Richard C. Tolman

Richard Chace Tolman (March 4, 1881 – September 5, 1948) was an American mathematical physicist and physical chemist who made many contributions to statistical mechanics.[1] He also made important contributions to theoretical cosmology in the years soon after Einstein's discovery of general relativity. He was a professor of physical chemistry and mathematical physics at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

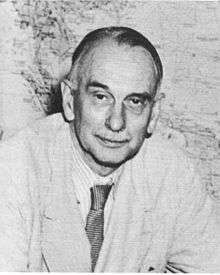

Richard C. Tolman | |

|---|---|

Richard C. Tolman in 1945 | |

| Born | March 4, 1881 West Newton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 5, 1948 (aged 67) Pasadena, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physical chemistry Statistical Mechanics Cosmology |

| Institutions | California Institute of Technology |

| Thesis | The Electromotive Force Produced in Solutions by Centrifugal Action (1910) |

| Doctoral advisor | Arthur Amos Noyes |

| Doctoral students | Allan C. G. Mitchell Linus Pauling |

Biography

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Physical cosmology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Early universe

|

||||

|

Expansion · Future |

||||

|

Components · Structure

|

||||

| ||||

Tolman was born in West Newton, Massachusetts and studied chemical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, receiving his bachelor's degree in 1903 and Ph.D. in 1910 under A. A. Noyes.[2]

He married Ruth Sherman Tolman in 1924.

In 1912, he conceived of the concept of relativistic mass, writing that "the expression is best suited for the mass of a moving body."[3]

In a 1916 experiment with Thomas Dale Stewart, Tolman demonstrated that electricity consists of electrons flowing through a metallic conductor. A by-product of this experiment was a measured value of the mass of the electron.[4] Overall, however, he was primarily known as a theorist.

Tolman was a member of the Technical Alliance in 1919, a forerunner of the Technocracy movement where he helped conduct an energy survey analyzing the possibility of applying science to social and industrial affairs.[5][6][7]

Tolman was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1922.[8] The same year, he joined the faculty of the California Institute of Technology, where he became professor of physical chemistry and mathematical physics and later dean of the graduate school. One of Tolman's early students at Caltech was the theoretical chemist Linus Pauling, to whom Tolman taught the old quantum theory.

In 1927, Tolman published a text on statistical mechanics whose background was the old quantum theory of Max Planck, Niels Bohr and Arnold Sommerfeld.[9] In 1938, he published a new detailed work that covered the application of statistical mechanics to classical and quantum systems.[10][11] It was the standard work on the subject for many years and remains of interest today.

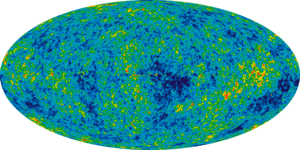

In the later years of his career, Tolman became increasingly interested in the application of thermodynamics to relativistic systems and cosmology. An important monograph he published in 1934 titled Relativity, Thermodynamics, and Cosmology[12] demonstrated how black body radiation in an expanding universe cools but remains thermal – a key pointer toward the properties of the cosmic microwave background.[13] Also in this monograph, Tolman was the first person to document and explain how a closed universe could equal zero energy. He explained how all mass energy is positive and all gravitational energy is negative and they cancel each other out, leading to a universe of zero energy.[13] His investigation of the oscillatory universe hypothesis, which Alexander Friedmann had proposed in 1922, drew attention to difficulties as regards entropy and resulted in its demise until the late 1960s.

During World War II, Tolman served as scientific advisor to General Leslie Groves on the Manhattan Project. At the time of his death in Pasadena, he was chief advisor to Bernard Baruch, the U.S. representative to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission.

Each year, the southern California section of the American Chemical Society honors Tolman by awarding its Tolman Medal "in recognition of outstanding contributions to chemistry."

Family

Tolman's brother was the behavioral psychologist Edward Chace Tolman.

See also

References

- Gale, George (2014), "Tolman, Richard Chace", Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, New York, NY: Springer New York, pp. 2164–2165, ISBN 978-1-4419-9916-0, retrieved 2020-06-19

- Richard C. Tolman at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Tolman, R. C. (1912). "Non-Newtonian Mechanics, The Mass of a Moving Body". Philosophical Magazine. 23 (135): 375–381. doi:10.1080/14786440308637231.

- Tolman, R. C.; Stewart, T. D. (1916). "The electromotive force produced by the acceleration of metals". Physical Review. 8 (2): 97–116. Bibcode:1916PhRv....8...97T. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.8.97. PMC 1090978. PMID 16576140.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-12-21. Retrieved 2013-03-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Retrieved March-16-13

- Anderson, Larry (2002). Benton MacKaye: Conservationist, planner, and creator of the Appalachian Trail. JHU Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780801869020. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Anderson, Larry (2002). Benton MacKaye: Conservationist, planner, and creator of the Appalachian Trail. JHU Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780226465838. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter T" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- Bartky, W. (1927). "Review: Statistical Mechanics with Applications to Physics and Chemistry by Richard C. Tolman". Astrophysical Journal. 66: 143–144. Bibcode:1927ApJ....66..143B. doi:10.1086/143076.

- Sterne, Theodore E. (1941). "Review: The Principles of Statistical Mechanics by Richard C. Tolman". Astrophysical Journal. 93: 513. Bibcode:1941ApJ....93..513.. doi:10.1086/144301.

- Infeld, L. (July 1939). "Review: The Principles of Statistical Mechanics by Richard C. Tolman". Philosophy of Science. 6 (3): 381. doi:10.1086/286579.

- Chant, C. A. (1934). "Review: Relativity, Thermodynamics, and Cosmology by Richard C. Tolman". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 28: 324–325. Bibcode:1934JRASC..28Q.324C.

- Reynosa, Peter (2016-03-16). "Why Isn't Edward P. Tryon A World-famous Physicist?". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 22, 2016. (See Edward Tryon.)

Books by Tolman

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Richard C. Tolman |

- Statistical mechanics with applications to physics and chemistry. New York: The Chemical Catalog Company. 1927.

- Relativity, Thermodynamics, and Cosmology. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1934. LCCN 34032023. Reissued (1987) New York: Dover ISBN 0-486-65383-8.

- The Principles of Statistical Mechanics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1938. ISBN 9780486638966. Reissued (1979) New York: Dover ISBN 0-486-63896-0. Tolman, Richard Chace (January 1987). 1987 Dover reprint. ISBN 9780486653839.

External links

- Short biography from the Online Archive of California

- Short biography from the "Tolman Award" page of the Southern California Section of the American Chemical Society.

- Works by Richard C. Tolman at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Richard C. Tolman at Internet Archive

- Biographical memoir, National Academy of Sciences. Includes a complete bibliography of Tolman's writings. Retrieved July 14, 2017.