Suoyang City

Suoyang City (Chinese: 锁阳城; pinyin: Suǒyáng Chéng), also called Kuyu (苦峪), is a ruined Silk Road city in Guazhou County of Gansu Province in northwestern China. First established as Ming'an County in 111 BC by Emperor Wu of Han, the city was relocated and rebuilt at the current site in 295 AD by Emperor Hui of the Western Jin dynasty. As the capital of Jinchang Commandery (later Guazhou Prefecture), the city prospered during the Tang and Western Xia dynasties. It was an important administrative, economic, and cultural center of the Hexi Corridor for over a millennium, with an estimated peak population of 50,000. It was destroyed and abandoned in the 16th century, after the Ming dynasty came under attack by Mansur Khan of Moghulistan.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Outer wall of Suoyang City | |

| Location | Guazhou County, Gansu, China |

| Part of | Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iii), (vi) |

| Reference | 1442 |

| Inscription | 2014 (38th session) |

| Area | 15,788.6 ha (39,014 acres) |

| Coordinates | 40°14′47″N 96°12′19″E |

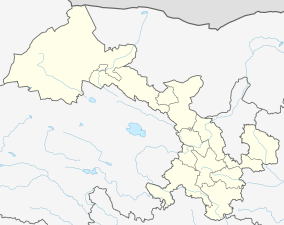

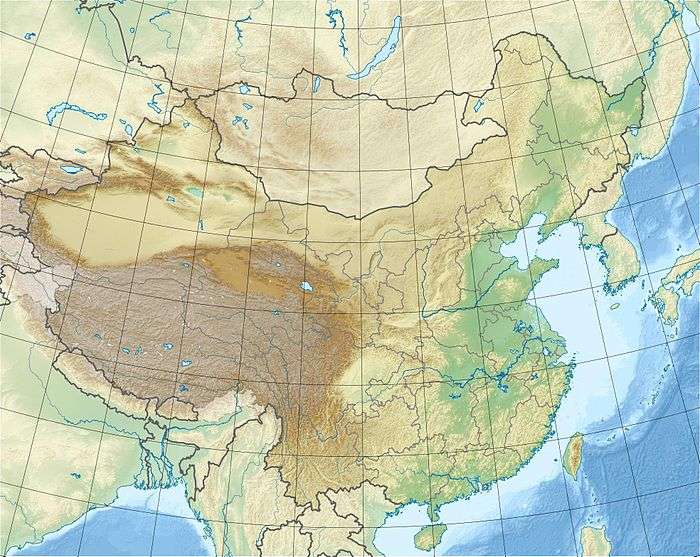

Location of Suoyang City in Gansu  Suoyang City (China) | |

The city ruins comprise the inner city, the outer city, and several yangmacheng (fortified animal enclosures used as fortresses in wartime). Outside the city walls, the broader archaeological park includes the original site of Ming'an County, more than 2,000 tombs, and the remains of an extensive irrigation system with over 90 kilometres (56 mi) of canals. The archaeological park also encompasses a number of Buddhist sites, including the Ta'er Temple, the Eastern Thousand Buddha Caves, Jianquanzi Caves (碱泉子石窟), and Hanxia Caves (旱峡石窟).[1]

Suoyang City is listed as a Major National Historical and Cultural Site of China (No. 4-50). In 2014, it was inscribed on UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites as part of Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor.

Location

Suoyang City is located in the Gobi Desert, southeast of modern Suoyangcheng Town, Guazhou County, in Gansu Province of Northwestern China. It occupies the site of an ancient oasis in the Hexi Corridor, at an altitude of 1,358 metres (4,455 ft) above sea level. During its existence of about 1,700 years, the city was a major political, military, economic and cultural center on the Silk Road, between Dunhuang (Shazhou) to the west and Jiuquan (Suzhou) to the east.[2]

City ruins

The walled city comprises an inner city, an outer city, and several yangmacheng fortresses in between.[2]

Inner city

The inner city is in the shape of an irregular rectangle measuring 285,000 square metres (3,070,000 sq ft) in area. Its four walls measure 493.6 metres (1,619 ft) (east), 576 metres (1,890 ft) (west), 457.3 metres (1,500 ft) (south), and 534 metres (1,752 ft) (north). The bases of the rammed earth walls are 19 metres (62 ft) wide, and the remaining walls are 9 to 12.5 m tall.[2]

Two main streets run through the western and northern gates, respectively, with many smaller streets and alleys branching from them. A partition wall divides the inner city into two sections: the larger western city and the smaller eastern city. Many house remains and thick layers of charcoal have been found in the western city, while the eastern city has few remains. It is likely that the eastern city housed the government buildings and residences of high-ranking officials, while the general populace lived in the western city. In the northwest corner of the inner city, an 18-metre (59 ft) tall adobe watchtower remains standing.[2]

Outer city

The outer city is also an irregular rectangle. Its walls measure 530.5 metres (1,740 ft) in the east, 649.9 metres (2,132 ft) in the west, and 1,178.6 metres (3,867 ft) in the north. The south wall is broken into two parts: a 497.6-metre (1,633 ft) eastern section, and a 452.8-metre (1,486 ft) western one. The bases of the outer city walls are between 4–6 metres (13–20 ft) wide, and the remaining walls are between 4–11 metres (13–36 ft) tall. The northern part of the outer city is divided from the rest by an internal wall north of the inner city.[2]

The outer city is believed to be the largest extent of Suoyang at its peak during the Tang dynasty. It was destroyed by floods coming from the mountains in the south, which breached the southern wall and cut it into two sections. Most buildings in the city were destroyed or damaged, the remains of which have been found in the outer city, covered by a 70-centimetre (28 in) thick layer of flood sediments. The outer city and the outer walls were not rebuilt or repaired after the destruction.[2]

Yangmacheng

Between the outer and inner cities are several fortresses known as yangmacheng (literally "sheep-and-horse city"). A common feature of Tang dynasty cities, they were used as animal enclosures in peace time to keep humans and livestock apart as a disease-prevention measure, and as military fortresses in wartime. There are no signs that the ones at Suoyang were repaired or used after the Tang dynasty.[2]

Outside the walled city

Ta'er Temple

1 kilometre (0.62 mi) east of the city are the remains of the Buddhist Ta'er Temple (literally "Pagoda Temple"), which is believed to be the King Ashoka Temple recorded in historical documents. It was destroyed in Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou's suppression of Buddhism and rebuilt in the Tang and Western Xia dynasties. It is said to be where the great Tang monk Xuanzang preached for a month before he left for his pilgrimage to India. Most of the extant ruins date from the Western Xia, including the main pagoda and eleven smaller ones.[3]

Tombs and cemeteries

Many tombs and cemeteries lie outside of the city, mainly to the south and southeast.[3] More than 2,100 tombs have been discovered,[4] dating from as early as the Han and mostly from the Tang dynasty.[3][4] They have not been excavated by archaeologists, with the notable exception of a large Tang tomb, which was excavated in 1992 after it was disturbed by tomb robbers.[3] Many Tang dynasty artifacts were found in the tomb, including sancai figurines and tomb guardians, silk, porcelain, and coins. One of the richest tombs found along the Silk Road, it probably belonged to a governor of Guazhou Prefecture or a wealthy merchant.[2][3]

Irrigation system

Ruins of an extensive system of irrigation canals remain outside of the city, which diverted water from the Shule River (called Ming River in the Han dynasty and Ku River in the Tang dynasty) for farming.[3] Approximately 90 kilometres (56 mi) of channels irrigated an area of 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi) of land surrounding Suoyang.[4] It is estimated that there was 300,000 mu of farmland in the Han and Tang dynasties. It is one of the most extensive undisturbed ancient irrigation systems in China and the world.[3]

History

In 111 BC, Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty established Ming'an County (冥安縣) under the Dunhuang Commandery. Its seat was located 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) northeast of Suoyang.[3] During the Western Jin dynasty, Emperor Hui established Jinchang Commandery (晉昌郡), which governed eight counties. Ming'an was elevated to become the capital of the new commandery, and a new city was built at the current site in 295 AD to serve as the commandery and county seat.[5][3]

After the fall of the Western Jin, Jinchang was controlled by a succession of short-lived kingdoms including Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, Southern Liang, Western Liang, and Northern Wei. During the Sui dynasty which reunited China, Ming'an was renamed Changle County (常樂縣). In 621, in the subsequent Tang dynasty, Jinchang Commandery was renamed Guazhou (Gua Prefecture), whereas Changle (Ming'an) was renamed Jinchang County, still serving as the prefectural seat.[3] The city's population during the Tang dynasty is estimated to be 50,000.[6]

As the Tang empire was severely weakened by the An Lushan rebellion, the city fell under the control of the Tibetan empire in 776, until it was recovered by the Tang loyalist general Zhang Yichao in 849.[3] After the collapse of the Tang, the Western Xia occupied Guazhou in 1036.[7] It became a major city of the Xia empire and the headquarters of its western military region. Emperor Li Renxiao, who was once based there, promoted Buddhism and built many cave temples nearby. After the Mongol Empire destroyed Western Xia in 1227, Guazhou Prefecture was not restored until fifty years later during the Yuan dynasty, when it was governed under Shazhou Circuit.[8]

During the Ming dynasty, the city was called Kuyu (苦峪), a name that was first recorded in 1405 in the Ming Shilu. When the king of Hami was threatened by the Mongols, the Chenghua Emperor of Ming moved him and his followers to Kuyu in 1472. In 1494, the Hongzhi Emperor repaired the city's walls that remained from the Tang and Western Xia eras. Two decades later, under attack by Mansur Khan, the Ming retreated east to the Jiayu Pass and Kuyu was occupied by Mansur. However, constant fighting among the Mongols, Moghulistan, and other nomadic tribes severely damaged the city and it was eventually abandoned.[3]

The name "Suoyang City" comes from the Qing dynasty novel Xue Rengui's Campaign to the West, based on the campaigns of the Tang dynasty general Xue Rengui.[3] In the novel and the popular legend it spawned, Xue's troops were besieged in the city by the Göktürks, and survived by eating the suoyang plant (Cynomorium songaricum) that grew wild in the city until reenforcement arrived. The ruined city subsequently became known as Suoyang City.[1]

Conservation

In 1996, the State Council of China designated Suoyang City as a Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level (No. 4-50).[9] The site was listed in 2010 by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage as a candidate for the national archaeological park status.[10] In 2014, Suoyang City was among the 33 sites inscribed on UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites as part of Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor.[11] The World Heritage Site property area covers 15,788.6 hectares (39,014 acres).[4]

References

- Hu, Shuangpeng (24 January 2015). "锁阳城:集多种遗迹为一体的罕见古遗址". People's Daily. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Yao, Xue (11 June 2012). "锁阳城遗址及墓群" [Suoyang City ruins and tombs]. Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Li Hongwei 李宏伟; Xie Yanming 谢延明 (16 September 2011). "锁阳城遗址形制及相关遗存初探" [A preliminary investigation on Suoyang City ruins and related sites]. The Silk Road (in Chinese). ISSN 1005-3115. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "The Site of Suoyang City Introduction". Silk Roads World Heritage Site. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Zhou (2014), p. 655.

- "A Forgotten Ancient City". China Radio International. 3 November 2014. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Li (2014), p. 9.

- Li (2014), p. 10.

- "国务院关于公布第四批全国重点文物保护单位的通知". State Council of China. 20 November 1996. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- "文物局公布首批国家考古遗址公园名单和立项名单" (in Chinese). State Administration of Cultural Heritage. 9 October 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- "Suoyang city added to World Heritage list". China Daily. 9 July 2014. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

Bibliography

- Li, Hongwei, ed. (2014). 瓜州锁阳城遗址 [The Suoyang City Ruins of Guazhou]. Xi'an: San Qin Publishing. ISBN 978-7-5518-0559-9. OCLC 871188507.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zhou, Zhenhe, ed. (2014). 中国行政区划通史 三国两晋南朝卷 [General History of Chinese Administrative Divisions: Three Kingdoms, Jin dynasty, and the Southern Dynasties] (1st ed.). Shanghai: Fudan University Press. ISBN 9787309055931. OCLC 187711320.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)