Susak

Susak (Italian: Sansego; German and French: Sansig) is a small island on the northern Adriatic coast of Croatia. The name Sansego comes from the Greek word Sansegus meaning oregano which grows in abundance on the island. A small percentage of natives still reside on the island which has increasingly become a popular tourist destination—especially during the peak summer months. Many of the people from Susak currently live in the United States.

Susak Village | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Adriatic Sea |

| Coordinates | 44°31′N 14°18′E |

| Area | 3.8 km2 (1.5 sq mi) |

| Length | 3.6 km (2.24 mi)[1] |

| Width | 2.3 km (1.43 mi)[1] |

| Highest elevation | 98 m (322 ft) |

| Highest point | Garba |

| Administration | |

| County | Primorje-Gorski Kotar |

| Largest settlement | Susak |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 151 (2011)[2] |

| Pop. density | 39.74/km2 (102.93/sq mi) |

Geography

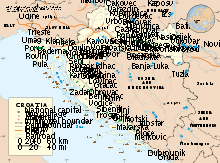

Located in the Kvarner Bay and southeast of the Istrian peninsula, the Croatian island of Susak is 7.4 kilometers (4.6 mi; 4.0 nmi) southwest from the island of Lošinj,[3] 10 kilometers (6.2 mi; 5.4 nmi) south of the island of Unije, and 120 kilometers (75 mi; 65 nmi) east of the Italian coast. Susak is about 3 km (1.9 mi) long and 1.5 km (0.9 mi) wide, and covers an area of approximately 3.8 square kilometers (1.5 sq mi).[4] Susak's highest elevation point, Garba is 98 metres (322 feet) above sea level.[1][3]

The island is geologically different from other Adriatic islands in that it is mostly formed of fine sand laid on a limestone rock base. The way sand appeared on the island has not been fully settled: while some scientists speculate that Susak formed as a result of sediment deposits from the river Po during the last ice age,[5] which rose above the surface through tectonic activity, others believe Susak's sand is of eolic origin.[6] Due to the porous soil, there are no permanent water streams or other bodies of water on the island.[6]

History

Susak's history is a rich and complex story. Unfortunately, little of it prior to the 20th century is known. This is a result of mainly three factors. First, few of Susak's inhabitants prior to the 20th century had formal education. Before the massive exodus off the island after World War II, it was rare to find a resident who had finished the equivalent of grade school. Next, most of the island's history was not recorded – it was passed down orally. Finally, and probably most prevalent, the island's history was consistently manipulated, suppressed, and influenced by those who were its current rulers. For example, even the island's name changed at least three times (Sansagus, Sansego, and Susak) depending on which government controlled it. For these reasons, it is difficult to precisely piece together the island's history.

Mythical origins

"In Antiquity, when the archipelago was home to a Greek colony, the islands were called the Absyrtides. This is because, according to an episode in the legend of the Argonauts, Jason and Medea were said to have taken refuge here on the island of Minerva to escape pursuit by Absyrtus, the sorceress's brother, after they had stolen the golden fleece. Medea's brother found them, however, and fell into a trap she had laid: he was chopped into pieces and thrown into the sea where his body parts formed the many islets surrounding Cres and Lošinj. The Kolchians, who had come with them, remained here and founded the city of Absoris."[7][8]

Antiquity through Napoleon

The name of Susak is believed to be derived from sampsychon (Greek for marjoram), which was later transformed into sansegus and sansacus in Romance languages, and finally adopted by Slavs as Susak.[9]

There is speculation that Susak has been settled for at least two thousand years by Illyrians, Greek sailors, and Romans (as a summer resort for wealthier Roman citizens[3]). While there is little or no surviving evidence from Susak supporting this claim, there are ancient remains - including buildings, mosaics, coins, and burial sarcophagi - on other islands surrounding Susak. The latest Susak would have been settled is during the early Middle Ages.[10] Assuming Susak was settled then, probably Slavs would have ruled the island under the Byzantine Empire during that time period (circa 500 CE through circa 1000 CE).

Giovanni the Deacon wrote the earliest surviving text referencing Susak in the early 11th century. He wrote about Saracens in 844 destroying a fleet of Venetian ships. The surviving ships were said to have fled to Sansego.

Susak was likely governed by the Croatian Kingdom during the 10th and 11th centuries. In or around 1071, the Croatian King Krešimir gave Susak to Benedictine monks to build an abbey on the island. The Benedictine monks governed Susak until sometime between the 12th century and 1267. 1267 is the year Istria became a territory of the Republic of Venice and it is likely that Susak was also ceded to the Venetians at or around the same time. The monastery was operational from the 11th century until 1770 when the Church of Saint Nicholas was built to replace it.

Between the 13th and 18th centuries, Susak is mentioned in various documents, charts and official papers of Venetian doges. Around 1280, the oldest surviving nautical chart mentioning Susak, the Carta Pisana is published.[3] Between the 16th and 18th centuries, cartographers detail a settlement on Susak. In 1593, Christiaan Sgrooten[11] was the first to chart a settlement on the island. In the late 17th century, the cartographer Cornellius mentioned a tower on Susak: Villa e torre di Sansego. In 1771, cartographer Alberto Fortis cited a settlement on Susak with a church, harbor, and several coves and capes.

After the Benedictine monks, the Republic of Venice was next to rule Susak. Venetian rule lasted until April 17, 1797 when Napoleon Bonaparte signed the Treaty of Leoben ceding the land between Istria and Dalmatia (including Susak) to Austria. The proposed secession of this land to Austria was ratified on October 17, 1797 by the Treaty of Campo Formio.

Napoleon through modern times

Although Susak was now part of the Austrian Empire, it was still under Napoleon's jurisdiction. This area between Istria and Dalmatia during this time (1797 through 1815) was known as the Illyrian provinces of Napoleon’s Empire or Napoleon’s Illyria for short.

After Napoleon's exile, the Austrian Empire annexed Susak and much of the region per a Viennese congressional resolution. The Austrian Empire and subsequently the Austro-Hungarian Empire ruled over the island for the next 100 years from roughly 1815 through the end of World War I, in 1918. Under Austro-Hungarian rule, Susak became part of the Austrian Littoral or Küstenland.

After the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I, the 1919 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye gave Susak and several other territories to the relatively new nation of Italy. The Italian government under the fascist government of Benito Mussolini began the Italianization of these new Italian territories. On Susak, for example, the Italian government changed the spellings and pronunciations of several of the island's surnames. Tarabokija became Tarabocchia; Picinić became Picini. {immigrants from Susak would give Italian as their ethinicity and non Croatian, they themselves would spell Tarabocchia instead of Tarabokija since the Austro-Hungarian government had spent many efforts to reduce the Italian population.

Italian sovereignty of Susak ended in September 1943 when the Allies invaded Italy. The Nazis established the Operation Zone of the Adriatic Littoral and took control of the area including Susak. The Nazis remained on the island until the end of World War II in 1945.

In 1947, the Paris Peace Treaty formally ended World War II. Susak became part of the Socialist Yugoslavia under Marshal Tito. Yugoslavia consisted of 6 republics, 1 autonomous district, and 1 autonomous province, Susak becoming a part of the Socialist Republic of Croatia. Around the middle of the 20th century, Susak experienced a mass exodus.

On June 25, 1991, Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia and Susak remained a part of newly formed Republic of Croatia.

Population

Susak's inhabitants reside in a single settlement of the same name. The settlement has two parts: atop a small hill, Gornje Selo is the older part of the village where the island's church is located; and Donje Selo is the lower part of the village adjacent to the seashore and small harbor.

Between 1948 and the early 1960s, the island's population plummeted because of the Istrian Exodus. As of 2011, Susak had only 151 residents with approximately 2,500 emigrants or descendants of emigrants living in New Jersey, United States.[12] While the greatest concentration of emigrants and descendants currently live in the New York City metropolitan area (particularly in northern New Jersey), most went to Hoboken, New Jersey, people from Susak can be found living throughout the United States.

There are only about a dozen surnames from Susak.[5] The engravings on the island's white tombstones boast these names (or some form of them): Busanić, Hrončić, Lister, Matešić, Mirković, Morin, Picinić, Sutora, Skrivanić, and Tarabokija.

Before World War II, most if not all of the inhabitants labored as vintners, farmers, fisherman, or some combination of all three occupations. Today, the island's emigrants and descendants hold a wide variety of professions from longshoremen to conductors and from engineers to lawyers.

| Year | 1680 | 1785 | 1857 | 1910 | 1921 | 1931 | 1936 | 1948 | 1953 | 1964 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 91[13] | 357[13] | 1089 | 1412 | 1564 | 1541 | 1656[13] | 1629 | 1438[14] | 634[14] | 188 | 188[15] | 151 |

Expulsion of Ethnic Italians and Exile in America

Italians in Julian region were under extreme pressure to leave after the war. The climate for to Italians to stay, especially after the mass killings of Italians in nearby Istria, was poor. The Croat and Slovenian nationalists in socialist government sought to impose collective punishment on the Italians after annexation to Slavic state (Republic of Croatia in Yugoslav federation). Habitants of Susak-Sansego spoken in specific sansegotic's language, koine of romanic and slavic language and they don't liked proces of croatization in Croatia. Faced with poverty, famine, lack of employment opportunities, along with the desire for a better life, the island experienced a mass exodus between 1948 through the mid-1960s directly due to the political climate and nationalist policies. After World War II, Yugoslavia's new government, required that all able men work for a period of time without payment. Many of the Sansegots (people from Susak) by the mid-1960s, more than 80 percent of population had left the island.

Susak's inhabitants immigrated to the United States for two main reasons. First, they believed that the United States would be able to offer them better opportunities for wealth, employment, education, and standard of living. Second, majority of the people who emigrated from Susak prior to World War II had moved to the United States, primarily to Hoboken, New Jersey.

Economy

For much of the island's history, Susak's inhabitants supported themselves by making wine, farming, and fishing. The islanders produced a significant quantity of wine and grappa between 1936 and 1969 when a cooperative wine cellar aided in the production and manufacturing of the beverages. At one time, there was also a fish cannery on the island.

By the mid-1960s, Susak had become almost completely depopulated with its main town in virtual ruin.

Today, tourism is Susak's main industry although some wine is still produced - particularly a red wine called pleskunac and a dry rosé called trojiśćina. Between June and September, several hundred tourists are visiting the island each day, over night or on day-long excursions.[12] In the peak of the tourist season, in July and August, the island's population swells up to 1,500.[12] A boost to Susak's tourism is the Susak Expo [16] – an international annual art event attracting leading, contemporary artists, which has, in recent years, gained a reputation similar to the Venice Biennial.

Customs and traditions

Due to its significant distance from mainland Croatia and the many cultures which have through the years governed it, the people from Susak have many unique traditions. Some traditions are exclusively the island's own (such as the island's language and the fanciful clothing). Other traditions, such as cuisine, are a blend of the diverse customs from southern and central Europe.

The people from Susak speak a distinct dialect which is heard only on the island and among the older generation of the island's emigrants. Additionally, most of the island's population over the age of 60, to varying degrees, speaks Italian.

The islanders have a custom of referring to each other by nicknames, and the outsiders who visit Susak are often given a nickname too.[5]

Costume and clothing

Susak is perhaps best known for the ornate and elaborate costumes worn by younger women primarily for special occasions such as a wedding or feast day. The costume is made up of a short, brightly, almost neon, colored skirt with multiple ruffled petticoats underneath which gives the wearer the appearance that she is dressed in a ballet tutu. A similar-colored vest is generally worn over a long-sleeved, white chemise. The outfit is accentuated by pink or orange woolen stockings, leather shoes, and a headpiece which matches the colors of the skirt. When wearing this traditional outfit, women generally place one or both hands their hips to emphasize the dress's uniqueness.

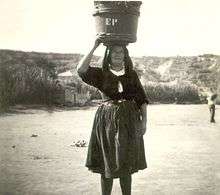

Older and working women generally wear darker, longer skirts without ruffled petticoats. They wear white or dark, long-sleeved shirts, a short veil to cover their hair, and dark, woolen stockings.

Male costumes from Susak are less ornate than their female counterparts. Men traditionally wear dark trousers and a dark vest over a long-sleeved, white, collared shirt. The outfit is completed by a soft, dark cap and may be accentuated with a colorful belt or ribbons on the vest.

During a period of mourning—generally following the death of close family member such as a spouse, parent, sibling, or child—people from Susak wear all black for a period of time.

Food

Susak's cuisine combines a unique blend of Italian, Croatian, Austrian, and Mediterranean cooking. Seafood—especially fish such as sardines, mackerel, and grouper—is popular fare due to its relative abundance. Lamb and pork cooked on an open fire are also popular but are generally reserved for special occasions.

For dessert, the people of Susak enjoy Palacinke filled with jam or fruit, strudel (a throw-back from when the island was under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), or losi, a fried pastry made with flour and sprinkled with powered sugar.

References

- "Susak". Croatian Encyclopedia (in Croatian). Zagreb: Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Ostroški, Ljiljana, ed. (December 2015). Statistički ljetopis Republike Hrvatske 2015 [Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Croatia 2015] (PDF). Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Croatia (in Croatian and English). 47. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. p. 47. ISSN 1333-3305. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- Ostojić 2002, p. 388.

- Duplančić Leder, Tea; Ujević, Tin; Čala, Mendi (June 2004). "Coastline lengths and areas of islands in the Croatian part of the Adriatic Sea determined from the topographic maps at the scale of 1 : 25 000" (PDF). Geoadria. Zadar. 9 (1): 5–32. doi:10.15291/geoadria.127. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- "Nevjerojatna i tužna priča o jednom od naših najizoliranijih otoka koji je u završnoj fazi demografske katastrofe". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). HINA. 22 October 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Sokolić 1994, p. 504.

- Knopf, Alfred (2005). Croatia and the Dalmatian Coast. Knopf Guides. ISBN 0-375-71112-0.

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, Stephen Trzaskoma (2004). Anthology of classical myth: primary sources in translation. Stephen Trzaskoma, R. Scott Smith, Stephen Brunet, Thomas G. Palaima, Hackett Publishing. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-87220-721-9.

- Sokolić 1994, p. 509.

- Springer, Zvonko. "Zvonko's Travels: Island of Susak".

- "Chrisiaan Sgrooten".

- Ostojić 2002, p. 389.

- Turčić 1998, cited in Ostojić 2002, p. 388

- Turčić 1998, cited in Ostojić 2002, p. 389

- Turčić 1998, cited in Ostojić 2002, pp. 388–389

- "Susak Expo".

Sources

- Ostojić, Borislav (May 2002). "Opskrbljivanje stanovništva otoka Suska pitkom vodom" [Potable water public supply on the island of Susak] (PDF). Pomorski zbornik (in Croatian). 40 (1): 387–408. Retrieved 12 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sokolić, Julijano (July 1994). "Otok Susak – mogućnosti revitalizacije" [The island of Susak - prospects of revitalization] (PDF). Društvena istraživanja (in Croatian). 3 (4–5 (12–13)): 503–515. Retrieved 14 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turčić, Don Antun (1998). Susak - otok pijeska, trstike i vinograda [Susak - the Island of Sand, Reed and Vineyards] (in Croatian). Susak: Parish office. ISBN 953-96752-1-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Susak - Environmental Reconstruction of a Loess Island in the Adriatic. Budapest: Geographical Research Institute, Hungarian Academy of Sciences. 2003.

- Bousfield, Jonathan (2003). The Rough Guide to Croatia. Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-084-8.

- Jo, Melvin (2006). Susak Conversations. Susak Press. ISBN 978-1-905659-02-9.

- Filipović, Rudolf (1997). Eliasson, Stig; Jahr, Ernst (eds.). The Struggle to Maintain Croatian Dialects in the U.S. Trends in Linguistics; Studies and Monographs 100; Language and Its Ecology. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-014688-6.

- Foster, Jane (2004). Footprint Croatia. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 1-903471-79-6.

- Mirković, Mijo, ed. (1957). Otok Susak: zemlja, voda, ljudi, gospodarstvo, društveni razvitak, govor, nošnja, građevine, pjesma i zdravlje. Djela Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti (in Croatian). 49. Zagreb: Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts.

- Oliver, Jeanne (2005). Croatia. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-487-8.

- Strcić, Petar; et al. (1996). Croatian Adriatic Islands. Zagreb: Laurana & Trsat.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Island of Susak. |

- Island of Susak - touristic information - houses

- Island of Susak - touristic information

- Official Susak Expo site

- Susak Klapa Online

- Island of Susak

- Sansego.net

- Slide show of a wedding held on the island in 1957 - notice the traditional and elaborate outfits (particularly worn by women)

- Otok Susak (site is in Croatian)

- Istria on the Internet

- Folk Costumes from Istria

- Susak Press