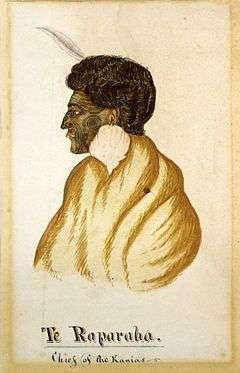

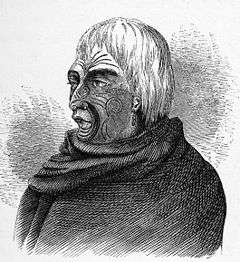

Te Rauparaha

Te Rauparaha (1760s – 27 November 1849)[1] was a Māori rangatira (chief) and war leader of the Ngāti Toa tribe who took a leading part in the Musket Wars. He was influential in the original sale of land to the New Zealand Company and was a participant in the Wairau Affray in Marlborough.

Te Rauparaha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1760s |

| Died | 27 November 1849 |

| Allegiance | Ngāti Toa |

| Years of service | 1819-1848 |

| Battles/wars | |

Early days

From 1807, muskets became the weapon of choice and partly changed the character of tribal warfare. In 1819 Te Rauparaha joined with a large war party of Ngāpuhi led by Tāmati Wāka Nene; they probably reached Cook Strait before turning back.

Migration

Over the next few years the intertribal fighting intensified, and by 1822 Ngāti Toa and related tribes were being forced out of their land around Kāwhia after years of fighting with various Waikato tribes often led by Te Wherowhero. Led by Te Rauparaha they began a fighting retreat or migration southwards (this migration was called Te-Heke-Tahu-Tahu-ahi), conquering hapu and iwi as they went south. This campaign ended with Ngāti Toa controlling the southern part of the North Island and particularly the strategically placed Kapiti Island, which became the tribal stronghold for a period.[2]

In 1824 an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 warriors comprising a coalition of tribes from the East Coast, Whanganui, the Horowhenua, southern Taranaki[3] and Te Wai Pounamu (the South Island) assembled at Waikanae, with the object of taking Kapiti Island. Crossing in a flotilla of war canoes under cover of darkness, they were met as they disembarked by a force of Ngāti Toa fighters led or reinforced by Te Rauparaha. The ensuing Battle of Waiorua, at the northern end of the island, ended with the rout and slaughter of the landing attackers who were disadvantaged by difficult terrain and weather plus divided leadership.[4] This decisive victory left Te Rauparaha and the Ngāti Toa able to dominate Kapiti and the adjacent mainland.[4]

Trade and further conquest

Following the Battle of Waiorua, Te Rauparaha began a series of almost annual campaigns into the South Island with the object in part of seizing the sources of the valuable mineral greenstone. Between 1827 and 1831 he was able to extend the control of Ngati Toa and their allies over the northern part of the Southern Island.[5] His base for these sea-based raids remained Kapiti.

During this period Pākehā whaling stations became established in the region with Te Rauparaha's encouragement and the participation of many Māori. Some Māori women married Pākehā whalers and a lucrative two-way trade of supplies for muskets was established, thereby increasing Te Rauparaha's mana and military strength. By the early 1830s Te Rauparaha had defeated a branch of the Rangitane iwi in the Wairau Valley and gained control over that area. Te Rauparaha married his daughter Te Rongo to an influential whaling captain Captain John William Dundas Blenkinsop to whom he sold land in the Wairau Valley for a whaling station. It is uncertain if Te Rauparaha understood the full implications of the deed of sale that he signed and gave to the captain.

Te Rauparaha then hired the brig Elizabeth, captained by John Stewart, to transport himself and approximately 100 warriors to Akaroa Harbour with the aim of attacking the local tribe, the Ngai Tahu.[6] Hidden below deck Te Rauparaha and his men captured the Ngai Tahu chieftain Tamaiharanui, his wife and daughter when they boarded the brig at Stewart's invitation. Several hundred of the Ngai Tahu were killed both on the Elizabeth and during a surprise landing the next morning. During the voyage back to Kapiti the chief strangled his own daughter Nga Roimata, apparently to save her from expected abuse.[7] Te Rauparaha was incensed and following their arrival at Kapiti the parents and other prisoners were killed, Tamaiharanui after prolonged torture.[8]

In 1831 he took the major Ngāi Tahu pā at Kaiapoi after a three-month siege , and shortly after took Onawe Pā in the Akaroa harbour, but these and other battles in the south were in the nature of revenge (utu) raids rather than for control of territory. Further conquests to the south were brought to a halt by a severe outbreak of measles and the growing strength of the southern hapu who worked closely with the growing European whaling community in coastal Otago and at Bluff.

European settlement

The last years of Te Rauparaha's life saw the most dramatic changes. On 16 October 1839 the New Zealand Company expedition commanded by Col William Wakefield arrived at Kapiti. They were seeking to buy vast areas of land with a view to forming a permanent European settlement. Te Rauparaha sold them some land in the area that became known later as Nelson and Golden Bay.

Te Rauparaha had requested that Rev. Henry Williams send a missionary and in November 1839 Octavius Hadfield travelled with Henry Williams, and Hadfield established an Anglican mission on the Kapiti Coast.[9]

Te Rauparaha provided the materials and labour for the construction of Rangiātea (completed in 1851), which began a revolution of aroha (love) and rangimarie (peace) on the Kapiti Coast. Iwi stopped fighting other iwi, kai tangata (cannibalism) and slavery ended, and an honourable way was found out of utu (vengeance).[10]

On 14 May 1840 Te Rauparaha signed a copy of the Treaty of Waitangi, believing that the treaty would guarantee him and his allies the possession of territories gained by conquest over the previous 18 years. On 19 June of that year, he signed another copy of the treaty, when Major Thomas Bunbury insisted that he do so (Oliver 2007).

Te Rauparaha soon became alarmed at the flood of British settlers and refused to sell any more of his land. This quickly led to tension and the upshot was the Wairau Affray when a party from Nelson tried to arrest Te Rauparaha, and 22 of them were killed when they fired upon Te Rauparaha and his people out of fear. The subsequent government enquiry exonerated Te Rauparaha which further angered the settlers who began a campaign to have the governor, Robert FitzRoy, recalled.

Capture and eventual death

Then in May 1846 fighting broke out in the Hutt Valley between the settlers and Te Rauparaha's nephew, Te Rangihaeata, another prominent Ngāti Toa war leader during the Musket Wars[11] Despite his declared neutrality, Te Rauparaha was arrested after the British captured secret letters from Te Rauparaha which showed he was playing a double game. He was charged with supplying weapons to Māori who were in open insurrection. He was captured near a tribal village Taupo Pa in what would later be called Plimmerton, by troops acting for the Governor, George Grey, and held without trial under martial law before being exiled to Auckland where he was held in the ship Calliope. His son, Tāmihana, was studying Christianity in Auckland and Te Rauparaha gave him a solemn message that their iwi should not take utu against the government. Tāmihana returned to his rohe to stop a planned uprising. Tāmihana sold the Wairau land to the government for 3,000 pounds.[1] Grey spoke to Te Rauparaha and persuaded him to give up all outstanding claims to land in the Wairau valley. Then, realising he was old and sick he allowed Te Rauparaha to return to his people at Ōtaki in 1848.

While in Ōtaki Te Rauparaha instigated the building of Rangiātea Church for his local pā. It would later become the oldest Māori church in the country and was known for its unique mix of Māori and English church design.[12] Te Rauparaha did not live to see the church completed and he died the following year on 27 November 1849.

Te Rauparaha's son Tāmihana was strongly influenced by missionary teaching,[13][14] especially Octavius Hadfield. He left for England in December 1850 and was presented to Queen Victoria in 1852. After his return he was one of the Māori to create the idea of a Māori king. However he broke away from the king movement and later became a harsh critic when the movement became involved with the Taranaki-based anti-government fighter Wiremu Kingi.[1]

Legacy

Te Rauparaha composed "Ka Mate" as a celebration of life over death after his lucky escape from pursuing enemies.[15][16] This haka or challenge, has become the most common performed by the All Blacks and many other New Zealand sports teams before international matches.

A biography of Te Rauparaha was published in the early 20th century. It was written by William Travers and was called the Stirring Times of Te Rauparaha.[17]

A memorial to Te Rauparaha was also established in Ōtaki. In June 2020, LifeNet charity director Brendan Malone called for the removal of Te Rauparaha's Ōtaki monument in response to calls in New Zealand and around the world to remove statues of controversial figures following the George Floyd protests since Te Rauparaha had enslaved, tortured, and eaten members of rival Māori tribes. In response, Victoria University of Wellington historian Dr Arini Loader and former Labour Party candidate Shane Te Pou disputed Malone's attempts to draw an analogy with colonial figures such as Captain John Fane Charles Hamilton, citing Te Rauparaha's support for a local church and arguing that other iwi including Rauparaha's former victims recognised his historical importance.[18]

References

- Oliver, Steven. "Te Rauparaha – Biography". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "The Church Missionary Gleaner, December 1851". The Contrast. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Chris Maclean, p.110, "Kapiti", ISBN 0-473-06166-X

- Chris Maclean, p.113, "Kapiti", ISBN 0-473-06166-X

- Chris Maclean, p.115 "Kapiti", ISBN 0-473-06166-X

- White, John (1890). The Ancient History of the Maori, His Mythology and Traditions: Tai-Nui [Vol VI]. Wellington: Government Printer, New Zealand Electronic Text Collection. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Chris Maclean, p.22 "Waikanae", ISBN 978-0-473-16597-0

- Chris Maclean, pp. 129–130 "Kapiti", ISBN 0-473-06166-X. The deaths of Tamaiharanui, his kindred and Nga Roimata are narrated in Alistair Campbell's poem Reflections on Some Great Chiefs

- "The Church Missionary Gleaner, March 1842". Remarkable Introduction and Rapid Extension of the Gospel in the Neighbourhood of Cook's Straits. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- "Taking down the fence: Waitangi Day at Rangiātea". Anglican Movement. 12 February 2020. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Musket Wars. R.Crosby, p.40 Reed. 1999

- "The Building of Rangiātea". National Library of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Stock, Eugene (1913). "The Story of the New Zealand Mission". Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "The Church Missionary Gleaner, April 1851". New-Zealand Chiefs in Committee Drawing Up a Reply to the Society's Jubilee Letter. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Pōmare, Mīria (12 February 2014). "Ngāti Toarangatira – Chant composed by Te Rauparaha". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Haka Ka Mate Attribution Act 2014 Guidelines" (PDF). Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Archived from the original (pdf) on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Travers, W.T. Locke (1906). The stirring times of Te Rauparaha (Chief of the Ngatitoa). Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Burrows, Matt (17 June 2020). "Te Rauparaha monument 'should remain in place' despite calls to tear it down, Māori historian says". Newshub. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

External links

![]()