Templum Domini

The Templum Domini[2][3] (Vulgate translation of Hebrew: 'הֵיכָל ה "Temple of the Lord") was the name attributed by the Crusaders to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.[4] It became an important symbol of Jerusalem, depicted on coins minted under the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The Dome of the Rock was erected in the late 7th century under the 5th Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan at the site of the former Jewish Second Temple (or possibly added to an existing Byzantine building dating to the reign of Heraclius, 610–641).[5] After the capture of Jerusalem in the First Crusade (1099), the Dome of the Rock was given into the care of Augustinian Canons Regular, who turned it into a Christian church.

The adjacent Al-Aqsa Mosque was called Templum Solomonis ("Temple of Solomon") by the Crusaders. It first became a royal palace. The image of the Dome, as representing the "Temple of Solomon", became an important iconographic element in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The royal seals of the Kings of Jerusalem depicted the city symbolically by combining the Tower of David, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Dome of the Rock and the city walls.

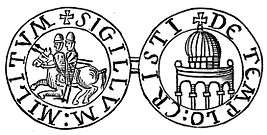

After the completion of the purpose-built royal palace near the Jaffa Gate, the King of Jerusalem gave the building to the Knights Templar, who maintained it as their headquarters. The Dome was indicated on the reverse of the seals of the Grand Masters of the Knights Templar (such as Everard des Barres and Renaud de Vichiers), and it became the architectural model for round Templar churches across Europe.[6]

Although the adjacent Dome of the Ascension was constructed as a baptistry during the Crusader period, it has since remained in the hands of Islamic authorities as part of the larger complex of the Dome of the Rock.[7][8]

See also

- History of Jerusalem during the Crusader period

References

- Drawing from T. A. Archer, The Crusades: The Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1894), p. 176. The design with the two knights on a horse and the inscription SIGILLVM MILITVM XRISTI is attested in 1191; see Jochen Burgtorf, The central convent of Hospitallers and Templars: history, organization, and personnel (1099/1120-1310), Volume 50 of History of warfare (2008), ISBN 978-90-04-16660-8, pp. 545–546.

- The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: Volume 3, The City of Jerusalem.

- Paul, Nicholas; Yeager, Suzanne (2012-03-02). Remembering the Crusades: Myth, Image, and Identity. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421406992.

- Jeffery, George (2010-10-31). A Brief Description of the Holy Sepulchre Jerusalem and Other Christian Churches in the Holy City: With Some Account of the Mediaeval Copies of the Holy Sepulchre Surviving in Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108016049.

- H. Busse, "Zur Geschichte und Deutung der frühislamischen Ḥarambauten in Jerusalem", Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 107 (1991), 144–154. (gere 145f).

- The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance, Jacob Burckhardt, Peter Murray, James C. Palmes, University of Chicago Press, 1986, p. 81

- Prawer, Jonathan (1996). The History of Jerusalem: The Early Muslim Period (638–1099). New York University Press. p. 86. ISBN 0814766390.

- Simon Sebag Montefiore, Jerusalem: The Biography, p. 276.