Mokosh

Mokosh (Old East Slavic: Мóкошь) is a Slavic goddess mentioned in the Primary Chronicle, protector of women's work and women's destiny.[1] She watches over spinning and weaving, shearing of sheep, and protects women in childbirth. Mokosh is the Great Mother.[2]

| Mokosh | |

|---|---|

Life-giving and life-taking, fertility and moisture | |

Modern wooden statue in the Czech Republic | |

| Symbol | Sun |

| Personal information | |

| Consort | Perun and Veles (assumption) |

| Children | Jarilo and Morana |

| Roman equivalent | Terra, Minerva or Juno |

| Christian equivalent | Paraskevi of Iconium, Virgin Mary |

Mokoš was the only female deity whose idol was erected by Vladimir the Great in his Kiev sanctuary along with statues of other major gods (Perun, Hors, Dažbog, Stribog, and Simargl).

Etymology and origin

Mokosh probably means moisture. According to Max Vasmer, her name is derived from the same root as Slavic words mokry, 'wet', and moknut(i), 'get wet'. Or to dive deeply into something. She may have originated in the northern Finno-Ugric tribes of the Vogul, who worship the divinity Moksha.[3] Her name might also have originated in the proto-indo european word molqos which means "wet".

Myth

Mokosh was one of the most popular Slavic deities and the great earth Mother Goddess of East Slavs and Eastern Polans. She is a wanderer and a spinner. Her consorts are probably both the god of thunder Perun and his opponent Veles. In saying, the former Katičić follows Ivanov and Toporov (1983) without further corroborating their claim.[4] Katičić also points to the possibility that as goddess Vela she is the consort of Veles, and might even be interpreted as another form of the polymorph god Veles himself.[4]:167–198 Mokosh is also the mother of the twin siblings Jarilo and Morana.

Archeological evidence of Mokosh dates back to the 7th century BC.[5] As late as the 19th century, she was worshipped as a force of fertility and the ruler of death. Worshipers prayed to Mokosh-stones or breast-shaped boulders that held power over the land and its people.[6]

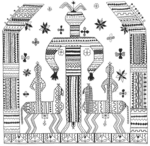

In Eastern Europe, Mokosh is still popular as a powerful life-giving force and protector of women. Villages are named after her. She shows up in embroidery, represented as a woman with uplifted hands and flanked by two plow horses.[7] Sometimes she is shown with male sexual organs, as the deity in charge of male potency.[8]

A key myth in Slavic mythology, is the divine battle between the thunder god Perun and his opponent the god Veles. Some authors and the original researchers Ivanov and Toporov believe, the abduction of Mokosh causes the struggle.[lower-alpha 1][9]

According to Boris Rybakov, in his 1987 work Paganism of Ancient Rus,[10] Mokosh is represented on one of the sides of the Zbruch Idol.

Christianization

.jpg)

During Christianization of Kievan Rus', there were warnings issued against worshipping Mokosh. She was replaced by the cult of the Virgin Mary and St. Paraskevia.[11]

Traces of Mokosh in place names

Traces of Mokosh are today well preserved in the various toponyms of Slavic countries. In Slovenia, her name has been preserved in a village called Makoše in the vicinity of Ribnica, historically known as Makoša or Makoš, and also in the River Mokoš in the Prekmurje region. In Croatia, near the Rieka lies the village of Mokošica, and near Dubrovnik the village Makoše, and also the suburb areas of Nova and Stara Mokošica. A village near Zagreb is also called Mokos. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, near the village Ravno is located a hill called Mukušina. South of Mostar lies the hill Mukoša.[12]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mokosh. |

- Kikimora

- Moksha

- Mokshas tribe

- Moksha language

References

- Ivanits, Linda J. (February 15, 1989). "Russian Folk Belief". M.E. Sharpe – via Google Books.

- Katičić, Radoslav (2003). Die Hauswirtin am Tor: Auf den Spuren der großen Göttin in Fragmenten slawischer und baltischer sakraler Dichtung. Frankfurt am Main: PETER LANG. p. 40. ISBN 3-631-50896-4. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Hubbs, Joanna (Sep 22, 1993). Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture. Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0253115787 – via Google Books.

- Katičić, Radoslav (2010). Gazdarica na vratima: Tragovima svetih pjesama naše pretkršćanske starine. Zagreb: IBIS GRAFIKA. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-953-6927-59-3.

- Harald Haarmann (2008). "". Introducing the Mythological Crescent: Ancient Beliefs and Imagery p. 98

- Patricia Monaghan (2010). "". Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines p. 516

- Ivanits, Linda J. (February 15, 1989). "Russian Folk Belief". M.E. Sharpe – via Google Books.

- Hubbs, Joanna (September 22, 1993). "Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture". Indiana University Press – via Google Books.

- Евдокимова, Светлана; Evdokimova, Professor of Slavic Studies and Comparative Literature Chair Department of Slavic Studies Svetlana (July 26, 1999). "Pushkin's Historical Imagination". Yale University Press – via Google Books.

- Boris Rybakov (1987). "Святилища, идолы и игрища". Язычество Древней Руси (Paganism of Ancient Rus) (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Vyacheslav Ivanov, Vladimir Toporov. Mokoš./ В. В. Иванов, В. Н. Топоров - «Мокошь». Мифы народов мира, т. II. М.:Российская энциклопедия, 1994.

- Češarek, Domen (2016). "Mala gora pri Ribnici – mitološko izročilo v prostoru (Mala Gora (Little Mountain) by Ribnica – Cosmic myth in mythical landscape)" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. 19: 135.

Notes

- Although Ivanov and Toporov nowhere quote original sources indicating that fact. Compare: Katičić (2010):210