Tandava

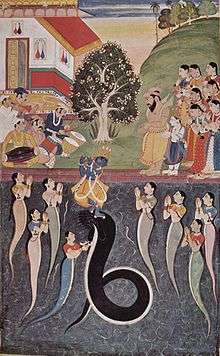

Tandava (also spelled as Tāṇḍavam) also known as Tāṇḍava natyam, is a divine dance performed by the Hindu gods. The Hindu scriptures narrate various occasions when gods have performed the Tandava. The Bhagavata Purana talks of Krishna dancing his Tandava on the head of the serpent Kaliya.[1] When Sati (first wife of Shiva, who was reborn as Parvati) jumped into the Agni Kunda (sacrificial fire) in Daksha's Yajna and gave up her life, Shiva is said to have performed the Rudra Tandava to express his grief and anger. Ganesha, the son of Shiva, is depicted as Ashtabhuja tandavsa nritya murtis (Eight armed form of Ganesha dancing the Tandava) in temple sculptures.[2]

According to Jain traditions, Indra is said to have performed the Tandava in honour of Rishabha (Jain tirthankar) on the latter's birth.[3]

Hinduism

Tandava, as performed in the sacred dance-drama of India, has vigorous, brisk movements. Performed with joy, the dance is called Ananda Tandava. Performed in a violent mood, the dance is called Raudra or Rudra Tandava. The types of Tandava found in the Hindu texts are: Ananda Tandava, Tripura Tandava, Sandhya Tandava, Samhara Tandava, Kali (Kalika) Tandava, Uma Tandava, Shiva Tandava, Krishna Tandava and Gauri Tandava.[4]

Krishna Tandava

According to Bhagavata Purana, Krishna danced on the hood of Kaliya, the serpent, subjugating him and cleansed the river Yamuna of its impurities. This episode describing the destruction of the venomous snake Kaliya, who was a menace to the people of Braj, is very popularly rendered as Krishna Tandava or Krishna's Tandava dance.[5]

Author Angana Jhaveri describes Krishna Tandava in the Raslila has very spritely and joyful dance movements. It involves small quick movements, light springly jumps, fast footwork, spinning at a dizzy speed and some acrobatic movements. But the overall effect of the form is that of grace and delicacy suitable to the romantic and youthful character of Krishna.[6]

Worship of Krishna as the "God of dance" is prevalent even before 16th centrury. Author and Professor Caleb Simmons in his book Devotional Sovereignty: Kingship and Religion in India says that, King Chikka Devaraja (the fourteenth maharaja of the Kingdom of Mysore) mindted a series of Gold coins called "Devaraja [with] the image of dancing Krishna" (tandava krishnamurti devaraja) to commemorate his coronation.[7]

Author Sehdev Kumar in his book A Thousand Petalled Lotus: Jain Temples of Rajasthan : Architecture & Iconography says that, Before 12th and 13th centuries, during the Chola period, Nataraja dancing and the Krishna dancing the tandava on the hood of hundred headed serpent kaliya, were favourite subjects for the artists.[8]

Scholar Lavanya Vemsani says, "Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi developed a style of dance known as Tandava, a set of vigorous dance moves mainly performed with brisk movements of the feet, which was once said to have been performed by the child Krishna while he deafeated the sepant Kaliya in Kalind lake in Brindavan".[9]

There are many composition where Krishna's Nritya (dance) is beautifully depicted. Purandara Dasa designates "Natya Krishna" also as "Tandava Krishna". Purandara Dasa in one of his compositions says, "Tandava krishnana bhajisi " ("Pray to Tandava Krishna"). Due to this reference we can note that 'tandava' also means a form of Nritya (dance) practised by Krishna and others.[10]

Shiva tandava & Shaivism

According to Shaivism, Shiva's Tandava is described as a vigorous dance that is the source of the cycle of creation, preservation and dissolution. While the Rudra Tandava depicts his violent nature, first as the creator and later as the destroyer of the universe, even of death itself, the Ananda Tandava depicts him as joyful. In Shaiva Siddhanta tradition, Shiva as Nataraja (lit. "King of dance"[11]) is considered to be supreme lord of dance.[12] The Tandavam takes its name from Tandu (taṇḍu), the attendant of Shiva, who instructed Bharata (author of the Natya Shastra) in the use of Angaharas and Karanas[13] modes of the Tandava at Shiva's order. Some scholars consider that Tandu himself must have been the author of an earlier work on the dramatic arts, which was incorporated into the Natya Shastra.[14] Indeed, the classical arts of dance, music and song may derive from the mudras and rituals of Shaiva tradition.

The 32 Angaharas and 108 Karanas are discussed by Bharata in the 4th chapter of the Natya Shastra, Tandava Lakshanam.[15] Karana is the combination of hand gestures with feet to form a dance posture. Angahara is composed of seven or more Karanas.[4]

"How many various dances of Shiva are known to His worshipers I cannot say. No doubt the root idea behind all of these dances is more or less one and the same, the manifestation of primal rhythmic energy. Whatever the origins of Shiva's dance, it became in time the clearest image of the activity of God which any art or religion can boast of." - Ananda Coomaraswamy[16]

The dance performed by Shiva's wife Parvati in response to Shiva's Tandava is known as Lasya, in which the movements are gentle, graceful and sometimes erotic. Some scholars consider Lasya to be the feminine version of Tandava. Lasya has 2 kinds, Jarita Lasya and Yauvaka Lasya.

Shiva Tandava Stotram is a stotra (Hindu hymn) that describes Shiva's power and beauty.

Indian classical dance

In Kathak dance three types of Tandavas are generally used, they are, Krishna Tandava, Shiva Tandava and Ravana Tandava, but sometimes a fourth variety - Kalika Tandava, is also often used.[17][18] The Manipuri dance is categorized as either "Tandava" (vigorous, usually go with Shiva, Shakti or Krishna as warrior-savior themed plays) or lasya (delicate,[19] usually go with love stories of Radha and Krishna).[20][21]

References

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande 1987, p. 98.

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande 1987, p. 5.

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande 1987, p. 146.

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande 1987, p. 154.

- Shovana Narayan (1 January 2004). Indian Theatre And Dance Traditions. Harman Publishing House. p. 14. ISBN 978-8186622612.

- Angana Jhaveri (1986). The Raslila Performance Tradition of Manipur in Northeast India. Michigan State University. Department of Theater. p. 105.

Krishna tandava as used in the raslila has very spritely and joyful dance movements. It involves small quick movements, light springy jumps, fast footwork, spinning at a dizzy speed and some acrobatic movements. But the overall effect of the form is that of grace and delicacy suitable to the romantic and youthful character of Krishna.

- Caleb Simmons (2 December 2019). Devotional Sovereignty: Kingship and Religion in India. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0190088910.

- Sehdev Kumar (2001). A Thousand Petalled Lotus: Jain Temples of Rajasthan : Architecture & Iconography. Abhinav Publications. p. 184. ISBN 978-8170173489.

- Lavanya Vemsani (13 June 2016). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Hindu Lord of Many Names: An Encyclopedia of the Hindu Lord of Many Names. ABC-CLIO. p. 220. ISBN 9781610692113.

Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi developed a style of dance known as Tandava, a set of vigorous dance moves mainly performed with brisk movements of the feet, which was once said to have been performed by the child Krishna while he deafeated the sepant Kaliya in Kalind lake in Brindavan.

- Tumuluri Seetharama Lakshmi (1994). A study of the compositions of Purandaradāsa and Tyāgarāja. Veda Sruti Publications. p. 116.

- Joyce Burkhalter Flueckiger (23 February 2015). Everyday Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 74. ISBN 978-1118528181.

- "Nataraja", Manas, UCLA

- Natya-shastra IV.263-264

- Quarterly Journal of the Andhra Historical Research Society, part III, pp. 25-26, as cited in Manohar Laxman Varadpande 1987, p. 154

- Ragini Devi, Dance Dialects of India, pp.29-30. Motilal Banarsidass (1990) ISBN 81-208-0674-3

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, "The Dance of Shiva", in The Dance of Shiva: Fourteen Indian Essays, rev. ed. (New York: Noonday Press, (1957) ISBN 81-215-0153-9. Cited, "Nataraja", Manas, UCLA

- Classical and Folk Dances of India. Marg Publications. 1963. p. 43.

There are three types of Tandavas generally used in Kathak, namely, Krishna Tandava, Shiva Tandava and Ravana Tandava, but sometimes a fourth variety - Kalika Tandava, is also recognised .

- Marie Joy Curtiss (1970). Kathak, Classical Dance of India. University of the State of New York. p. 12.

- Vimalakānta Rôya Caudhurī (2000). The Dictionary of Hindustani Classical Music. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-208-1708-1.

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 193-194.

- Saryu Doshi 1989, pp. xvi-xviii, 44-45.

Bibliography

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande (1987). History of Indian Theatre. Abhinav. ISBN 978-81-7017-278-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reginald Massey (2004). India's Dances: Their History, Technique, and Repertoire. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-434-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saryu Doshi (1989). Dances of Manipur: The Classical Tradition. Marg Publications. ISBN 978-81-85026-09-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Description of the Class Dance (tāṇḍava), Chapter IV of the Nāṭyaśāstra