Takrur

Takrur, Tekrur or Tekrour (c. 800 – c. 1285) was an ancient state of West Africa, which flourished roughly parallel to the Ghana Empire.

Takrur | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800s–1285 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Settlement on Morfil | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Serer,[1][2] Fula | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam, Traditional African religions (Serer religion[3][4]) | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

• 1030s | War Jabi | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 800s | ||||||||||||||

• Islam | 1030s | ||||||||||||||

• Conquered by Mali Empire | 1285 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Senegal |

|

|

|

|

Origin

Takrur was the capital of the state which flourished on the lower Senegal River. Takruri was a term, like Bilad-ul-Sudan, that was used to refer to all people of West African ancestry,[5][6] and is still in use as such in the Middle East, with some corruption, as in Takruni, pl. Takarna تكروني in Saudi Arabia. The district of Bulaq Al-Dakrur بولاق الدكرور in Cairo is named after an ascetic from West Africa.

The formation of the state may have taken place as an influx of Fulani from the east settled in the Senegal valley.[7][8] John Donnelly Fage suggests that Takrur was formed through the interaction of Berbers from the Sahara and "Negro agricultural peoples" who were "essentially Serer".[9]

Centre of trade

Located in the Senegal valley, along the border of present-day Senegal and Mauritania, it was a trading centre, where gold from the Bambuk region,[10] salt from the Awlil,[11] and Sahel grain were exchanged. It was rival of the Ghana Empire, and the two states clashed from occasionally with the Soninké, usually winning. Despite these clashes, Takrur prospered throughout the 9th and 10th centuries.

According to Levtzion, "It is significant that the cotton tree and the manufacture of cloth were first reported from Takrur."[10]:179

Adoption of Islam

The kings of Takrur eventually adopted Islam. Sometime in the 1030s during the reign of king War Jabi, the court converted to Islam, the first regent to officially pronounce orthodoxy in the Sahel, establishing the faith in the region for centuries to come. In 1035 that War Jabi introduced Sharia law in the kingdom. This adoption of Islam greatly benefited the state economically and created greater political ties that would also affect them in the coming conflicts between the traditionalist state of Ghana and its northern neighbours.[12]

Ghana Empire

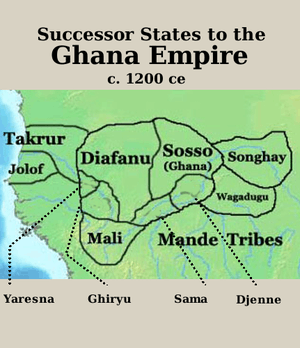

The Fulani of Takrur became independent after Ghanaian power faded. Takrur in turn set out to conquer the Kingdom of Diara, which was a Ghanaian province before. Then in 1203, Takrur leader Sumanguru took control of Kumbi Saleh, the capital of Ghana. Thus, Takrur became the sole power in the region.[13]

Downfall

Among these were the Susu who carved out the sizeable though short-lived Kaniaga. Waalo, the first Wolof state, emerged out its south. By the time Mandinka tribes united to form the Mali Empire in 1235, Takrur was in a steep decline. The state was finally conquered by the usurper emperor Sabakoura of Mali in the 1280s.

Takrur was later conquered by Mali; it was also conquered by Jolof in the 15th century.[14] However, Koli (a Fula rebel) did finally manage to regain Takrur, and named it Fouta Toro in the 15th century, thereby setting up the first Fula dynasty (Denanke). This dynasty also did not last and in 1776 during the Fouta Revolution, led by Muslim clerics, the kingdom was entered and the house of Denanke was brought down.[15]

Takrur as toponym

After the fall of Takrur its name was employed by Arab historians as a synonym for "West Africa". In the Middle East west Africans are still referred to as Tukrir to this day.[16]

See also

Notes

- Charles Becker et Victor Martin, « Rites de sépultures préislamiques au Sénégal et vestiges protohistoriques », Archives Suisses d'Anthropologie Générale, Imprimerie du Journal de Genève, Genève, 1982, tome 46, no 2, p. 261-293

- Trimingham, John Spencer, "A history of Islam in West Africa", pp 174, 176 & 234, Oxford University Press, USA (1970)

- Becker

- Gravrand, "Pangool", pp 9, 20-77

- 'Umar Al-Naqar (1969). "Takrur the History of a Name". The Journal of African History. 10 (3): 365–374. doi:10.1017/s002185370003632x. JSTOR 179671.

- Ibn Khalikan, op. cit. vi, 14.

- Hrbek, I. (1992). General History of Africa volume 3: Africa from the 7th to the 11th Century: Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century v. 3 (Unesco General History of Africa (abridged)). James Carey. p. 67. ISBN 978-0852550939.

- Creevey, Lucy (August 1996). "Islam, Women and the Role of the State in Senegal". Journal of Religion in Africa. 26 (3): 268–307. doi:10.1163/157006696x00299. JSTOR 1581646.

- Fage, John Donnelly (1997). "Upper and Lower Guinea". In Roland Oliver (ed.). The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521209816.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. New York: Methuen & Co Ltd. p. 44. ISBN 0841904316.

- Shillington, Kevin (2012). History of Africa. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 94. ISBN 9780230308473.

- Robinson, David (12 January 2004). Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53366-9. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Davidson, Basil (1965). A History of West Africa (PDF). University of Lagos, Nigeria: Longman. ISBN 0684826674.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leyti, Oumar Ndiaye. Le Djoloff et ses Bourba. Nouvelles Editions Africaines, 1981. ISBN 2-7236-0817-4

- Ogot, Bethwell A. General history of Africa: Africa from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-06700-2, p 146

- Smidt 2010, p. 998.

Sources

- J. F. Ade Ajayi, Michael Crowder (eds.). History of West Africa. Columbia University (1972) ISBN 0-231-03628-0

- J. Hunwick. "Takrur", Encyclopaedia of Islam, Leiden 2000, X, 142–3.

- Mary Antin, Nehemia Levtzion. Medieval West Africa Before 1400: Ghana, Takrur, Gao (Songhay) and Mali. Translated by Nehemia Levtzion. J. F. Hopkins: Contributor. Markus Wiener Publishing, New Jersey (1998). ISBN 1-55876-165-9

- J. D. Fage (ed.). The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. II, Cambridge University Press (1978), 675–7.

- H. T. Norris. "The Wind of Change in the Western Sahara". The Geographical Journal, Vol. 130, No. 1 (Mar., 1964), pp. 1–14

- D.W. Phillipson. African Archaeology, Cambridge University Press (Revised Edition 2005). ISBN 978-0-521-83236-6

- Leyti, Oumar Ndiaye. Le Djoloff et ses Bourba. Nouvelles Editions Africaines, 1981. ISBN 2-7236-0817-4

- Ogot, Bethwell A. General history of Africa: Africa from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-06700-2, p 146.

- Oliver, Roland. The Cambridge history of Africa: From c. 1600 to c. 1790. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-521-20981-1, p484

- Smidt, Wolbert (2010). "Tukrir". In Siegbert Uhlig, Alessandro Bausi (ed.). Encyclopedia Aethiopica. 4. Harrassowitz. pp. 998–1000. ISBN 9783447062466.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- McIntosh, Roderick J.; McIntosh, Susan Keech; Bocoum, Hamady (2016). The Search for Takrur: Archaeological Excavations and Reconnaissance Along the Middle Senegal Valley. The Yale Peabody Museum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)