Tennessee State Prison

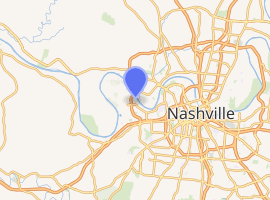

Tennessee State Prison is a former correctional facility located near downtown Nashville, Tennessee. It opened in 1898 and closed since 1992 because of overcrowding concerns.[1] The mothballed facility was severely damaged by an EF3 tornado in the tornado outbreak of March 2–3, 2020.[2]

Main entrance, 2006 | |

| |

| Location | Nashville, Tennessee |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36.1772°N 86.8654°W |

| Status | Closed 1992 |

| Security class | High/Medium security |

| Capacity | 1,400 |

| Opened | 1898 |

History

Tennessee State Prison, formerly the Tennessee State Penitentiary, is a former correctional facility located near downtown Nashville, Tennessee. Opened in 1898, the prison has been closed since 1992.[1]

The original Tennessee State Penitentiary became operational on January 1st, 1831 with 200 cells, a warden’s residence, and a hospital. Modeled after the Auburn Penitentiary in both discipline and design, the prison was the first of its kind in Tennessee and the South. Inmates were subject to practices championed by the Auburn model such as "during the day the prisoners, with downcast eyes, labored silently together in workshops, while at night they slept alone in separate cells. Under no circumstances could they communicate with one another, and only when necessity demanded could they receive letters or calls from relatives and friends."[3] The prison housed both men and women, with the first male inmate registered in 1831 and the first female inmate registered in 1840. A separate women’s wing was opened in 1892 but overcrowding soon forced the men and women to be housed together. The original Tennessee State Penitentiary on Church Street was demolished later in 1898, and salvageable materials were used in the construction of outbuildings at the new facility, creating a physical link from 1831 to the present. The proposed prison design called for the construction of a fortress-like structure patterned after the penitentiary at Auburn, New York, made famous for the lockstep marching, striped prisoner uniforms, nighttime solitary confinement, and daytime congregate work under strictly enforced silence. The new Tennessee prison contained 800 small cells, each designed to house a single inmate. In addition, an administration building and other smaller buildings for offices, warehouses, and factories were built within the twenty-foot (6.15m) high, three-foot (1 m) thick rock walls. The plan also provided for a working farm outside the walls and mandated a separate system for younger offenders to isolate them from older, hardened criminals. A separate women's wing was built on the northwest corner of the grounds that housed the female inmates who worked on the farm as well[4].

The prison was built by Enoch Guy Elliott who was married to Lady Ida Beasley Elliott (Missionary to Burma). Gov. Turney made Enoch Guy Elliott the Chief Warden of the old prison and then during the building of the second prison, Enoch used primarily prison labor to build the new prison.

Construction costs for this second Tennessee State Penitentiary exceeded US$500,000 (US$12.3 million in 2007 dollars), not including the price of the land. The prison's 800 cells opened to receive prisoners on February 12, 1898, and that day admitted 1,403 prisoners, creating immediate overcrowding. To a greater or lesser extent, overcrowding persisted throughout the next century.

In 1863, the Union Army took hold of the State Penitentiary and used it as a military prison. Under Union occupation, the prison population tripled and conditions worsened. Convicts were leased to the federal government by the Occupation Government of Tennessee to help repay their mounting debts. Among the prisoners held during this time was Mark Cockrill, a Confederate sympathizer whose West Nashville property would later be purchased for the construction of the new prison. Following the Civil war, the percentage of black inmates in the state of Tennessee increased dramatically, from roughly 5% of the prison’s population prior to the civil war, to about 62% in 1869. The proportion of black women in prison was significantly higher to black men in relation to whites, with all female prisoners in Tennessee in 1868 being African American women[5].

Every convict was expected to defray a portion of the cost of incarceration by performing physical labor. Inmates worked up to sixteen hours per day for meager rations and unheated, unventilated sleeping quarters. The 1840s saw a rise in the use of prison labor, with inmates being employed in the construction of the state capitol building in Nashville. Prison labor was so lucrative that the state prison became a revenue-generating system that came in direct competition with free laborers. The State also contracted with private companies to operate factories inside the prison walls using convict labor. In 1870 the state penitentiary reached a deal with the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company, establishing the first convict leasing program in the country. This only added to growing frustrations among free laborers who staged a strike against the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company in 1871. Though the effort was ultimately defeated, it was the first of many revolts against the convict leasing system.The State also contracted with private companies to operate factories inside the prison walls using convict labor[4].

The Tennessee State Penitentiary had its share of problems. In 1902, seventeen prisoners blew out the end of one wing of the prison, killing one inmate and allowing the escape of two others who were never recaptured. Later, a group of inmates seized control of the segregated white wing and held it for eighteen hours before surrendering. In 1907 several convicts commandeered a switch engine and drove it through a prison gate. In 1938 inmates staged a mass escape. Several serious fires ignited at the penitentiary, including one that destroyed the main dining room. Riots occurred in 1975 and 1985.

In 1989 the Tennessee Department of Correction opened a new penitentiary, the Riverbend Maximum Security Institution at Nashville. The old Tennessee State Penitentiary closed in June 1992. As part of the settlement in a class action suit, Grubbs v. Bradley (1983), the Federal Court issued a permanent injunction prohibiting the Tennessee Department of Correction from ever again housing inmates at the Tennessee State Prison.

The former prison was severely damaged by an EF3 tornado in the tornado outbreak of March 2–3, 2020.[2]

In films and television

It has been the location for the films Framed, Nashville, Marie, Ernest Goes to Jail, Against the Wall, Last Dance, The Green Mile, The Last Castle, and Walk the Line, as well as, two of Eric Church's music videos "Lightning" and "Homeboy," Cage The Elephant's music video for "Cold Cold Cold," and Pillar's "Bring Me Down." Most recently VH1's Celebrity Paranormal Project filmed there for the third episode of the series (titled "The Warden") as well as the last episode of the first season (titled "Dead Man Walking"). The prison was referred to as "The Walls Maximum Security Prison" in both episodes to protect the location's privacy.

Gallery

Abandoned cell block

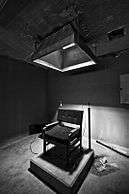

Abandoned cell block Remains of the electric chair chamber

Remains of the electric chair chamber Typical cell facilities

Typical cell facilities

References

- Tennessee Department of Corrections. "Tennessee State Penitentiary". Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- Sims, Elizabeth (3 March 2020). "Historic Tennessee State Prison damaged in Nashville tornadoes". WBIR.

- Thompson, E. Bruce (1942). "Reforms in the Penal System of Tennessee, 1820-1850". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 1 (4): 291–308. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42621720.

- "Tennessee State Prison Records 1831-1992" (PDF).

- Kurshan, Nancy. "Women and imprisonment in the U.S.: History and Current Reality" (PDF).

External links

- Tennessee State Penitentiary at Abandoned

- Tennessee State Prison at IMDb