Cummins Unit

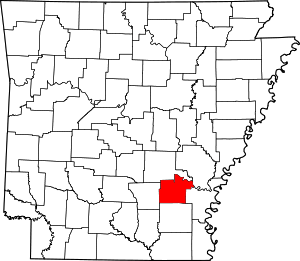

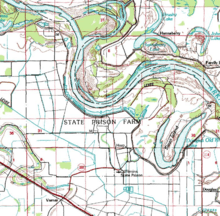

The Cummins Unit (formerly known as Cummins State Farm) is an Arkansas Department of Correction prison in unincorporated Lincoln County, Arkansas, United States,[3] in the Arkansas Delta region.[4] It is located along U.S. Route 65,[3] near Grady,[3] Gould,[5] and Varner,[6] 28 miles (45 km) south of Pine Bluff,[3] and 60 miles (97 km) southeast of Little Rock.[7][8]

Cummins | |

|---|---|

Cummins Unit | |

Cummins Location within the state of Arkansas | |

| Coordinates: 34°03′05″N 91°35′02″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arkansas |

| County | Lincoln |

| Township | Auburn Township |

| Elevation | 177 ft (54 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 71644 |

| Area code(s) | 870 |

| GNIS feature ID | 64050[1] GNIS for prison building: 82008[2] |

This prison farm is a 16,500-acre (6,700 ha) correctional facility. The prison first opened in 1902 and has a capacity of 1,725 inmates. Cummins housed Arkansas's male death row until 1986, when it was transferred first to the Tucker Maximum Security Unit. The State of Arkansas execution chamber is located in the Cummins Unit, adjacent to the location of the male death row, the Varner Unit.[9] The female death row is located at the McPherson Unit.[10] Cummins is one of the state of Arkansas's "parent units" for male prisoners; it serves as one of several units of initial assignment for processed male prisoners.[11]

History

In 1902 the State of Arkansas purchased about 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) of land for $140,000 ($4137000 when adjusted for inflation) to build the Cummins Unit.[12] The prison was established during that year,[13] and prisoners began occupying the site in December.[14] The prison occupied the former Cummins and Maple Grove plantations.[15]

Then-Governor of Arkansas Jeff Davis wanted the state to buy a farm in Jefferson County owned by Louis Altheimer, a Republican Party leader who was Davis's friend. When the legislature instead purchased the land for Cummins, Davis put up political opposition, trying to force the state to cancel the purchase.[16]

In 1933 Governor Junius Marion Futrell closed the Arkansas State Penitentiary ("The Walls"), and some prisoners moved to Cummins from the former penitentiary.[12] Since the establishment of the prison, it had housed African-American men and women. Beginning in 1936, White male prisoners with disciplinary problems were housed at Cummins. As of 1958, most prisoners worked in farming, producing cotton, livestock, and vegetables. The prison, during that year, housed clothing and lumber manufacturing facilities.[17] In 1951 White female prisoners were moved from the Arkansas State Farm for Women to Cummins.[18]

On September 5, 1966, riots occurred at Cummins. 144 prisoners attempted a strike, and Arkansas State Police ended the strike with tear gas.[19] In 1970 some prisoners asking for segregated housing started a riot, leading to the intervention of state police.[20]

In 1969 Johnny Cash performed at a concert in Cummins Unit. He donated his own money so a chapel could be built there.[21]

In 1972 Arkansas's first prison rodeo was held at the Cummins Unit.[12] In 1974 death row inmates, previously at the Tucker Unit, were moved to the Cummins Unit.[22] In 1976 female inmates were moved from the Cummins Unit to the Pine Bluff Unit. In 1978 a new execution chamber opened at Cummins Unit.[12] In 1983 the Cummins Modular Unit opened.[23] In 1986 death row inmates were moved to the Maximum Security Unit.[22] In 1991 the vocational technology program moved from the Cummins Unit to the Varner Unit.[24] In 2000 Arkansas's first lethal electrified fence, built with inmate labor, opened at the Cummins Unit.[12]

A tornado affected the Cummins Unit facility in May 2011. It damaged the dairy facility, the chicken and swine houses, and the employee housing in the Free Line area. The tornado destroyed the prison's three green houses. It also turned over a center pivot irrigation system.[25]

Torture

In 1968, Tom Murton alleged that three human skeletons found on the farm were the remains of inmates who had been subjected to torture, prompting a publicized investigation which found "a prison hospital served as torture chamber and a doctor as chief tormentor."[26]

The revelations included allegations of electrical devices connected to the genitalia of inmates. The Arkansas State Penitentiary System at that time had already been found to have held inmates at the Cummins Unit under conditions rising to the level of unconstitutionally cruel and unusual punishment, in cases tried by the US District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas, among others.

"Certain characteristics of the Arkansas prison system serve to distinguish it from most other penal institutions in this country. First, it has very few paid employees; armed trusties ["trusted" inmates, according to the source] guard rank and file inmates and trusties perform other tasks usually and more properly performed by civilian or "free world" personnel. Second, convicts not in isolation are confined when not working, and are required to sleep at night in open dormitory type barracks in which rows of beds are arranged side by side; there are large numbers of men in each barracks. Third, there is no meaningful program of rehabilitation whatever at Cummins; while there is a promising and helpful program at Tucker, it is still minimal."[27]

Composition

Cummins has about 16,500 acres (6,700 ha) of land.[13]

A white building is and has been referred to the past as the prison's "barracks." The "telephone-pole" style structure serves as a housing unit for prisoners. The building had eight units. In the past, one was reserved for White trustees, one for Black trustees, and others for other prisoners. The housing units were racially segregated.[28]

The prison includes the "Free Line," the prison residences for free world employees, including the warden, several prison officials, and their families; prisoners work as house servants in the Free Line.[8] Children living on the prison property are zoned to the Dumas School District.[29][30]

In the past the main entrance to the prison was at the terminus of a road off of the main highway. The main gate consisted of a wooden structure behind a chicken wire fence, which had barbed wire on top. A trusty shooter manned the main entrance.[8] In past eras, the prison housed a commissary and did not house educational facilities, prison factories, or medical and dental clinics.[28]

The Cummins Unit has an electric fence.[31]

The Cummins/Varner Volunteer Fire Department provides fire services to the Cummins Unit property.[32] The station is inside the Cummins Unit property,[33] along Arkansas Highway 388.[34] In the financial year 2010 the Arkansas Department of Correction spent $81,691 on the fire station.[33]

Operations

As of 2006, the Cummins Unit has the largest farming operation in the Arkansas Department of Correction system. At Cummins, over 16,000 acres (6,500 ha) of land is devoted to production of crops and farm goods, including cash crops, hay, livestock, and vegetables.[35] As of 2001 prisoners harvest corn, cotton, and rice from the fields and are supervised by prison guards mounted on horses.[4]

Cummins previously housed the Special Management Barracks, a unit for prisoners with counseling and mental health requirements.[36] In 2008 it moved to the Randall L. Williams Correctional Facility.[37]

Prisoners at Cummins attend the correctional school system.[38]

Prisoner life

In the past, each prisoner worked for 10 hours per day, six days per week in the fields. Prisoners were only excused if the outside temperature was below freezing.[8] Some prisoners who were sent to the fields lacked shoes.[39] Prisoners did not have fixed quotas. Instead they were told to do as much work as possible. Prisoners deemed to be not doing enough work were beaten.[28]

Trustee prisoners had authority over other prisoners. At night, all except for two of the free world prison guards left, so trustees kept the order during the night. Prisoners who were not trustees were sub-ranked as "do-pops" and "rankers."[28] In past eras, trustee prisoners were responsible for the institution's perimeter security.[8]

During the day, the prison barracks were empty since most prisoners worked on the fields. At night, the two free world employees patrolled the central corridor but did not venture into the barrack units. The trustees, armed with knives, kept the order at night. Some inmates, referred to as "crawlers" and "creepers," stabbed sleeping prisoners. Male on male rape frequently occurred in the housing units. The prison did not ask trustees to intervene in case of rape, and prison guards rarely intervened.[28]

Prisoners did not receive payment for working in the fields. In order to buy items from the commissary, some prisoners worked there.[28] Other prisoners sold their blood; a healthy prisoner was permitted to sell his blood once weekly.[40]

Trustees were allowed to leave and re-enter the prison without undergoing searches, so trustees smuggled in alcohol, illegal drugs, and weapons; they then sold those items within the prison. Trustees usually bought these items from one another, since they had large amounts of money. Non-trustees, including "do-pops" and "rankers," had to pay trustees in order to get food, medicine, access to medical staff, access to outsiders, and protection from arbitrary prison punishments. Therefore non-trustees did not have large reserves of extra money.[40]

Education in the Cummins Unit began in 1968, when the Gould School District started a night program.[41]

Wardens

- Terrell Don Hutto (1967-?) T. Don Hutto[42][43][44][45]

Bruce Jackson's prison photography

In the 1960s, ethnographer Bruce Jackson began taking photographs of prisoners for his research on African American work songs in prison. Jackson had become friends with the assistant warden at the time, T. Don Hutto, and their friendship provided Jackson with access to prisoners resulting in numerous publications. In 2010, Jackson's photo collection from the Cummins Unit was exhibited at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.[46][45]

See also

References

- General

- The Shame of the Prisons (Time magazine)

- New Chapter in Horror (The Nation, National Digital Archive)

- One Year of Prison Reform (The Nation, National Digital Archive)

- Arkansas Department of Correction: Prison History

- "Prisons: Hell in Arkansas." TIME. Friday February 9, 1968.

- Factor 8: The Arkansas Prison Blood Scandal Movie Factor 8: The Arkansas Prison Blood Scandal

- Bruce Jackson, Killing Time: Life in the Arkansas Penitentiary. Cornell University Press, 1977

- Specific

- "Cummins, Arkansas". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Cummins State Prison". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Cummins Unit." Arkansas Department of Correction. Retrieved on August 15, 2010. Archived July 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Nelson, Melissa. "http://thecabin.net/stories/120901/sta_1209010063.shtml Inmates recall prison life before reforms at harsh Cummins Unit." (Archive) Associated Press at the Log Cabin Democrat. Sunday December 9, 2001. Retrieved on June 3, 2013.

- Barnes, Royl S. Facts, Figures, and Functions of Arkansas State and Local Government. Hurley Co., 1957. 182. Retrieved from Google Books on March 6, 2011. "Arkansas maintains three penitentiary units: the Women's Reformatory at Cummins near Gould; one near Tucker for white men, known as the Tucker Farm; and the other near Gould, for Negro men and women, known as the Cummins Farm."

- "Arkansas killer plans no more appeals He is to die Wednesday in '84 death of trooper." Associated Press at The Dallas Morning News. April 18, 1995. Retrieved on March 5, 2011. "[...] and he was transferred to the death watch cell at the Cummins Unit near Varner."

- "Over 20 Convicts Flee State Farm." The Day. Thursday Afternoon January 20, 1916 (35th Year). 1. Retrieved from Google News (1 of 14) on March 5, 2011.

- Feeley, Malcolm M. and Edward L. Rubin. Judicial Policy Making and the Modern State: How the Courts Reformed America's Prisons. Cambridge University Press, 2000. 53. Retrieved from Google Books on March 5, 2011. ISBN 0-521-77734-8, ISBN 978-0-521-77734-6

- "State Capitol Week in Review." State of Arkansas. June 13, 2008. Retrieved on August 15, 2010. "Executions are carried out in the Cummins Unit, which is adjacent to Varner."

- Haddigan, Michael. "They Kill Women, Don't They?" Arkansas Times. April 9, 1999. Retrieved on August 15, 2010.

- "Guide for Family and Friends Archived August 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 2 (4/27). Retrieved on July 18, 2010.

- "Prison History and Gallery Archived 2011-03-10 at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. Retrieved on September 7, 2010.

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 14 (14/28). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 23 (23/28). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- The Southwestern Reporter. West Publishing Company, 1911. Volume 136. Retrieved from Google Books on September 23, 2011. 663.

- Donovan, Timothy Paul and Willard B. Gatewood. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. University of Arkansas Press, 1995. 125. Retrieved from Google Books on March 5, 2011. ISBN 1-55728-331-1, ISBN 978-1-55728-331-3.

- Federal Writers' Project. Arkansas: A Guide to the State. US History Publishers, 1958. 277. Retrieved from Google Books on March 5, 2011. ISBN 1-60354-004-0, ISBN 978-1-60354-004-9

- "Prison History and Gallery Archived 2011-03-10 at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Corrections. Retrieved on March 5, 2011.

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 24 (24/28). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 25 (25/28). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "Johnny Cash and the Forgotten Prison Blues." BBC. Monday January 7, 2013.

- "2006 Facts Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. July 1, 2005-June 30, 2006. 25 (25/38). Retrieved on August 15, 2010.

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 26 (26/28). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 27 (27/28). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "2012 Billy Max Moore Award Winner: David L. Allen." (Archive) The Advocate. Arkansas Department of Correction. December 2012. p. 9. Retrieved on April 16, 2013. "In May 2011, a tornado hit the Cummins Farm, devastating the employees‘ free line housing, dairy facility, swine and chicken houses; turning over a center pivot irrigation system; and completely destroying three green houses."

- von Zielbauer, Paul and Joseph Plambeck. "As Health Care in Jails Goes Private, 10 Days Can Be a Death Sentence." The New York Times. February 27, 2005. 4. Retrieved on July 11, 2010.

- "Holt v. Sarver". U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas. Max Pages. 1970. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- Feeley, Malcolm M. and Edward L. Rubin. Judicial Policy Making and the Modern State: How the Courts Reformed America's Prisons. Cambridge University Press, 2000. 54. Retrieved from Google Books on March 5, 2011. ISBN 0-521-77734-8, ISBN 978-0-521-77734-6

- "Maintenance & Transportation Department Archived August 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Dumas School District. Retrieved on March 6, 2011.

- "ARKANSAS SCHOOL DISTRICTS AND EDUCATION COOPERATIVES EFFECTIVE JULY 1, 2010." (Archive) Arkansas Department of Education. Retrieved on March 7, 2011.

- "Third Electric Fence Installed With Inmate Labor." ADC Advocate. Arkansas Department of Correction, February 2005. 3 (3/25). Retrieved on March 6, 2011.

- "Fire Department Ratings." Fox 16. Retrieved on March 5, 2011.

- "Annual Report Financial Year 2010." Arkansas Department of Correction. 3/6. Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "Cummings Volunteer Fire Station." [sic] United States Geological Survey. Retrieved on May 5, 2011. "State Highway 388, Grady, Ar 71644"

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 8 (8/38). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "2006 Fact Brochure Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Correction. 36 (36/38). Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "ADC Acquires Jefferson County Jail." Financial Year 2008 Annual Report. (Archive) Arkansas Department of Correction. Retrieved on March 8, 2011.

- "SCHOOL/DISTRICT Archived 2011-10-11 at the Wayback Machine." Arkansas Department of Education. Retrieved on September 23, 2011.

- Feeley, Malcolm M. and Edward L. Rubin. Judicial Policy Making and the Modern State: How the Courts Reformed America's Prisons. Cambridge University Press, 2000. 53-54. Retrieved from Google Books on March 5, 2011. ISBN 0-521-77734-8, ISBN 978-0-521-77734-6

- Feeley, Malcolm M. and Edward L. Rubin. Judicial Policy Making and the Modern State: How the Courts Reformed America's Prisons. Cambridge University Press, 2000. 55. Retrieved from Google Books on March 5, 2011. ISBN 0-521-77734-8, ISBN 978-0-521-77734-6

- "History And Description Of The Arkansas Correctional School." Arkansas Correctional School. Retrieved on March 7, 2011.

- Bauer, Shane (2018). "The Straight Line From Slavery to Private Prisons: How Texas Turned Plantations into Prisons". Literary Hub. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Bauer, Shane (September 18, 2018). American Prison: a Reporter's Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 368. ISBN 978-0735223585.

- "Shockingly Candid Photos Of Life on a 1970s Arkansas Prison Farm: "Just about everyone carrying a gun was a convict"". Mother Jones. August 9, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2018. Photography by Bruce Jackson

- Estrin, James (May 27, 2009). "Showcase: A Wide View of a Hellish World". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- Kurutz, Steven (September 4, 2010). "Speakeasy: Bruce Jackson on how he became the dean of prison folklore". Wall Street Journal.

External links

- Cummins Unit, from the Arkansas Department of Corrections

- "Cummins Unit" entry from the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

- "Demonstration of In-Vessel Composting Cummins Unit Arkansas Department of Correction Pine Bluff, Arkansas." Texas A&M University Commerce