Tempio Malatestiano

The Tempio Malatestiano (Italian Malatesta Temple) is the unfinished cathedral church of Rimini, Italy. Officially named for St. Francis, it takes the popular name from Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, who commissioned its reconstruction by the famous Renaissance theorist and architect Leon Battista Alberti around 1450.[1]

| Tempio Malatestiano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| District | Diocese of Rimini |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica |

| Year consecrated | 800 |

| Location | |

| Location | |

| Geographic coordinates | 44°03′35″N 12°34′13″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Leon Battista Alberti |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 800 |

| Completed | 1468 (unfinished) |

History

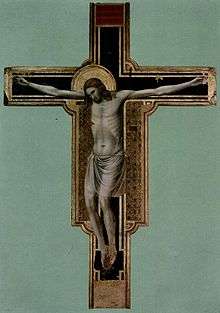

San Francesco was originally a thirteenth-century Gothic church belonging to the Franciscans. The original church had a rectangular plan without side chapels, with a single nave ending with three apses. The central one was probably frescoed by Giotto, to whom is also attributed the crucifix now housed in the second right chapel.

Malatesta called on Alberti, as his first ecclesiastical architectural work, to transform the building and make it into a kind of personal mausoleum for him and his lover and later his wife, Isotta degli Atti. The execution of the project was handed over to the Veronese Matteo di Andrea de' Pasti, hired at the Estense court. Of Alberti's project, the dome that appears in Matteo's foundation medal of 1450—similar to that of the Pantheon of Rome and intended to be among the largest in Italy—was never built. Also the upper part of the façade, which was supposed to include a gable end, was never finished, though it had risen to a considerable height by the winter of 1454, as Malatesta's fortunes declined steeply after his excommunication in 1460 and the structure remained as we see it, with its unexecuted east end, at his death in 1466. The two blind arcades at the side of the entrance arch were to house the sarcophagi of Sigismondo Pandolfo and Isotta, which instead are now in the interior.

Works for the renovation of the nave began some five years before those of the exterior shell that encases the church. Marble for the work was taken from the Roman ruins in Sant'Apollinare in Classe (near Ravenna) and in Fano.

Overview

The church is immediately recognizable from its wide marble façade, decorated by sculptures probably made by Agostino di Duccio and Matteo de' Pasti. Alberti aspired to renew and rival the Roman structures of antiquity, though here his inspiration was drawn from the triumphal arch,[2] in which his main inspiration was the tripartite Arch of Constantine in Rome. But as Rudolf Wittkower remarked,[3] he drew details (the base, the half-columns, the discs, moldings) from the Arch of Augustus. The large arcades on the sides are reminiscent of the Roman aqueducts. In each blind arch is a sarcophagus, a gothic tradition of interment under the exterior side arches of a church.[4]

The entrance portal has a triangular pediment over the door set within the center arch; geometrical decorations fill the tympanum. In the interior, where Matteo de' Pasti took credit as architect in an inscription, under the large arcades on the right side, are seven chapels with the tombs of illustrious Riminese citizens, including that of the philosopher Gemistus Pletho, whose remains were brought back by Sigismondo Pandolfo from his wars in the Balkans. The left side has no chapels (outside is a 16th-century bell tower).

Immediately right of the main door is Sigismondo Pandolfo's sepulchre. The next chapel is dedicated to St. Sigismund, patron of soldiers (Sigismondo Pandolfo was a renowned condottiero), and has fine sculptures by Agostino di Duccio. There is also a fresco by Piero della Francesca portraying Malatesta kneeling before the saint (1451). The following chapel (Cappella degli Angeli) houses the tomb of Isotta and the Giotto crucifix, allegedly painted during his sojourn in Rimini of 1308-1312.

The next chapel is the Cappella dei Pianeti ("Chapel of the Planets"), dedicated to St. Jerome. The zodiacal figures are by Agostino di Duccio. It houses also an interesting panorama of Rimini as it was in the 15th century. Then comes the Chapel of Liberal Arts, with di Duccio's portrayal of Philosophy, Rhetoric and Grammar. The subsequent Chapel of the Childhood Games houses the tombs of Sigismondo Pandolfo's first wives, Ginevra d'Este and Polissena Sforza, encircled by 61 figures of young angels playing and dancing, again by Agostino di Duccio.

The bodies of some of Malatesta's ancestors are housed in the Cappella della Pietà, with two statues of prophets and ten of sibyls. The chapel, like numerous other places in the church, is characterized by the presence of the SI monogram (from the initial of Sigismondo and Isotta's names, or, according to others, the first two letters of the former) sporting a rose, an elephant and three heads.

Evaluation

Due to the strong presence of elements referring to the Malatesta's history, and to Sigismondo Pandolfo himself (in particular, his lover Isotta), the church was considered by some contemporaries to be an exaltation of Paganism. Pope Pius II, Sigismondo's deadliest enemy, declared it as "full of pagan gods and profane things".[5]

Destruction and restoration

The church was heavily damaged during World War II, and afterward reconstructed using pieces salvaged from the rubble by men from the Allies-affiliated Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives unit.[6]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tempio Malatestiano. |

Sources

- Cricco, Giorgio; Francesco P. Di Teodoro (1996). Itinerario nell'arte. Bologna: Zanichelli. pp. 327–328.

References

- Corrado Ricci, Il Tempio Malatestiano (Milan) 1924, remains the standard monograph, supplemented by Cesare Brandi, Il Tempio Malatestiano (Turin) 1956. Sigismondo had begun modestly, with two chapels added to the interior, 1447-49.

- Alberti was not directly inspired here by pagan temples, as in his later Basilica di Sant'Andrea in Mantua.

- Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of humanism (1962) 1965:37 note 3.

- As Ricci pointed out, Ricci 1924:281ff.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2006-10-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- How the Monuments Men Saved Italy’s Treasures Smithsonian magazine