Syed Shamsul Huda

Syed Shamsul Huda KCIE (1862–1922) was a Muslim political leader and scholar in British India. He was born in the village of Gokarna, now known as Gokarna Nawab Bari Complex,[1] in Nasirnagar Upazila, Brahmanbaria District, which was earlier integrated into the greater Comilla District that was a part of Hill Tipperah.[2], before Partition

Syed Shamsul Huda | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The first Indian Muslim President of the reformed Legislative council of undivided Bengal in 1921 | |

| Born | 1862 |

| Died | 14 October 1922 |

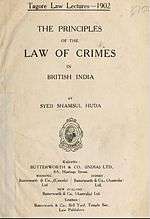

Notable work | The Principles of the Crimes of Law in British India published by Butterworth & Co.,(India) Ltd.-1902. |

His father was Syed Riazat Ullah, the editor of The Doorbeen, a Persian-language weekly journal.

Education

Syed Shamsul Huda's primary education—in Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Bengali, and the science of Islam—was completed at home under his father. He was then admitted to Hooghly High Madrasah at Calcutta to complete a traditional education. After that, he obtained a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree from Presidency College in 1884, and a Bachelor of Law (BL) degree from Calcutta University in 1886. He received a Master of Arts (MA) degree, in Persian, privately from Presidency College in 1889.

Huda was schooled in many fields of knowledge, and became one of the most eloquent, articulate, and educated Muslims of his generation. He had an important role as Muslim scholar, leader, and politician in British India at the beginning of the twentieth century.[3]

Career

Huda joined the Calcutta Madrasah in 1885 as a lecturer in Arabic and Persian. Two years later, he left the madrasah to practice law before the Calcutta High Court[3] and gradually became involved in politics.

The Indian National Congress was established in 1885 by Calcutta's Hindu leaders. This political body was proposed to symbolize all the people of India, together with Hindu and Muslim population. Prominent Indian Muslim leaders including Sir Syed Ahmad Khan CSI, Nawab Abdul Latif and Syed Ameer Ali, firstly gave their full support to this political body. But later on, the Hindu Congress leaders began practicing partition. Muslim leaders called Second Annual Meeting of the Calcutta Union about the political attitude and future plan of the Congress in 1895. Syed Shamsul Huda attended and addressed to stop the issue on the title of "Indian Politics and the Muhammadans" and in this way he became the top of the political dialogue. In his speech, he highlighted the political rule of the Indian Muslim and suggested ways they could make the Congress more united and effective political body.[3]

Huda's first role as a political leader was in opposing the budget for 1905, in which spending for colleges, hospitals, and other institutions was predominantly for those in districts near Calcutta. He proposed a policy of increased spending for such institutions for East Bengal as well, which was eventually established, and proved advantageous to the Muslims of Eastern Bengal, while being opposed by elite Hindus. As a man of education, political consciousness, and perception, Huda articulated the new situation. He wrote:

I claim that after the creation of the new Province, East Bengal has received a great deal more of personal attention. Before the Partition the largest amount of money used to be spent in districts near Calcutta. The best of Colleges, Hospitals, and other institutions were founded in or near about the Capital of India. Bengal alone now reaps the benefit of those institutions towards which both the Provinces had contributed. We have inherited a heritage of the accumulated neglect of years and cannot be blamed if [we] require large sums to put our house in order.[4]

He also mentioned on another occasion:

They [Hindus] have benefited for very many years out of the revenues of Eastern Bengal and have paid very little for its progress and advancement ... I will only say that if Eastern Bengal now for some years costs money, and if that money is to come from any province outside East Bengal, it should come from Western Bengal and the members from that province should not as any rate grumble at it.[4]

Huda was made a fellow of Calcutta University in 1902. He was invited to give the Tagore Law Lecture, which was published by Butterworth & Co,(India) Ltd, under the title The Principles of the Law of Crimes in British India.[5] He developed a theory of the basic law of offenses, following along the lines of the work of British jurists such as Jeremy Bentham, William Austin, and William Blackstone. He presided over the Provincial Muhammadan Educational Conference at Rajshahi in 1904. He was a member of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of East Bengal and Assam in 1908. He was a President of the All India Muslim League in 1910. He became a member of the Imperial Legislative Council between 1911 and 1915, as a Leader for the Muslims of East Bengal.

He is one of the leaders of public opinion in his Province, and is On the forefront of all movements concerning the Mohammadan community.[4]

.jpg)

Between 1912 and 1919, Huda was a member of the governor of Bengal's executive council.[6] He was awarded the title of nawab in 1913. He was made KCIE in 1916.[7] He was designated a judge on the Calcutta High Court in 1917, becoming the second Muslim from Bengal to occupy a seat, after Justice Syed Ameer Ali.

Thomas Gibson-Carmichael stated:

In all my endeavours to promote the welfare and to meet the legitimate desires of your community (Musalmans) I have been ably advised by my colleague the Hon'able Nawab Sir Syed Shamsul Huda; and I am glad to take this opportunity to testify to the fact that in my judgement the Mohamedan community in Bengal could have had no more sympathetic or better advocate than he has been.[8]

Huda became the first Indian Muslim president of the reformed legislative council of undivided Bengal in 1921.

His term of office as the first President of the Bengal Legislative Council under the reformed constitution was the crowning distinction of a career in which he had already earned honours enough to satisfy the ambition of most men. In accepting that office he rendered the greatest service within his power to Bengal and to the Reforms - a service which will always be held in honourable remembrance. Until failing health compelled his retirement he gave his energies and his exceptional abilities ungrudgingly for the benefit of his countrymen, who will treasure his memory with gratitude.[8]

Surendranath Banerjee stated:

The late Nawab Shahib was not a sectarian in any sense of the word. He never made any distinction between Hindus and Muhammadans. He was devoid of all class hatred. He was never unreasonable in his demands for the rights and claims of his co-religionists. In fact he was a gentleman in the highest sense of the word.[8]

Throughout his whole life Sir Shamsul Huda worked for the cause of Islam and he had no other aim in this world. Even if this statement is somewhat exaggerated, there is no doubt that the progress and development of the Muslims of Bengal was very close to his heart. He worked round the clock to improve the existential condition of his fellow Muslims during his long and distinguished career as a jurist, leader and politician.[9]

Contributions to education

Huda was a patron of the Muslim students of Bengal during a difficult period. He created student accommodations by founding the Carmichael Hostel for rural university-going Muslim students in Calcutta. For the establishment of the Elliot Madrasah Hostel in 1898, he obtained two-thirds of the funds from the government, with the remainder, a sum of Rs. 5,400, being contributed by the Nawab Abdul Latif Memorial Committee. Huda created the post of "assistant director for Muslim education" for each division.

He sanctioned the large sum of Rs. 900,000 from the Bengal government to purchase land to establish a government college for Muslims in Calcutta. Because of the First World War, the opening ceremony was postponed until 1926, when Abul Kasem Fazl-ul-Haq became education minister of the united province.[10]

In 1915, on his ancestral property, he founded Gokarna Syed Waliuallah High School, which was named after his same-aged uncle.[11] It was the first government-aided school in Nasirnagar Upazila for Hindu and Muslim students.

The University of Dhaka was established in 1921 by Lawrence Ronaldshay, the Governor of Bengal, who served as chancellor and who designated Huda as a life member of the university. On Huda's recommendation, Lord Ronaldshay appointed Sir A. F. Rahman as a provost.[8]

Huda financed the journals Sudhakar (1889), The Urdu Guide Press, and The Muhammadan Observer (1880).[10] Religious constraints prevented women from gaining an education in Bengal. He supported and encouraged the Bengal Women's Education Project, founded by Begum Rokeya for women's education and development.[12]

Death

Huda lived at 211 Lawyer Circular Road, Calcutta. He died on 14 October 1922, at the age of 61, and was buried in Tiljola Municipal graveyard. The Calcutta Weekly Notes wrote of his death:

Starting life as a vakil of the Calcutta High Court, he took for years a leading part in the affairs of his own community, the city and the University and served with distinction in the Legislative Councils of the Province and the Government of India. As a vakil he long enjoyed a leading practice. For tact, breadth of mind, fair-mindedness and a shrewd yet well balanced judgement which seldom failed to take in the essentials of the most complicated situation at a glance, he had hardly an equal and few indeed on this side of India to surpass him. His genial temperament won him many friends in nearly every walk of life. He filled several high offices but his services to the public will be chiefly remembered in connection with his appointment as a Member of the Executive Council during Lord Carmichael’s Governorship of Bengal. In this capacity, his countymen found in him a staunch and powerful champion of their just claims and [he] was trusted by Hindus and Mahomedans alike, which itself was a significant tribute to his independence of outlook, catholicity and large heartedness... Sir Shamsul Huda has passed away at the time when his countrymen have stood in the greatest need of that happy combination of qualities which make leadership and which he possessed in a pre-eminent degree.[9]

References

- "Nasirnagar Upazilla". Bangladesh National Portal.

- Princely States of India

- Khan, Muhammad Mojlum (2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal. Kube Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-84774-059-5.

- Khan, Muhammad Mojlum (2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal. Kube Publishing Ltd. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-84774-059-5.

- "Books Received". Harvard Law Review. 33 (8): 1084–1086. June 1920. JSTOR 1327638.; "Books Received". Yale Law Journal. 30 (1): 107–108. November 1920. JSTOR 786705.

- Elite Conflict in a Plural Society: Twentieth-century Bengal, J. H. Broomfield, University of California press, page 51; Who's who in India, Poona 1923; and Who's Who, 1923 (London, 1923).

- Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Nawab". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Khan, Muhammad Mojlum (2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal. Kube Publishing Ltd. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-84774-059-5.

- Khan, Muhammad Mojlum (2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal. Kube Publishing Ltd. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-84774-059-5.

- Indian Muslim and Partition of India, S.M. Akram, Atlantic Publishers and Distributors, pages 298–299.

- Gupta, Amita (2007). Going to School in South Asia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-313-33553-2.

- Amin, Sonia Nishat (1996). The World of Muslim Women in Colonial Bengal, 1876-1939. Brill. p. 158. ISBN 978-90-04-10642-0.