Structure formation

In physical cosmology, structure formation is the formation of galaxies, galaxy clusters and larger structures from small early density fluctuations. The universe, as is now known from observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation, began in a hot, dense, nearly uniform state approximately 13.8 billion years ago.[1] However, looking in the sky today, we see structures on all scales, from stars and planets to galaxies and, on still larger scales, galaxy clusters and sheet-like structures of galaxies separated by enormous voids containing few galaxies. Structure formation attempts to model how these structures formed by gravitational instability of small early density ripples.[2][3][4][5]

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Physical cosmology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Early universe

|

||||

|

Expansion · Future |

||||

|

Components · Structure

|

||||

| ||||

The modern Lambda-CDM model is successful at predicting the observed large-scale distribution of galaxies, clusters and voids; but on the scale of individual galaxies there are many complications due to highly nonlinear processes involving baryonic physics, gas heating and cooling, star formation and feedback. Understanding the processes of galaxy formation is a major topic of modern cosmology research, both via observations such as the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field and via large computer simulations.

Overview

Under present models, the structure of the visible universe was formed in the following stages:

Very early universe

In this stage, some mechanism, such as cosmic inflation, was responsible for establishing the initial conditions of the universe: homogeneity, isotropy, and flatness.[3][6] Cosmic inflation also would have amplified minute quantum fluctuations (pre-inflation) into slight density ripples of overdensity and underdensity (post-inflation).

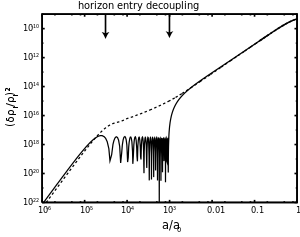

Growth of structure

The early universe was dominated by radiation; in this case density fluctuations larger than the cosmic horizon grow proportional to the scale factor, as the gravitational potential fluctuations remain constant. Structures smaller than the horizon remained essentially frozen due to radiation domination impeding growth. As the universe expanded, the density of radiation drops faster than matter (due to redshifting of photon energy); this led to a crossover called matter-radiation equality at ~ 50,000 years after the Big Bang. After this all dark matter ripples could grow freely, forming seeds into which the baryons could later fall. The size of the universe at this epoch forms a turnover in the matter power spectrum which can be measured in large redshift surveys.

Recombination

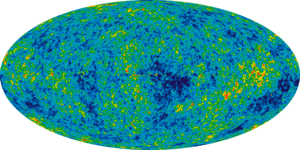

The universe was dominated by radiation for most of this stage, and due to the intense heat and radiation, the primordial hydrogen and helium were fully ionized into nuclei and free electrons. In this hot and dense situation, the radiation (photons) could not travel far before Thomson scattering off an electron. The universe was very hot and dense, but expanding rapidly and therefore cooling. Finally, at a little less than 400,000 years after the 'bang', it became cool enough (around 3000 K) for the protons to capture negatively charged electrons, forming neutral hydrogen atoms. (Helium atoms formed somewhat earlier due to their larger binding energy). Once nearly all the charged particles were bound in neutral atoms, the photons no longer interacted with them and were free to propagate for the next 13.8 billion years; we currently detect those photons redshifted by a factor 1090 down to 2.725 K as the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMB) filling today's universe. Several remarkable space-based missions (COBE, WMAP, Planck), have detected very slight variations in the density and temperature of the CMB. These variations were subtle, and the CMB appears very nearly uniformly the same in every direction. However, the slight temperature variations of order a few parts in 100,000 are of enormous importance, for they essentially were early "seeds" from which all subsequent complex structures in the universe ultimately developed.

The theory of what happened after the universe's first 400,000 years is one of hierarchical structure formation: the smaller gravitationally bound structures such as matter peaks containing the first stars and stellar clusters formed first, and these subsequently merged with gas and dark matter to form galaxies, followed by groups, clusters and superclusters of galaxies.

Very early universe

The very early universe is still a poorly understood epoch, from the viewpoint of fundamental physics. The prevailing theory, cosmic inflation, does a good job explaining the observed flatness, homogeneity and isotropy of the universe, as well as the absence of exotic relic particles (such as magnetic monopoles). Another prediction borne out by observation is that tiny perturbations in the primordial universe seed the later formation of structure. These fluctuations, while they form the foundation for all structure, appear most clearly as tiny temperature fluctuations at one part in 100,000. (To put this in perspective, the same level of fluctuations on a topographic map of the United States would show no feature taller than a few centimeters.) These fluctuations are critical, because they provide the seeds from which the largest structures can grow and eventually collapse to form galaxies and stars. COBE (Cosmic Background Explorer) provided the first detection of the intrinsic fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background radiation in the 1990s.

These perturbations are thought to have a very specific character: they form a Gaussian random field whose covariance function is diagonal and nearly scale-invariant. Observed fluctuations appear to have exactly this form, and in addition the spectral index measured by WMAP—the spectral index measures the deviation from a scale-invariant (or Harrison-Zel'dovich) spectrum—is very nearly the value predicted by the simplest and most robust models of inflation. Another important property of the primordial perturbations, that they are adiabatic (or isentropic between the various kinds of matter that compose the universe), is predicted by cosmic inflation and has been confirmed by observations.

Other theories of the very early universe have been proposed that are claimed to make similar predictions, such as the brane gas cosmology, cyclic model, pre-big bang model and holographic universe, but they remain nascent and are not widely accepted. Some theories, such as cosmic strings, have largely been refuted by increasingly precise data.

The horizon problem

An important concept in structure formation is the notion of the Hubble radius, often called simply the horizon, as it is closely related to the particle horizon. The Hubble radius, which is related to the Hubble parameter as , where is the speed of light, defines, roughly speaking, the volume of the nearby universe that has recently (in the last expansion time) been in causal contact with an observer. Since the universe is continually expanding, its energy density is continually decreasing (in the absence of truly exotic matter such as phantom energy). The Friedmann equation relates the energy density of the universe to the Hubble parameter and shows that the Hubble radius is continually increasing.

The horizon problem of big bang cosmology says that, without inflation, perturbations were never in causal contact before they entered the horizon and thus the homogeneity and isotropy of, for example, the large scale galaxy distributions cannot be explained. This is because, in an ordinary Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker cosmology, the Hubble radius increases more rapidly than space expands, so perturbations only enter the Hubble radius, and are not pushed out by the expansion. This paradox is resolved by cosmic inflation, which suggests that during a phase of rapid expansion in the early universe the Hubble radius was nearly constant. Thus, large scale isotropy is due to quantum fluctuations produced during cosmic inflation that are pushed outside the horizon.

Primordial plasma

The end of inflation is called reheating, when the inflation particles decay into a hot, thermal plasma of other particles. In this epoch, the energy content of the universe is entirely radiation, with standard model particles having relativistic velocities. As the plasma cools, baryogenesis and leptogenesis are thought to occur, as the quark–gluon plasma cools, electroweak symmetry breaking occurs and the universe becomes principally composed of ordinary protons, neutrons and electrons. As the universe cools further, Big Bang nucleosynthesis occurs and small quantities of deuterium, helium and lithium nuclei are created. As the universe cools and expands, the energy in photons begins to redshift away, particles become non-relativistic and ordinary matter begins to dominate the universe. Eventually, atoms begin to form as free electrons bind to nuclei. This suppresses Thomson scattering of photons. Combined with the rarefaction of the universe (and consequent increase in the mean free path of photons), this makes the universe transparent and the cosmic microwave background is emitted at recombination (the surface of last scattering).

Acoustic oscillations

The primordial plasma would have had very slight overdensities of matter, thought to have derived from the enlargement of quantum fluctuations during inflation. Whatever the source, these overdensities gravitationally attract matter. But the intense heat of the near constant photon-matter interactions of this epoch rather forcefully seeks thermal equilibrium, which creates a large amount of outward pressure. These counteracting forces of gravity and pressure create oscillations, analogous to sound waves created in air by pressure differences.

These perturbations are important, as they are responsible for the subtle physics that result in the cosmic microwave background anisotropy. In this epoch, the amplitude of perturbations that enter the horizon oscillate sinusoidally, with dense regions becoming more rarefied and then becoming dense again, with a frequency which is related to the size of the perturbation. If the perturbation oscillates an integral or half-integral number of times between coming into the horizon and recombination, it appears as an acoustic peak of the cosmic microwave background anisotropy. (A half-oscillation, in which a dense region becomes a rarefied region or vice versa, appears as a peak because the anisotropy is displayed as a power spectrum, so underdensities contribute to the power just as much as overdensities.) The physics that determines the detailed peak structure of the microwave background is complicated, but these oscillations provide the essence.[7][8][9][10][11]

Linear structure

One of the key realizations made by cosmologists in the 1970s and 1980s was that the majority of the matter content of the universe was composed not of atoms, but rather a mysterious form of matter known as dark matter. Dark matter interacts through the force of gravity, but it is not composed of baryons, and it is known with very high accuracy that it does not emit or absorb radiation. It may be composed of particles that interact through the weak interaction, such as neutrinos,[12] but it cannot be composed entirely of the three known kinds of neutrinos (although some have suggested it is a sterile neutrino). Recent evidence indicates that there are about five times as much dark matter as baryonic matter, and thus the dynamics of the universe in this epoch are dominated by dark matter.

Dark matter plays a crucial role in structure formation because it feels only the force of gravity: the gravitational Jeans instability which allows compact structures to form is not opposed by any force, such as radiation pressure. As a result, dark matter begins to collapse into a complex network of dark matter halos well before ordinary matter, which is impeded by pressure forces. Without dark matter, the epoch of galaxy formation would occur substantially later in the universe than is observed.

The physics of structure formation in this epoch is particularly simple, as dark matter perturbations with different wavelengths evolve independently. As the Hubble radius grows in the expanding universe, it encompasses larger and larger disturbances. During matter domination, all causal dark matter perturbations grow through gravitational clustering. However, the shorter-wavelength perturbations that are included during radiation domination have their growth retarded until matter domination. At this stage, luminous, baryonic matter is expected to mirror the evolution of the dark matter simply, and their distributions should closely trace one another.

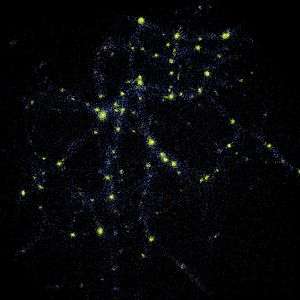

It is straightforward to calculate this "linear power spectrum" and, as a tool for cosmology, it is of comparable importance to the cosmic microwave background. Galaxy surveys have measured the power spectrum, such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, and by surveys of the Lyman-α forest. Since these studies observe radiation emitted from galaxies and quasars, they do not directly measure the dark matter, but the large-scale distribution of galaxies (and of absorption lines in the Lyman-α forest) is expected to mirror the distribution of dark matter closely. This depends on the fact that galaxies will be larger and more numerous in denser parts of the universe, whereas they will be comparatively scarce in rarefied regions.

Nonlinear structure

When the perturbations have grown sufficiently, a small region might become substantially denser than the mean density of the universe. At this point, the physics involved becomes substantially more complicated. When the deviations from homogeneity are small, the dark matter may be treated as a pressureless fluid and evolves by very simple equations. In regions which are significantly denser than the background, the full Newtonian theory of gravity must be included. (The Newtonian theory is appropriate because the masses involved are much less than those required to form a black hole, and the speed of gravity may be ignored as the light-crossing time for the structure is still smaller than the characteristic dynamical time.) One sign that the linear and fluid approximations become invalid is that dark matter starts to form caustics in which the trajectories of adjacent particles cross, or particles start to form orbits. These dynamics are best understood using N-body simulations (although a variety of semi-analytic schemes, such as the Press–Schechter formalism, can be used in some cases). While in principle these simulations are quite simple, in practice they are tough to implement, as they require simulating millions or even billions of particles. Moreover, despite the large number of particles, each particle typically weighs 109 solar masses and discretization effects may become significant. The largest such simulation as of 2005 is the Millennium simulation.[13]

The result of N-body simulations suggests that the universe is composed largely of voids, whose densities might be as low as one-tenth the cosmological mean. The matter condenses in large filaments and haloes which have an intricate web-like structure. These form galaxy groups, clusters and superclusters. While the simulations appear to agree broadly with observations, their interpretation is complicated by the understanding of how dense accumulations of dark matter spur galaxy formation. In particular, many more small haloes form than we see in astronomical observations as dwarf galaxies and globular clusters. This is known as the galaxy bias problem, and a variety of explanations have been proposed. Most account for it as an effect in the complicated physics of galaxy formation, but some have suggested that it is a problem with our model of dark matter and that some effect, such as warm dark matter, prevents the formation of the smallest haloes.

Gas evolution

The final stage in evolution comes when baryons condense in the centres of galaxy haloes to form galaxies, stars and quasars. Dark matter greatly accelerates the formation of dense haloes. As dark matter does not have radiation pressure, the formation of smaller structures from dark matter is impossible. This is because dark matter cannot dissipate angular momentum, whereas ordinary baryonic matter can collapse to form dense objects by dissipating angular momentum through radiative cooling. Understanding these processes is an enormously difficult computational problem, because they can involve the physics of gravity, magnetohydrodynamics, atomic physics, nuclear reactions, turbulence and even general relativity. In most cases, it is not yet possible to perform simulations that can be compared quantitatively with observations, and the best that can be achieved are approximate simulations that illustrate the main qualitative features of a process such as a star formation.

Modelling structure formation

Cosmological perturbations

Much of the difficulty, and many of the disputes, in understanding the large-scale structure of the universe can be resolved by better understanding the choice of gauge in general relativity. By the scalar-vector-tensor decomposition, the metric includes four scalar perturbations, two vector perturbations, and one tensor perturbation. Only the scalar perturbations are significant: the vectors are exponentially suppressed in the early universe, and the tensor mode makes only a small (but important) contribution in the form of primordial gravitational radiation and the B-modes of the cosmic microwave background polarization. Two of the four scalar modes may be removed by a physically meaningless coordinate transformation. Which modes are eliminated determine the infinite number of possible gauge fixings. The most popular gauge is Newtonian gauge (and the closely related conformal Newtonian gauge), in which the retained scalars are the Newtonian potentials Φ and Ψ, which correspond exactly to the Newtonian potential energy from Newtonian gravity. Many other gauges are used, including synchronous gauge, which can be an efficient gauge for numerical computation (it is used by CMBFAST). Each gauge still includes some unphysical degrees of freedom. There is a so-called gauge-invariant formalism, in which only gauge invariant combinations of variables are considered.

Inflation and initial conditions

The initial conditions for the universe are thought to arise from the scale invariant quantum mechanical fluctuations of cosmic inflation. The perturbation of the background energy density at a given point in space is then given by an isotropic, homogeneous Gaussian random field of mean zero. This means that the spatial Fourier transform of – has the following correlation functions

- ,

where is the three-dimensional Dirac delta function and is the length of . Moreover, the spectrum predicted by inflation is nearly scale invariant, which means

- ,

where is a small number. Finally, the initial conditions are adiabatic or isentropic, which means that the fractional perturbation in the entropy of each species of particle is equal. The resulting predictions fit very well with observations, however there is a conceptual problem with the physical picture presented above. The quantum state from which the quantum fluctuations are extracted, is in fact completely homogeneous and isotropic, and thus it can not be argued that the quantum fluctuations represent the primordial inhomogeneities and anisotropies. The interpretation of quantum uncertainties in the value of the inflation field (which is what the so-called quantum fluctuations really are) as if they were statistical fluctuations in a Gaussian random field does not follow from the application of standard rules of quantum theory. The issue is sometimes presented in terms of the "quantum to classical transition", which is a confusing manner to refer to the problem at hand, as there are very few physicists, if any, that would argue that there is any entity that is truly classical at the fundamental level. In fact, the consideration of these issues brings us face to face with the so called measurement problem in quantum theory. If anything, the problem becomes exacerbated in the cosmological context, as the early universe contains no entities that might be taken as playing the role of "observers" or of "measuring devices", both of which are essential for the standard usage of quantum mechanics.[14] The most popular posture among cosmologists, in this regard, is to rely on arguments based on decoherence and some form of "Many Worlds Interpretation" of quantum theory. There is an intense ongoing debate about the reasonableness of that posture [15] .[16]

See also

- Big Bang – Cosmological model

- Chronology of the universe – Events since the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago

- Galaxy formation and evolution – Processes that formed a heterogeneous universe from a homogeneous beginning, the formation of the first galaxies, the way galaxies change over time

- Illustris project – Computer-simulated universes

- Stellar evolution – Changes to a star over its lifespan

- Timeline of the Big Bang

References

- "Cosmic Detectives". The European Space Agency (ESA). 2013-04-02. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- Dodelson, Scott (2003). Modern Cosmology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-219141-1.

- Liddle, Andrew; David Lyth (2000). Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-57598-0.

- Padmanabhan, T. (1993). Structure formation in the universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42486-8.

- Peebles, P. J. E. (1980). The Large-Scale Structure of the Universe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08240-0.

- Kolb, Edward; Michael Turner (1988). The Early Universe. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-11604-5.

- Harrison, E. R. (1970). "Fluctuations at the threshold of classical cosmology". Phys. Rev. D1 (10): 2726. Bibcode:1970PhRvD...1.2726H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.1.2726.

- Peebles, P. J. E.; Yu, J. T. (1970). "Primeval adiabatic perturbation in an expanding universe". Astrophysical Journal. 162: 815. Bibcode:1970ApJ...162..815P. doi:10.1086/150713.

- Zel'dovich, Yaa B. (1972). "A hypothesis, unifying the structure and entropy of the Universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 160: 1P–3P. Bibcode:1972MNRAS.160P...1Z. doi:10.1093/mnras/160.1.1p.

- R. A. Sunyaev, "Fluctuations of the microwave background radiation", in Large Scale Structure of the Universe ed. M. S. Longair and J. Einasto, 393. Dordrecht: Reidel 1978.

- U. Seljak & M. Zaldarriaga (1996). "A line-of-sight integration approach to cosmic microwave background anisotropies". Astrophys. J. 469: 437–444. arXiv:astro-ph/9603033. Bibcode:1996ApJ...469..437S. doi:10.1086/177793.

- Overbye, Dennis (15 April 2020). "Why The Big Bang Produced Something Rather Than Nothing - How did matter gain the edge over antimatter in the early universe? Maybe, just maybe, neutrinos". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Springel, V.; et al. (2005). "Simulations of the formation, evolution and clustering of galaxies and quasars". Nature. 435 (7042): 629–636. arXiv:astro-ph/0504097. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..629S. doi:10.1038/nature03597. PMID 15931216.

- A. Perez; H. Sahlmann & D. Sudarsky (2006). "On the Quantum Mechanical Origin of the Seeds of Cosmic Structure". Class. Quantum Grav. 23 (7): 2317–2354. arXiv:gr-qc/0508100. Bibcode:2006CQGra..23.2317P. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/23/7/008.

- C. Kiefer & David Polarski (2009). "Why do cosmological perturbations look classical to us?". Adv. Sci. Lett. 2 (2): 164–173. arXiv:0810.0087. Bibcode:2008arXiv0810.0087K. doi:10.1166/asl.2009.1023.

- D. Sudarsky (2011). "Shortcomings in the Understanding of Why Cosmological Perturbations Look Classical". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 2o (4): 509–552. arXiv:0906.0315. Bibcode:2011IJMPD..20..509S. doi:10.1142/S0218271811018937.