Point of sail

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

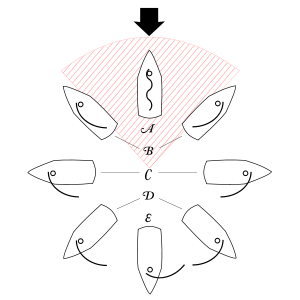

A. Into the wind; shaded: "no-go zone" where a craft may be "in irons".

B. Beating (close-hauled sails)

C. Beam reach

D. Broad reach

E. Running downwind

The principal points of sail roughly correspond to 45° segments of a circle, starting with 0° directly into the wind. For many sailing craft 45° on either side of the wind is a no-go zone, where a sail is unable to mobilize power from the wind. Sailing on a course as close to the wind as possible—approximately 45°—is termed beating, a point of sail when the sails are close-hauled. At 90° off the wind, a craft is on a beam reach. At 135° off the wind, a craft is on a broad reach. At 180° off the wind (sailing in the same direction as the wind), a craft is running downwind. The point of sail between beating and a beam reach is called a close reach.[1]

A given point of sail (beating, close reach, beam reach, broad reach, and running downwind) is defined in reference to the true wind—the wind felt by a stationary observer—and, depending on the speed of the sailing craft, determines an appropriate sail setting, as determined by the apparent wind.[1] The apparent wind—the wind felt by an observer on a moving sailing craft—determines the motive power for sailing craft.[2]

In points of sail that range from close-hauled to a broad reach, sails act substantially like a wing, with lift predominantly causing the boat to heel and to a lesser degree propelling the craft because the apparent wind is flowing along the sail. In points of sail from a broad reach to down wind, sails act substantially like a parachute, with drag predominantly propelling the craft, due to the apparent wind flowing into the sail.[1] For craft with little forward resistance, like ice boats and land yachts, this transition occurs further off the wind than for sailboats and sailing ships.[2] In the no-go zone, sails are unable to generate motive power from the wind.[1]

No-go zone

.jpg)

Sailing craft, such as sailboats and iceboats,[2] cannot sail directly into the wind, nor on a course that is too close to the direction from which the wind is blowing. The range of directions into which a sailing craft cannot sail is called the "no-go" zone.[3] In the no-go zone the craft's sails cease producing enough drive to maintain way or forward momentum; therefore, the sailing craft slows down towards a stop and steering becomes progressively less effective at controlling the direction of travel. The span of the no-go zone varies among sailing craft, depending on the design of the sailing craft, its rig, and its sails, as well as on the wind strength and, for boats, the sea state. Depending on the sailing craft and the conditions, the span of the no-go zone may be from 30 to 50 degrees either side of the wind, or equivalently a 60- to 100-degree area centered on the wind direction.[4]

In irons

A sailing craft is said to be "in irons" if it is stopped with its sails unable to generate power in the no-go zone.[4] If the craft tacks too slowly, or otherwise loses forward motion while heading into the wind, the craft will coast to a stop.[5][6] This is also known as being "taken aback," especially on a square-rigged vessel whose sails can be blown back against the masts, while tacking.[7]

Close-hauled

A sailing craft is said to be sailing close-hauled (also called beating or working to windward) when its sails are trimmed in tightly, are acting substantially like a wing, and the craft's course is as close to the wind as allows the sail(s) to generate maximum lift. This point of sail lets the sailing craft travel diagonally to the wind direction, or 'upwind'.[4] Sailing to windward close-hauled and tacking is called 'beating'. On the last tack it is possible to 'fetch' to the windward or weather mark. A fetch is sailing close hauled upwind to a mark without needing to tack.[8]

The smaller the angle between the direction of the true wind and the course of the sailing craft, the higher the craft is said to point. A craft that can point higher (when it is as close-hauled as possible) is said to be more weatherly.[9]

Reaching

When the wind is coming from the side of the sailing craft, this is called reaching.[4]

A "beam reach" is when the true wind is at a right angle to the sailing craft.

A "close reach" is a course closer to the true wind than a beam reach but below close-hauled; i.e., any angle between a beam reach and close-hauled. The sails are trimmed in, but not as tight as for a close-hauled course.

A "broad reach" is a course further away from the true wind than a beam reach, but above a run. In a broad reach, the wind is coming from behind the sailing craft at an angle. This represents a range of wind angles between beam reach and running downwind. On a sailboat (but not an iceboat) the sails are eased out away from the sailing craft, but not as much as on a run or dead run (downwind run). This is the furthest point of sail, until the sails cease acting substantially like a wing.

Running downwind

On this point of sail (also called running before the wind), the true wind is coming from directly behind the sailing craft. In this mode, the sails act in a manner substantially like a parachute.[4]

When running, the mainsail of a fore-and-aft rigged vessel may be eased out as far as it will go. Whereupon, the jib will collapse because the mainsail blocks its wind, and must either be lowered and replaced by a spinnaker, or set instead on the windward side of the sailing craft. Running with the jib to windward is known as 'gull wing', 'goose wing', 'butterflying', 'wing on wing' or 'wing and wing'. A genoa gull-wings well, especially if stabilized by a whisker pole, which is similar to but lighter than a spinnaker pole.[4] In light weather, certain square-rigged vessels may set studding sails, sails that extend outwards from the yardarms, to create a larger sail area.[10]

Sailing craft with lower resistance across the surface (multihulls, land yachts, ice boats) than most displacement monohulls have through the water can improve their velocity made good (VMG) downwind by sailing on a broad reach and jibing, as necessary to reach a destination.[11][12]

Effect on sailing craft

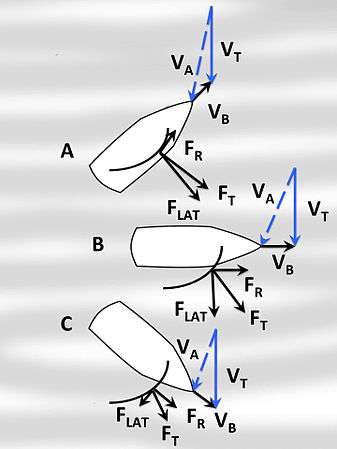

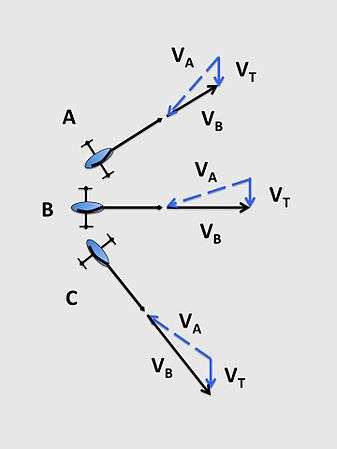

True wind (VT) combines with the sailing craft's velocity (VB) to be the apparent wind velocity (VA); the air velocity experienced by instrumentation or crew on a moving sailing craft. Apparent wind velocity provides the motive power for the sails on any given point of sail. It varies from being the true wind velocity of a stopped craft in irons in the no-go zone to being faster than the true wind speed as the sailing craft's velocity adds to the true windspeed on a reach, to diminishing towards zero, as a sailing craft sails dead downwind.[13]

- Effect of apparent wind on sailing craft at three points of sail

Sailing craft A is close-hauled. Sailing craft B is on a beam reach. Sailing craft C is on a broad reach.

Boat velocity (in black) generates an equal and opposite apparent wind component (not shown), which adds to the true wind to become apparent wind.

Apparent wind and forces on a sailboat.

Apparent wind and forces on a sailboat.

As the boat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind becomes smaller and the lateral component becomes less; boat speed is highest on the beam reach. Apparent wind on an iceboat.

Apparent wind on an iceboat.

As the iceboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind increases slightly and the boat speed is highest on the broad reach. The sail is sheeted in for all three points of sail.[2]

The speed of sailboats through the water is limited by the resistance that results from hull drag in the water. Ice boats typically have the least resistance to forward motion of any sailing craft;[2] consequently, a sailboat experiences a wider range of apparent wind angles than does an ice boat, whose speed is typically great enough to have the apparent wind coming from a few degrees to one side of its course, necessitating sailing with the sail sheeted in for most points of sail. On conventional sail boats, the sails are set to create lift for those points of sail where it's possible to align the leading edge of the sail with the apparent wind.[4]

For a sailboat, point of sail significantly affects the lateral force to which the boat is subjected. The higher the boat points into the wind, the stronger the lateral force, which results in both increased leeway and heeling. Leeway, the effect of the boat moving sideways through the water, can be counteracted by a keel or other underwater foils, including daggerboard, centerboard, skeg and rudder. Lateral force also induces heeling in a sailboat, which is resisted by the shape and configuration of the hull (or hulls, in the case of catamarans) and the weight of ballast, and can be further resisted by the weight of the crew. As the boat points off the wind, lateral force and the forces required to resist it become reduced.[14] On ice boats and sand yachts, lateral forces are countered by the lateral resistance of the blades on ice or of the wheels on sand, and of their distance apart, which generally prevents heeling.[11]

References

- Rousmaniere, John (7 January 2014). The Annapolis book of seamanship. Smith, Mark (Mark E.) (Fourth ed.). New York. pp. 47–9. ISBN 978-1-4516-5019-8. OCLC 862092350.

- Kimball, John (2009). Physics of Sailing. CRC Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-1466502666.

- Cunliffe, Tom (2016). The Complete Day Skipper: Skippering with Confidence Right From the Start (5 ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 208. ISBN 9781472924186.

- Jobson, Gary (2008). Sailing Fundamentals. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 72–75. ISBN 9781439136782.

- Cunliffe, Tom (1994). The Complete Yachtmaster. London: Adlard Coles Nautical. pp. 43, 45. ISBN 0-7136-3617-3.

- "Sailing Terms You Need To Know". asa.com. 27 November 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- "Sailing the seas of nautical language - OxfordWords blog". oxforddictionaries.com. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- Kemp, Dixon (1882). A Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing. H. Cox. pp. 97.

fetch.

- Jett, Stephen C. (2017). Ancient Ocean Crossings: Reconsidering the Case for Contacts with the Pre-Columbian Americas. University of Alabama Press. p. 528. ISBN 9780817319397.

- King, Dean (2000). A Sea of Words (3 ed.). Henry Holt. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-8050-6615-9.

- Bethwaite, Frank (2007). High Performance Sailing. Adlard Coles Nautical. ISBN 978-0-7136-6704-2.

- Batchelor, Andy; Frailey, Lisa B. (2016). Cruising Catamarans Made Easy: The Official Manual For The ASA Cruising Catamaran Course (ASA 114). American Sailing Association. p. 50. ISBN 9780982102541.

- Jobson, Gary (1990). Championship Tactics: How Anyone Can Sail Faster, Smarter, and Win Races. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 323. ISBN 0-312-04278-7.

- Marchaj, C. A. (2002), Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximize Sail Power (2 ed.), International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press, p. 416, ISBN 978-0071413107

Bibliography

- Rousmaniere, John, The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Simon & Schuster, 1999

- Chapman Book of Piloting (various contributors), Hearst Corporation, 1999

- Herreshoff, Halsey (consulting editor), The Sailor’s Handbook, Little Brown and Company, 1983

- Seidman, David, The Complete Sailor, International Marine, 1995

- Jobson, Gary, Sailing Fundamentals, Simon & Schuster, 1987