Svetovid

Svetovid, Svantovit[1][2][3] or Sventovit[4] is a Slavic deity of war, fertility and abundance.

| Svetovid | |

|---|---|

God of war, fertility and abundance, supreme deity | |

Modern statue of Svetovid at Cape Arkona, Rügen island, (today Germany) | |

| Abode | temple at Arkona, Rügen island |

| Symbol | four heads or faces, white stallion, horn of plenty, sword |

| Mount | white stallion |

It was primarily venerated on the island of Rügen into the 12th century. He is often considered a local Rugian variant of the pan-Slavic god Perun.

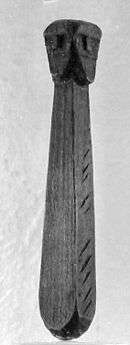

Sometimes referred to as Beli (or Byali) Vid (Beli = white, bright, shining), Svetovid is associated with war and divination and depicted as a four-headed god with two heads looking forward and two back. A statue portraying the god shows him with four heads, each one looking in a separate direction, a symbolic representation of the four directions of the compass, and also perhaps the four seasons of the year. Each face had a specific color. The northern face of this totem was white (hence White Ruthenia / Belarus and the White Sea), the western, red (hence Red Ruthenia), the southern, black (hence the Black Sea) and the eastern, green (hence Zeleny klyn).[5]

Etymology

.jpg)

The forms Sventevith and Zvantewith show that the name derives from the word svętъ, meaning "sacred". The second stem is sometimes reconstructed as vit = "lord, ruler, winner".

The name recorded in chronicles of contemporary Christian monks is Svantevit, which, if we assume it was properly transcribed, could be an adjective meaning approx. "Dawning One" (svantev, svitanje = "dawning, raising of the Sun in the morning" + it, adjective suffix), implying either a connection with the "Morning Star" or with the Sun itself.

Alternative names

Beyond the names above referenced, Svetovid can also be known as Svitovyd (Ukrainian), Svyatovit (alternative name in Ukrainian), Svyentovit (alternative name in Ukrainian), Svetovid (Serbian, Croatian, Slovenian, Macedonian and Bosnian, and alternative name in Bulgarian), Suvid (alternative name in Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian), Svantevit (Wendish, alternative name in Ukrainian and possibly the original proto-Slavic name), Svantevid (alternative name in Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian), Svantovit (Czech and Slovak), Svantovít (Czech), Svantovid (alternative name in Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian), Swantovít, Sventovit, Zvantevith (Latin and alternative name in Serbian and Croatian), Świętowit (Polish), Sutvid, Svevid, and Vid.

- The modern reconstruction of Pomeranian Wolin Idol in archeological museum, sometimes said to represent Svetovid

Worship

One of the inhabitants of the Rügen island in the Baltic Sea were the Slavic tribe of the Rujani, whose name was cognate of the island's.

According to various chronicles (i.e. Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus and Chronica Slavorum by Helmold), the temple at Jaromarsburg contained a giant wooden statue of Svantevit depicting him with four heads (or one head with four faces) and a horn of abundance. Each year the horn was filled with fresh mead.

The temple was also the seat of an oracle in which the chief priest predicted the future of his tribe by observing the behaviour of a white horse identified with Svantevit and casting dice (horse oracles have a long history in this region, being already attested in the writings of Tacitus). The temple also contained the treasury of the tribe and was defended by a group of 300 mounted warriors which formed the core of the tribal armed forces.

Origins

David Leeming identifies the four heads as Rujevit, representing autumn and east, Porevit, representing summer and south, Iarovit, representing spring and west, and Bialobog, representing winter and north.[6]

Some interpretations claim that Svetovit was another name for Radegast, while another states that he was a fake god, a Wendish construction based on the name St. Vitus. However, the common practice of the Christian Church was to replace existing pagan deities and places of worship with analogous persons and rituals of Christian content, so it seems more likely that Saint Vitus was created to replace the original Svanto-Vit. According to a common interpretation, Svantevit was a Rugian counterpart of the pan-Slavic Perun.

In Croatia, on the island of Brač, the highest peak is called Vid's Mountain. In the Dinaric Alps there is a peak called "Suvid" and a Church of St. Vid. Among the Serbs, the cult of Svetovid is partially preserved through the Feast of St. Vitus, "Vidovdan", one of the most important annual events in Serbian Orthodox Christian tradition.[7]

In popular culture

The science fiction story "Delenda Est" by Poul Anderson depicts an alternate history world where Carthage defeated Rome, Christianity never arose and in the 20th century, Svantevit is still a main deity of a major European power called Littorn (that is, Lithuania). A devotee of this god, in the story, is called Boleslav Arkonsky – a name evidently derived from the above-mentioned temple at Arkona.

An installation on the 2019 LUMA Projection Arts Festival was based on Svetovid.[8]

See also

- The Slav Epic (Painting: "The Celebration of Svantovit")

References

- A History of Pagan Europe by Prudence Jones and Nigel Pennick. Retrieved 10 Jan 2014.

- The Oxford Companion to World Mythology by David Leeming. Retrieved 10 Jan 2014.

- New Larousse encyclopedia of mythology by Félix Guirand and Robert Graves, Hamlyn, 1968. Retrieved 10 Jan 2014.

- American, African, and Old European Mythologies edited by Yves Bonnefoy. Retrieved 10 Jan 2014.

- Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedic dictionary, Kyiv, 1987.

- Leeming 2005, p. 359-360.

- Đorđević, Dimitrije (Spring 1990). "The role of St. Vitus Day in modern Serbian history" (PDF). Serbian Studies. North American Society for Serbian Studies. 5 (3): 33–40.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- https://lumafestival.com/feature/sviatovid/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Svetovid. |