Lambda-CDM model

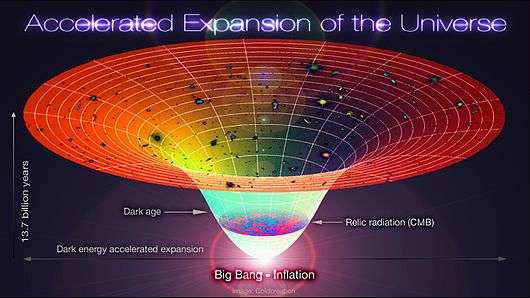

The ΛCDM (Lambda cold dark matter) or Lambda-CDM model is a parametrization of the Big Bang cosmological model in which the universe contains three major components: first, a cosmological constant denoted by Lambda (Greek Λ) and associated with dark energy; second, the postulated cold dark matter (abbreviated CDM); and third, ordinary matter. It is frequently referred to as the standard model of Big Bang cosmology because it is the simplest model that provides a reasonably good account of the following properties of the cosmos:

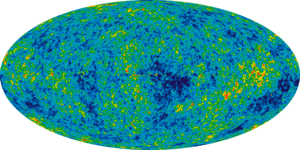

- the existence and structure of the cosmic microwave background

- the large-scale structure in the distribution of galaxies

- the observed abundances of hydrogen (including deuterium), helium, and lithium

- the accelerating expansion of the universe observed in the light from distant galaxies and supernovae

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Physical cosmology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Early universe

|

||||

|

Expansion · Future |

||||

|

Components · Structure

|

||||

| ||||

The model assumes that general relativity is the correct theory of gravity on cosmological scales. It emerged in the late 1990s as a concordance cosmology, after a period of time when disparate observed properties of the universe appeared mutually inconsistent, and there was no consensus on the makeup of the energy density of the universe.

The ΛCDM model can be extended by adding cosmological inflation, quintessence and other elements that are current areas of speculation and research in cosmology.

Some alternative models challenge the assumptions of the ΛCDM model. Examples of these are modified Newtonian dynamics, entropic gravity, modified gravity, theories of large-scale variations in the matter density of the universe, bimetric gravity, scale invariance of empty space, and decaying dark matter (DDM).[1][2][3][4][5]

Overview

Most modern cosmological models are based on the cosmological principle, which states that our observational location in the universe is not unusual or special; on a large-enough scale, the universe looks the same in all directions (isotropy) and from every location (homogeneity).[6]

The model includes an expansion of metric space that is well documented both as the red shift of prominent spectral absorption or emission lines in the light from distant galaxies and as the time dilation in the light decay of supernova luminosity curves. Both effects are attributed to a Doppler shift in electromagnetic radiation as it travels across expanding space. Although this expansion increases the distance between objects that are not under shared gravitational influence, it does not increase the size of the objects (e.g. galaxies) in space. It also allows for distant galaxies to recede from each other at speeds greater than the speed of light; local expansion is less than the speed of light, but expansion summed across great distances can collectively exceed the speed of light.

The letter (lambda) represents the cosmological constant, which is currently associated with a vacuum energy or dark energy in empty space that is used to explain the contemporary accelerating expansion of space against the attractive effects of gravity. A cosmological constant has negative pressure, , which contributes to the stress-energy tensor that, according to the general theory of relativity, causes accelerating expansion. The fraction of the total energy density of our (flat or almost flat) universe that is dark energy, , is estimated to be 0.669 ± 0.038 based on the 2018 Dark Energy Survey results using Type Ia Supernovae[7] or 0.6847 ± 0.0073 based on the 2018 release of Planck satellite data, or more than 68.3% (2018 estimate) of the mass-energy density of the universe.[8]

Dark matter is postulated in order to account for gravitational effects observed in very large-scale structures (the "flat" rotation curves of galaxies; the gravitational lensing of light by galaxy clusters; and enhanced clustering of galaxies) that cannot be accounted for by the quantity of observed matter.

Cold dark matter as currently hypothesized is:

- non-baryonic

- It consists of matter other than protons and neutrons (and electrons, by convention, although electrons are not baryons).

- cold

- Its velocity is far less than the speed of light at the epoch of radiation-matter equality (thus neutrinos are excluded, being non-baryonic but not cold).

- dissipationless

- It cannot cool by radiating photons.

- collisionless

- The dark matter particles interact with each other and other particles only through gravity and possibly the weak force.

Dark matter constitutes about 26.5%[9] of the mass-energy density of the universe. The remaining 4.9%[9] comprises all ordinary matter observed as atoms, chemical elements, gas and plasma, the stuff of which visible planets, stars and galaxies are made. The great majority of ordinary matter in the universe is unseen, since visible stars and gas inside galaxies and clusters account for less than 10% of the ordinary matter contribution to the mass-energy density of the universe.[10]

Also, the energy density includes a very small fraction (~ 0.01%) in cosmic microwave background radiation, and not more than 0.5% in relic neutrinos. Although very small today, these were much more important in the distant past, dominating the matter at redshift > 3200.

The model includes a single originating event, the "Big Bang", which was not an explosion but the abrupt appearance of expanding space-time containing radiation at temperatures of around 1015 K. This was immediately (within 10−29 seconds) followed by an exponential expansion of space by a scale multiplier of 1027 or more, known as cosmic inflation. The early universe remained hot (above 10,000 K) for several hundred thousand years, a state that is detectable as a residual cosmic microwave background, or CMB, a very low energy radiation emanating from all parts of the sky. The "Big Bang" scenario, with cosmic inflation and standard particle physics, is the only current cosmological model consistent with the observed continuing expansion of space, the observed distribution of lighter elements in the universe (hydrogen, helium, and lithium), and the spatial texture of minute irregularities (anisotropies) in the CMB radiation. Cosmic inflation also addresses the "horizon problem" in the CMB; indeed, it seems likely that the universe is larger than the observable particle horizon.

The model uses the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric, the Friedmann equations and the cosmological equations of state to describe the observable universe from right after the inflationary epoch to present and future.

Cosmic expansion history

The expansion of the universe is parameterized by a dimensionless scale factor (with time counted from the birth of the universe), defined relative to the present day, so ; the usual convention in cosmology is that subscript 0 denotes present-day values, so is the current age of the universe. The scale factor is related to the observed redshift[11] of the light emitted at time by

The expansion rate is described by the time-dependent Hubble parameter, , defined as

where is the time-derivative of the scale factor. The first Friedmann equation gives the expansion rate in terms of the matter+radiation density , the curvature , and the cosmological constant ,[11]

where as usual is the speed of light and is the gravitational constant. A critical density is the present-day density, which gives zero curvature , assuming the cosmological constant is zero, regardless of its actual value. Substituting these conditions to the Friedmann equation gives

where is the reduced Hubble constant. If the cosmological constant were actually zero, the critical density would also mark the dividing line between eventual recollapse of the universe to a Big Crunch, or unlimited expansion. For the Lambda-CDM model with a positive cosmological constant (as observed), the universe is predicted to expand forever regardless of whether the total density is slightly above or below the critical density; though other outcomes are possible in extended models where the dark energy is not constant but actually time-dependent.

It is standard to define the present-day density parameter for various species as the dimensionless ratio

where the subscript is one of for baryons, for cold dark matter, for radiation (photons plus relativistic neutrinos), and or for dark energy.

Since the densities of various species scale as different powers of , e.g. for matter etc., the Friedmann equation can be conveniently rewritten in terms of the various density parameters as

where is the equation of state parameter of dark energy, and assuming negligible neutrino mass (significant neutrino mass requires a more complex equation). The various parameters add up to by construction. In the general case this is integrated by computer to give the expansion history and also observable distance-redshift relations for any chosen values of the cosmological parameters, which can then be compared with observations such as supernovae and baryon acoustic oscillations.

In the minimal 6-parameter Lambda-CDM model, it is assumed that curvature is zero and , so this simplifies to

Observations show that the radiation density is very small today, ; if this term is neglected the above has an analytic solution[13]

where this is fairly accurate for or million years. Solving for gives the present age of the universe in terms of the other parameters.

It follows that the transition from decelerating to accelerating expansion (the second derivative crossing zero) occurred when

which evaluates to or for the best-fit parameters estimated from the Planck spacecraft.

Historical development

The discovery of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) in 1964 confirmed a key prediction of the Big Bang cosmology. From that point on, it was generally accepted that the universe started in a hot, dense state and has been expanding over time. The rate of expansion depends on the types of matter and energy present in the universe, and in particular, whether the total density is above or below the so-called critical density.

During the 1970s, most attention focused on pure-baryonic models, but there were serious challenges explaining the formation of galaxies, given the small anisotropies in the CMB (upper limits at that time). In the early 1980s, it was realized that this could be resolved if cold dark matter dominated over the baryons, and the theory of cosmic inflation motivated models with critical density.

During the 1980s, most research focused on cold dark matter with critical density in matter, around 95% CDM and 5% baryons: these showed success at forming galaxies and clusters of galaxies, but problems remained; notably, the model required a Hubble constant lower than preferred by observations, and observations around 1988–1990 showed more large-scale galaxy clustering than predicted.

These difficulties sharpened with the discovery of CMB anisotropy by the Cosmic Background Explorer in 1992, and several modified CDM models, including ΛCDM and mixed cold and hot dark matter, came under active consideration through the mid-1990s. The ΛCDM model then became the leading model following the observations of accelerating expansion in 1998, and was quickly supported by other observations: in 2000, the BOOMERanG microwave background experiment measured the total (matter–energy) density to be close to 100% of critical, whereas in 2001 the 2dFGRS galaxy redshift survey measured the matter density to be near 25%; the large difference between these values supports a positive Λ or dark energy. Much more precise spacecraft measurements of the microwave background from WMAP in 2003–2010 and Planck in 2013–2015 have continued to support the model and pin down the parameter values, most of which are now constrained below 1 percent uncertainty.

There is currently active research into many aspects of the ΛCDM model, both to refine the parameters and possibly detect deviations. In addition, ΛCDM has no explicit physical theory for the origin or physical nature of dark matter or dark energy; the nearly scale-invariant spectrum of the CMB perturbations, and their image across the celestial sphere, are believed to result from very small thermal and acoustic irregularities at the point of recombination.

A large majority of astronomers and astrophysicists support the ΛCDM model or close relatives of it, but Milgrom, McGaugh, and Kroupa are leading critics, attacking the dark matter portions of the theory from the perspective of galaxy formation models and supporting the alternative modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND) theory, which requires a modification of the Einstein field equations and the Friedmann equations as seen in proposals such as modified gravity theory (MOG theory) or tensor–vector–scalar gravity theory (TeVeS theory). Other proposals by theoretical astrophysicists of cosmological alternatives to Einstein's general relativity that attempt to account for dark energy or dark matter include f(R) gravity, scalar–tensor theories such as galileon theories, brane cosmologies, the DGP model, and massive gravity and its extensions such as bimetric gravity.

Successes

In addition to explaining pre-2000 observations, the model has made a number of successful predictions: notably the existence of the baryon acoustic oscillation feature, discovered in 2005 in the predicted location; and the statistics of weak gravitational lensing, first observed in 2000 by several teams. The polarization of the CMB, discovered in 2002 by DASI,[14] is now a dramatic success: in the 2015 Planck data release,[15] there are seven observed peaks in the temperature (TT) power spectrum, six peaks in the temperature-polarization (TE) cross spectrum, and five peaks in the polarization (EE) spectrum. The six free parameters can be well constrained by the TT spectrum alone, and then the TE and EE spectra can be predicted theoretically to few-percent precision with no further adjustments allowed: comparison of theory and observations shows an excellent match.

Challenges

Extensive searches for dark matter particles have so far shown no well-agreed detection; the dark energy may be almost impossible to detect in a laboratory, and its value is unnaturally small compared to naive theoretical predictions.

Comparison of the model with observations is very successful on large scales (larger than galaxies, up to the observable horizon), but may have some problems on sub-galaxy scales, possibly predicting too many dwarf galaxies and too much dark matter in the innermost regions of galaxies. This problem is called the "small scale crisis".[16] These small scales are harder to resolve in computer simulations, so it is not yet clear whether the problem is the simulations, non-standard properties of dark matter, or a more radical error in the model.

It has been argued that the ΛCDM model is built upon a foundation of conventionalist stratagems, rendering it unfalsifiable in the sense defined by Karl Popper.[17]

Parameters

| Description | Symbol | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indepen- dent para- meters |

Physical baryon density parameter[lower-alpha 1] | Ωb h2 | 0.02230±0.00014 |

| Physical dark matter density parameter[lower-alpha 1] | Ωc h2 | 0.1188±0.0010 | |

| Age of the universe | t0 | 13.799±0.021 × 109 years | |

| Scalar spectral index | ns | 0.9667±0.0040 | |

| Curvature fluctuation amplitude, k0 = 0.002 Mpc−1 |

2.441+0.088 −0.092×10−9[22] | ||

| Reionization optical depth | τ | 0.066±0.012 | |

| Fixed para- meters |

Total density parameter[lower-alpha 2] | Ωtot | 1 |

| Equation of state of dark energy | w | −1 | |

| Tensor/scalar ratio | r | 0 | |

| Running of spectral index | 0 | ||

| Sum of three neutrino masses | 0.06 eV/c2[lower-alpha 3][18]:40 | ||

| Effective number of relativistic degrees of freedom |

Neff | 3.046[lower-alpha 4][18]:47 | |

| Calcu- lated values |

Hubble constant | H0 | 67.74±0.46 km s−1 Mpc−1 |

| Baryon density parameter[lower-alpha 2] | Ωb | 0.0486±0.0010[lower-alpha 5] | |

| Dark matter density parameter[lower-alpha 2] | Ωc | 0.2589±0.0057[lower-alpha 6] | |

| Matter density parameter[lower-alpha 2] | Ωm | 0.3089±0.0062 | |

| Dark energy density parameter[lower-alpha 2] | ΩΛ | 0.6911±0.0062 | |

| Critical density | ρcrit | (8.62±0.12)×10−27 kg/m3[lower-alpha 7] | |

| The present root-mean-square matter fluctuation

averaged over a sphere of radius 8h–1 Mpc |

σ8 | 0.8159±0.0086 | |

| Redshift at decoupling | z∗ | 1089.90±0.23 | |

| Age at decoupling | t∗ | 377700±3200 years[22] | |

| Redshift of reionization (with uniform prior) | zre | 8.5+1.0 −1.1[23] |

The simple ΛCDM model is based on six parameters: physical baryon density parameter; physical dark matter density parameter; the age of the universe; scalar spectral index; curvature fluctuation amplitude; and reionization optical depth.[24] In accordance with Occam's razor, six is the smallest number of parameters needed to give an acceptable fit to current observations; other possible parameters are fixed at "natural" values, e.g. total density parameter = 1.00, dark energy equation of state = −1. (See below for extended models that allow these to vary.)

The values of these six parameters are mostly not predicted by current theory (though, ideally, they may be related by a future "Theory of Everything"), except that most versions of cosmic inflation predict the scalar spectral index should be slightly smaller than 1, consistent with the estimated value 0.96. The parameter values, and uncertainties, are estimated using large computer searches to locate the region of parameter space providing an acceptable match to cosmological observations. From these six parameters, the other model values, such as the Hubble constant and the dark energy density, can be readily calculated.

Commonly, the set of observations fitted includes the cosmic microwave background anisotropy, the brightness/redshift relation for supernovae, and large-scale galaxy clustering including the baryon acoustic oscillation feature. Other observations, such as the Hubble constant, the abundance of galaxy clusters, weak gravitational lensing and globular cluster ages, are generally consistent with these, providing a check of the model, but are less precisely measured at present.

Parameter values listed below are from the Planck Collaboration Cosmological parameters 68% confidence limits for the base ΛCDM model from Planck CMB power spectra, in combination with lensing reconstruction and external data (BAO + JLA + H0).[18] See also Planck (spacecraft).

- The "physical baryon density parameter" Ωb h2 is the "baryon density parameter" Ωb multiplied by the square of the reduced Hubble constant h = H0 / (100 km s−1 Mpc−1).[20][21] Likewise for the difference between "physical dark matter density parameter" and "dark matter density parameter".

- A density ρx = Ωxρcrit is expressed in terms of the critical density ρcrit, which is the total density of matter/energy needed for the universe to be spatially flat. Measurements indicate that the actual total density ρtot is very close if not equal to this value, see below.

- This is the minimal value allowed by solar and terrestrial neutrino oscillation experiments.

- from the Standard Model of particle physics

- Calculated from Ωbh2 and h = H0 / (100 km s−1 Mpc−1).

- Calculated from Ωch2 and h = H0 / (100 km s−1 Mpc−1).

- Calculated from h = H0 / (100 km s−1 Mpc−1) per ρcrit = 1.87847×10−26 h2 kg m−3.[12]

Missing baryon problem

Massimo Persic and Paolo Salucci[25] first estimated the baryonic density today present in ellipticals, spirals, groups and clusters of galaxies. They performed an integration of the baryonic mass-to-light ratio over luminosity (in the following ), weighted with the luminosity function over the previously mentioned classes of astrophysical objects:

The result was:

where .

Note that this value is much lower than the prediction of standard cosmic nucleosynthesis , so that stars and gas in galaxies and in galaxy groups and clusters account for less than 10% of the primordially synthesized baryons. This issue is known as the problem of the "missing baryons".

Extended models

| Description | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Total density parameter | 1.0023+0.0056 −0.0054 | |

| Equation of state of dark energy | −0.980±0.053 | |

| Tensor-to-scalar ratio | < 0.11, k0 = 0.002 Mpc−1 () | |

| Running of the spectral index | −0.022±0.020, k0 = 0.002 Mpc−1 | |

| Sum of three neutrino masses | < 0.58 eV/c2 () | |

| Physical neutrino density parameter | < 0.0062 |

Extended models allow one or more of the "fixed" parameters above to vary, in addition to the basic six; so these models join smoothly to the basic six-parameter model in the limit that the additional parameter(s) approach the default values. For example, possible extensions of the simplest ΛCDM model allow for spatial curvature ( may be different from 1); or quintessence rather than a cosmological constant where the equation of state of dark energy is allowed to differ from −1. Cosmic inflation predicts tensor fluctuations (gravitational waves). Their amplitude is parameterized by the tensor-to-scalar ratio (denoted ), which is determined by the unknown energy scale of inflation. Other modifications allow hot dark matter in the form of neutrinos more massive than the minimal value, or a running spectral index; the latter is generally not favoured by simple cosmic inflation models.

Allowing additional variable parameter(s) will generally increase the uncertainties in the standard six parameters quoted above, and may also shift the central values slightly. The Table below shows results for each of the possible "6+1" scenarios with one additional variable parameter; this indicates that, as of 2015, there is no convincing evidence that any additional parameter is different from its default value.

Some researchers have suggested that there is a running spectral index, but no statistically significant study has revealed one. Theoretical expectations suggest that the tensor-to-scalar ratio should be between 0 and 0.3, and the latest results are now within those limits.

See also

- Bolshoi Cosmological Simulation

- Galaxy formation and evolution

- Illustris project

- List of cosmological computation software

- Millennium Run

- Nature timeline

- Weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs)

- The ΛCDM model is also known as the standard model of cosmology, but is not related to the Standard Model of particle physics.

References

- Maeder, Andre (2017). "An Alternative to the ΛCDM Model: The Case of Scale Invariance". The Astrophysical Journal. 834 (2): 194. arXiv:1701.03964. Bibcode:2017ApJ...834..194M. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/834/2/194. ISSN 0004-637X.

- Brouer, Margot (2017). "First test of Verlinde's theory of emergent gravity using weak gravitational lensing measurements". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 466 (3): 2547–2559. arXiv:1612.03034. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.466.2547B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw3192.

- P. Kroupa, B. Famaey, K.S. de Boer, J. Dabringhausen, M. Pawlowski, C.M. Boily, H. Jerjen, D. Forbes, G. Hensler, M. Metz, "Local-Group tests of dark-matter concordance cosmology. Towards a new paradigm for structure formation" A&A 523, 32 (2010).

- Petit, J. P.; D’Agostini, G. (2018-07-01). "Constraints on Janus Cosmological model from recent observations of supernovae type Ia". Astrophysics and Space Science. 363 (7): 139. Bibcode:2018Ap&SS.363..139D. doi:10.1007/s10509-018-3365-3. ISSN 1572-946X.

- Pandey, Kanhaiya L.; Karwal, Tanvi; Das, Subinoy (2019-10-21). "Alleviating the H0 and S8 Anomalies With a Decaying Dark Matter Model". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. arXiv:1902.10636.

- Andrew Liddle. An Introduction to Modern Cosmology (2nd ed.). London: Wiley, 2003.

- Maeder, Andre; et al. (DES Collaboration) (2018). "First Cosmology Results using Type Ia Supernovae from the Dark Energy Survey: Constraints on Cosmological Parameters". The Astrophysical Journal. 872 (2): L30. arXiv:1811.02374. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab04fa.

- Maeder, Andre; et al. (Planck Collaboration) (2018). "Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters". arXiv:1807.06209 [astro-ph.CO].

- Tanabashi, M.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2019). "Astrophysical Constants and Parameters" (PDF). Physical Review D. Particle Data Group. 98 (3): 030001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.98.030001. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- Persic, Massimo; Salucci, Paolo (1992-09-01). "The baryon content of the Universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 258 (1): 14P–18P. arXiv:astro-ph/0502178. Bibcode:1992MNRAS.258P..14P. doi:10.1093/mnras/258.1.14P. ISSN 0035-8711.

- Dodelson, Scott (2008). Modern cosmology (4 ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0122191411.

- K.A. Olive; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2015). "The Review of Particle Physics. 2. Astrophysical constants and parameters" (PDF). Particle Data Group: Berkeley Lab. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Frieman, Joshua A.; Turner, Michael S.; Huterer, Dragan (2008). "Dark Energy and the Accelerating Universe". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 46 (1): 385–432. arXiv:0803.0982. Bibcode:2008ARA&A..46..385F. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.46.060407.145243.

- Kovac, J. M.; Leitch, E. M.; Pryke, C.; Carlstrom, J. E.; Halverson, N. W.; Holzapfel, W. L. (2002). "Detection of polarization in the cosmic microwave background using DASI". Nature. 420 (6917): 772–787. arXiv:astro-ph/0209478. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..772K. doi:10.1038/nature01269. PMID 12490941.

- Planck Collaboration (2016). "Planck 2015 Results. XIII. Cosmological Parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594 (13): A13. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830.

- Rini, Matteo (2017). "Synopsis: Tackling the Small-Scale Crisis". Physical Review D. 95 (12): 121302. arXiv:1703.10559. Bibcode:2017PhRvD..95l1302N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.95.121302.

- Merritt, David (2017). "Cosmology and convention". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics. 57: 41–52. arXiv:1703.02389. Bibcode:2017SHPMP..57...41M. doi:10.1016/j.shpsb.2016.12.002.

- Planck Collaboration (2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594 (13): A13. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830.

- Planck 2015,[18] p. 32, table 4, last column.

- Appendix A of the LSST Science Book Version 2.0 Archived 2013-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- p. 7 of Findings of the Joint Dark Energy Mission Figure of Merit Science Working Group

- Table 8 on p. 39 of Jarosik, N. et al. (WMAP Collaboration) (2011). "Seven-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Sky Maps, Systematic Errors, and Basic Results" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 192 (2): 14. arXiv:1001.4744. Bibcode:2011ApJS..192...14J. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/192/2/14. Retrieved 2010-12-04. (from NASA's WMAP Documents page)

- Planck Collaboration; Adam, R.; Aghanim, N.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A. J.; Barreiro, R. B. (2016-05-11). "Planck intermediate results. XLVII. Planck constraints on reionization history". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 596 (108): A108. arXiv:1605.03507. Bibcode:2016A&A...596A.108P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201628897.

- Spergel, D. N. (2015). "The dark side of the cosmology: dark matter and dark energy". Science. 347 (6226): 1100–1102. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1100S. doi:10.1126/science.aaa0980. PMID 25745164.

- The baryon content of the universe, M. Persic and P. Salucci, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 1992

Further reading

- Rebolo, R.; et al. (2004). "Cosmological parameter estimation using Very Small Array data out to ℓ= 1500". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 353 (3): 747–759. arXiv:astro-ph/0402466. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.353..747R. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08102.x.

- Ostriker, J. P.; Steinhardt, P. J. (1995). "Cosmic Concordance". arXiv:astro-ph/9505066.

- Ostriker, Jeremiah P.; Mitton, Simon (2013). Heart of Darkness: Unraveling the mysteries of the invisible universe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13430-7.