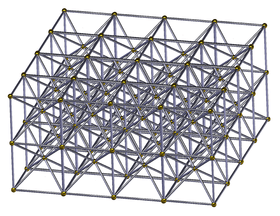

The tetragonal disphenoid tetrahedral honeycomb is a space-filling tessellation (or honeycomb) in Euclidean 3-space made up of identical tetragonal disphenoidal cells. Cells are face-transitive with 4 identical isosceles triangle faces. John Horton Conway calls it an oblate tetrahedrille or shortened to obtetrahedrille.[1]

| Tetragonal disphenoid tetrahedral honeycomb | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | convex uniform honeycomb dual |

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagram | |

| Cell type |  Tetragonal disphenoid |

| Face types | isosceles triangle {3} |

| Vertex figure |  tetrakis hexahedron |

| Space group | Im3m (229) |

| Symmetry | [[4,3,4]] |

| Coxeter group | , [4,3,4] |

| Dual | Bitruncated cubic honeycomb |

| Properties | cell-transitive, face-transitive, vertex-transitive |

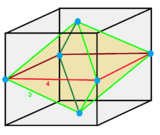

A cell can be seen as 1/12 of a translational cube, with its vertices centered on two faces and two edges. Four of its edges belong to 6 cells, and two edges belong to 4 cells.

The tetrahedral disphenoid honeycomb is the dual of the uniform bitruncated cubic honeycomb.

Its vertices form the A*

3 / D*

3 lattice, which is also known as the Body-Centered Cubic lattice.

Geometry

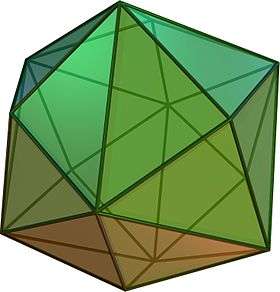

This honeycomb's vertex figure is a tetrakis cube: 24 disphenoids meet at each vertex. The union of these 24 disphenoids forms a rhombic dodecahedron. Each edge of the tessellation is surrounded by either four or six disphenoids, according to whether it forms the base or one of the sides of its adjacent isosceles triangle faces respectively. When an edge forms the base of its adjacent isosceles triangles, and is surrounded by four disphenoids, they form an irregular octahedron. When an edge forms one of the two equal sides of its adjacent isosceles triangle faces, the six disphenoids surrounding the edge form a special type of parallelepiped called a trigonal trapezohedron.

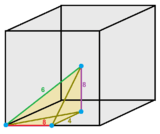

An orientation of the tetragonal disphenoid honeycomb can be obtained by starting with a cubic honeycomb, subdividing it at the planes , , and (i.e. subdividing each cube into path-tetrahedra), then squashing it along the main diagonal until the distance between the points (0, 0, 0) and (1, 1, 1) becomes the same as the distance between the points (0, 0, 0) and (0, 0, 1).

Hexakis cubic honeycomb

| Hexakis cubic honeycomb Pyramidille[2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Dual uniform honeycomb |

| Coxeter–Dynkin diagrams | |

| Cell | Isosceles square pyramid |

| Faces | Triangle square |

| Space group Fibrifold notation | Pm3m (221) 4−:2 |

| Coxeter group | , [4,3,4] |

| vertex figures | |

| Dual | Truncated cubic honeycomb |

| Properties | Cell-transitive |

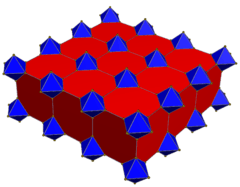

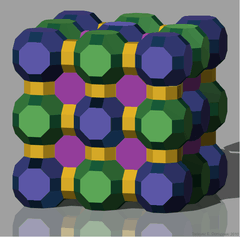

The hexakis cubic honeycomb is a uniform space-filling tessellation (or honeycomb) in Euclidean 3-space. John Horton Conway calls it a pyramidille.[3]

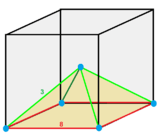

Cells can be seen in a translational cube, using 4 vertices on one face, and the cube center. Edges are colored by how many cells are around each of them.

It can be seen as a cubic honeycomb with each cube subdivided by a center point into 6 square pyramid cells.

There are two types of planes of faces: one as a square tiling, and flattened triangular tiling with half of the triangles removed as holes.

| Tiling plane |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | p4m, [4,4] (*442) | pmm, [∞,2,∞] (*2222) |

Related honeycombs

It is dual to the truncated cubic honeycomb with octahedral and truncated cubic cells:

If the square pyramids of the pyramidille are joined on their bases, another honeycomb is created with identical vertices and edges, called a square bipyramidal honeycomb, or the dual of the rectified cubic honeycomb.

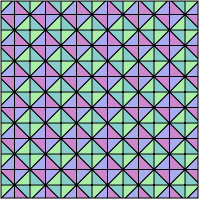

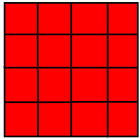

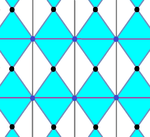

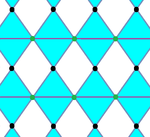

It is analogous to the 2-dimensional tetrakis square tiling:

Square bipyramidal honeycomb

| Square bipyramidal honeycomb Oblate octahedrille[4] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Dual uniform honeycomb |

| Coxeter–Dynkin diagrams | |

| Cell | Square bipyramid |

| Faces | Triangles |

| Space group Fibrifold notation | Pm3m (221) 4−:2 |

| Coxeter group | , [4,3,4] |

| vertex figures | |

| Dual | Rectified cubic honeycomb |

| Properties | Cell-transitive, Face-transitive |

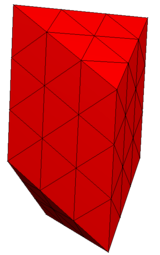

The square bipyramidal honeycomb is a uniform space-filling tessellation (or honeycomb) in Euclidean 3-space. John Horton Conway calls it an oblate octahedrille or shortened to oboctahedrille.[5]

A cell can be seen positioned within a translational cube, with 4 vertices mid-edge and 2 vertices in opposite faces. Edges are colored and labeled by the number of cells around the edge.

It can be seen as a cubic honeycomb with each cube subdivided by a center point into 6 square pyramid cells. The original cubic honeycomb walls are removed, joining pairs of square pyramids into square bipyramids (octahedra). Its vertex and edge framework is identical to the hexakis cubic honeycomb.

There is one type of plane with faces: a flattened triangular tiling with half of the triangles as holes. These cut face-diagonally through the original cubes. There are also square tiling plane that exist as nonface holes passing through the centers of the octahedral cells.

| Tiling plane |

Square tiling "holes" |

flattened triangular tiling |

|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | p4m, [4,4] (*442) | pmm, [∞,2,∞] (*2222) |

Related honeycombs

It is dual to the rectified cubic honeycomb with octahedral and cuboctahedral cells:

Phyllic disphenoidal honeycomb

| Phyllic disphenoidal honeycomb Eighth pyramidille[6] | |

|---|---|

| (No image) | |

| Type | Dual uniform honeycomb |

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagrams | |

| Cell | Phyllic disphenoid |

| Faces | Rhombus Triangle |

| Space group Fibrifold notation Coxeter notation | Im3m (229) 8o:2 [[4,3,4]] |

| Coxeter group | [4,3,4], |

| vertex figures | |

| Dual | Omnitruncated cubic honeycomb |

| Properties | Cell-transitive, face-transitive |

The phyllic disphenoidal honeycomb is a uniform space-filling tessellation (or honeycomb) in Euclidean 3-space. John Horton Conway calls this an Eighth pyramidille.[7]

A cell can be seen as 1/48 of a translational cube with vertices positioned: one corner, one edge center, one face center, and the cube center. The edge colors and labels specify how many cells exist around the edge.

Related honeycombs

It is dual to the omnitruncated cubic honeycomb:

See also

References

- Symmetry of Things, Table 21.1. Prime Architectonic and Catopric tilings of space, p.293, 295

- Symmetry of Things, Table 21.1. Prime Architectonic and Catopric tilings of space, p.293, 296

- Symmetry of Things, Table 21.1. Prime Architectonic and Catopric tilings of space, p.293, 296

- Symmetry of Things, Table 21.1. Prime Architectonic and Catopric tilings of space, p.293, 296

- Symmetry of Things, Table 21.1. Prime Architectonic and Catopric tilings of space, p.293, 295

- Symmetry of Things, Table 21.1. Prime Architectonic and Catopric tilings of space, p.293, 298

- Symmetry of Things, Table 21.1. Prime Architectonic and Catopric tilings of space, p.293, 298

- Gibb, William (1990), "Paper patterns: solid shapes from metric paper", Mathematics in School, 19 (3): 2–4, reprinted in Pritchard, Chris, ed. (2003), The Changing Shape of Geometry: Celebrating a Century of Geometry and Geometry Teaching, Cambridge University Press, pp. 363–366, ISBN 0-521-53162-4.

- Senechal, Marjorie (1981), "Which tetrahedra fill space?", Mathematics Magazine, Mathematical Association of America, 54 (5): 227–243, doi:10.2307/2689983, JSTOR 2689983.

- Conway, John H.; Burgiel, Heidi; Goodman-Strauss, Chaim (2008). "21. Naming Archimedean and Catalan Polyhedra and Tilings". The Symmetries of Things. A K Peters, Ltd. pp. 292–298. ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5.