Tepe Sialk

Tepe Sialk (Persian: تپه سیلک) is a large ancient archeological site (a tepe, "hill, tell") in a suburb of the city of Kashan, Isfahan Province, in central Iran, close to Fin Garden. The culture that inhabited this area has been linked to the Zayandeh River Culture.[1]

تپه سیلک | |

Tepe Sialk | |

Shown within Iran | |

| Location | Isfahan Province, Iran |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°58′08″N 51°24′17″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

History

A joint study between Iran's Cultural Heritage Organization, the Louvre, and the Institut Francais de Recherche en Iran also verifies the oldest settlements in Sialk to date to around 6000-5500 BC.[2][3] The Sialk ziggurat was built around 3000 BC.

Sialk, and the entire area around it, is thought to have originated as a result of the pristine large water sources nearby that still run today. The Cheshmeh ye Soleiman ("Solomon's Spring") has been bringing water to this area from nearby mountains for thousands of years. The Fin garden, built in its present form in the 17th century, is a popular tourist attraction. It is here that the kings of the Safavid dynasty would spend their vacations away from their capital cities. It is also here that Piruz Nahavandi (Abu-Lu'lu'ah), the Persian assassin of Caliph Umar, is buried. All these remains are located in the same location where Sialk is.

Archaeology

Tepe Sialk was excavated for three seasons (1933, 1934, and 1937) by a team headed by Roman Ghirshman and his wife Tania Ghirshman.[4][5][6] Studies related to the site were conducted by D.E. McCown, Y. Majidzadeh, and P. Amieh.[7][8] Excavation was resumed for several seasons between 1999 and 2004 by a team from the University of Pennsylvania and Iran's Cultural Heritage Organization led by Sadegh Malek Shahmirzadi called the Sialk Reconsideration Project.[9][10][11][12] Since 2008 an Iranian team led by Hassan Fazeli Nashli and supported by Robin Coningham of the University of Durham have worked at the northern mound finding 6 Late Neolithic burials.[13]

Artifacts from the original dig ended up mostly at the Louvre, while some can be found at the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the National Museum of Iran and in the hands of private collectors.

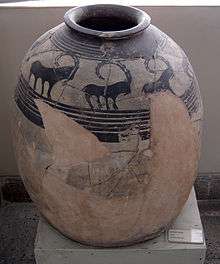

These artifacts consisted of some very fine painted potteries.[14]

Northern mound

The northern mound (tell) is the oldest; the occupation dates back to the end of the seventh millennium BC. The mound is composed of two levels: Sialk I (the oldest), and Sialk II. Sialk I-level architecture is relatively rudimentary. Tombs containing pottery have been uncovered. The ceramic is initially rather rough, then becomes of better quality with the time.[15]

Zagheh archaic painted ware (c. 6000–5500 BC) is found in Tepe Sialk I, sub-levels 1–2. This is the early painted ware, that was first excavated at Tepe Zagheh in the Qazvin plain.[16] In sub-periods 3, 4 and 5, the pottery has a clear surface with painted decoration. Stone or bone tools were still used.

The Sialk II level sees the first appearance of metallurgy. The archaeological material found in the buildings of this period testifies to increasing links with the outside world.

Southern mound

The southern mound (tell) includes the Sialk III and IV levels. The first, divided into seven sub-periods, corresponds to the fifth millennium and the beginning of the fourth (c. 4000 BC). This period is in continuity with the previous one, and sees the complexity of architecture (molded bricks, use of stone) and crafts, especially metallurgical.

Metallurgy

Evidence demonstrates that Tepe Sialk was an important metal production center in central Iran during the Sialk III and Sialk IV periods. A significant amount of metallurgical remains were found during the excavations in the 1990s and later. This includes large amounts of slag pieces, litharge cakes, and crucibles and moulds.[17]

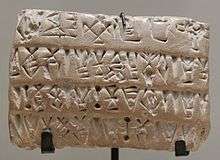

Sialk IV level begins in the second half of the fourth millennium, and ends with the abandonment of the site at the beginning of the third millennium. For the oldest sub-periods of the Sialk IV, there are links with the Mesopotamian civilizations of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr.

Later on, the material is similar to that of Susa III (Proto-Elamite level), so this is where the Proto-Elamite horizon at Sialk is located, as is also evidenced by the discovery here of some Proto-Elamite clay tablets.

The ruins of what would be the oldest Ziggurat in the world are found at this same Sialk IV level.

Second millennium BC

After an abandonment of more than a millennium, the Sialk site is reoccupied in the second half of the second millennium. This last phase of occupation of the site is divided into two periods: Sialk V and Sialk VI. The archaeological material of these two levels has been mostly found in the two necropolises, called necropolis A and necropolis B.

The first represents the Sialk V level. Here are found weapons and other objects in bronze, as well as jewelry, and some iron items. The ceramic is gray-black, or red, sometimes with some decorations that consist of geometric patterns, and can be compared to items coming from the sites in Gorgan valley (the later levels of Tureng Tepe, and Tepe Hissar).

Images

Details of the wall of the second platform of the first tepe.

Details of the wall of the second platform of the first tepe. Tomb.

Tomb. Renovated buildings.

Renovated buildings. Ghirshman's team in Sialk in 1934; seated from R to L: Roman Ghirshman, Tania Ghirshman, and Dr. Contenau.

Ghirshman's team in Sialk in 1934; seated from R to L: Roman Ghirshman, Tania Ghirshman, and Dr. Contenau. Pottery from Sialk.

Pottery from Sialk.

Relative chronology

See also

- Ancient Iranian history

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- Elamite Empire

- Iranian Architecture

- Kashan

- Gerdkooh ancient hill

- List of Iranian castles

Notes

- Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran (CHN) report: "Zayandeh Rood Civilization Linked to Marvdasht and Sialk". Accessed January 30, 2007. Link: Chnpress.com Archived 2009-02-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Fazeli, H., Beshkani A., Markosian A., Ilkani H., Young R. L. 2010 The Neolithic to Chalcolithic Transition in the Qazvin Plain, Iran: Chronology and Subsistence Strategies: in Archäologische Mitteilungen Aus Iran and Turan 41, pp. 1-17

- Matthews, R. and Nashli, H. F., eds. 2013 The Neolithisation of Iran: the formation of new societies. British Association for Near Eastern Archaeology and Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp272.

- Roman Ghirshman, Fouilles de Sialk près de Kashan, 1933, 1934, 1937, vol. 1, Paul Geuthner, 1938

- Ghirshman, Fouilles de Sialk, vol. 2, Paul Geuthner, 1939

- Spyoket, Agnès. "Ghirshman, Tania" (PDF). Breaking Ground: Women in Old World Archaeology. Translated by Sylvie Marshall. Brown University.

- D. E. McCown, The Comparative Stratigraphy of Early Iran, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization no. 23, Oriental Institute of Chicago, 1942

- Yousef Majidzadeh, Correction of the Internal Chronology for the Sialk III Period on the Basis of the Pottery Sequence at Tepe Ghabristan, Iran, vol. 16, pp. 93-101, 1978

- S.M. Shahmirzadi, The Ziggurat of Sialk, Sialk Reconsideration Project Report No. 1, Archaeological Research Center. Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, 2002, (Persian)

- S.M. Shahmirzadi, The Silversmiths of Sialk, Sialk Reconsideration Project Report No. 2, Archaeological Research Center. Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, 2003, (Persian)

- S.M. Shahmirzadi, The Potters of Sialk, Sialk Reconsideration Project Report No. 3, Archaeological Research Center. Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, 2004, (Persian)

- S.M. Shahmirzadi, The Smelters of Sialk, Sialk Reconsideration Project Report No. 4, Archaeological Research Center. Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, 2005, (Persian)

- A. Sołtysiak and H. Fazeli Nashli, Short Fieldwork Report: Tepe Sialk (Iran), seasons 2008–2009, Bioarchaeology of the Near East, vol. 4, pp.69–73, 2010

- Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 17. ISBN 0-395-13592-3.

- Les Recherches Archéologiques Françaises en Iran. Novembre 2001, Téhéran. Institut Français de Recherche en Iran, Musee du Louvre, ICHO

- Robert H. Dyson (2011), CERAMICS: The Neolithic Period through the Bronze Age in Northeastern and North-central Persia. iranicaonline.org

- Nezafati N, Pernicka E, Shahmirzadi SM. Evidence on the ancient mining and metallurgy at Tappeh Sialk (Central Iran) In: Yalcin U, Özbal H, Pasamehmetoglu HG, editors. Ancient Mining in Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean. Ankara: Atilim University; 2008. p. 329–349. researchgate.net

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.

References

- Les recherches archéologiques françaises en Iran. November 2001, Téhéran. Institut Français de Recherche en Iran, Musée du Louvre, ICHO.

- Yousef Majidzadeh, Sialk III and the Pottery Sequence at Tepe Ghabristan: The Coherence of the Cultures of the Central Iranian Plateau, Iran, vol. 19, 1981

- Ṣādiq Malik Šahmīrzādī, Sialk: The Oldest Fortified Village of Iran: Final Report, Iranian Center for Archaeological Research, 2006, ISBN 9789644210945

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tepe Sialk. |