Strikebreaker

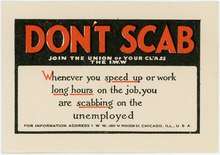

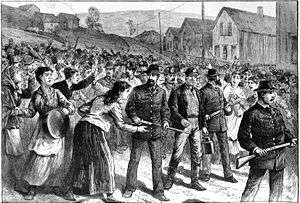

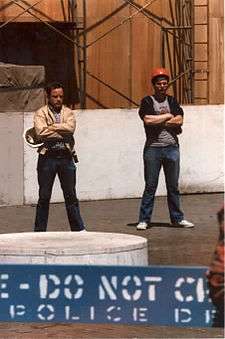

A strikebreaker (sometimes derogatorily called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company prior to the trade union dispute, but rather hired after or during the strike to keep the organization running. "Strikebreakers" may also refer to workers (union members or not) who cross picket lines to work.

The use of strikebreakers is a worldwide phenomenon; however, many countries have passed laws outlawing their use, as they undermine the collective bargaining process. Strikebreakers are used far more frequently in the United States than in any other industrialized country.[1]

International law

| Look up strikebreaker in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The right to strike is not expressly mentioned in any convention of the International Labour Organization (ILO);[2] however, the ILO's Freedom of Association Committee established principles on the right to strike through ongoing rulings.[3] Among human rights treaties, only the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights contains a clause protecting the right to strike. However, like the Social Charter of 1961, the Covenant permits each signatory country to abridge the right to strike.[4]

The ILO Committee on Freedom of Association and other ILO bodies have, however, interpreted all core ILO conventions as protecting the right to strike as an essential element of the freedom of association. For example, the ILO has ruled that "the right to strike is an intrinsic corollary of the right of association protected by Convention No. 87."[5]

The ILO has also concluded striker replacement, while not in contravention of ILO agreements, carries with it significant risks for abuse and places trade union freedoms "in grave jeopardy."[5][6]

The European Social Charter of 1961 was the first international agreement to expressly protect the right to strike.[2] However, the European Union's Community Charter of the Fundamental Social Rights of Workers permits EU member states to regulate the right to strike.[7]

National laws

Asia

- Japanese labor law significantly restricts the ability of both an employer and a union to engage in labor disputes. The law highly regulates labor relations to ensure labor peace and channel conflict into collective bargaining, mediation and arbitration. It bans the use of strikebreakers.[8]

- South Korea bans the use of strikebreakers, although the practice remains common.[9]

Europe

In most European countries, strikebreakers are rarely used. Consequently, they are rarely if ever mentioned in most European national labor laws.[2] As mentioned above, it is left to the European Union member states to determine their own policies.[7]

- Germany has employment law that strongly protects worker rights, but trade unions and the right to strike are not regulated by statute. The Bundesarbeitsgericht (the Federal Labor Court of Germany) and the Bundesverfassungsgericht (the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany) have, however, issued a large number of rulings which essentially regulate trade union activities such as strikes. Work councils, for example, may not strike at all, but trade unions retain an almost unlimited ability to strike. The widespread use of work councils, however, channels most labor disputes and reduces the likelihood of strikes. Recent efforts to enact a comprehensive federal labor relations law that regulates strikes, lockouts and the use of strikebreakers failed.[10]

- United Kingdom laws permit strikebreaking, and courts have significantly restricted the right of unions to punish members who act as strikebreakers.[11]

North America

- Canada has federal industrial relations laws that strongly regulate the use of strikebreakers. Although many Canadian labor unions today advocate for even stronger regulations, scholars point out that Canadian labor law has far greater protections for union members and the right to strike than American labor law, which has significantly influenced the development of labor relations in Canada.[12] In Quebec, the use of strikebreakers is illegal,[13] but companies may try to remain open with only managerial personnel.[2]

- Mexico has a federal labor law that requires companies to cease operations during a legal strike, effectively preventing the use of strikebreakers.[2]

- The U.S. Supreme Court held in NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co., 304 U.S. 333 (1938) that an employer may not discriminate on the basis of union activity in reinstating employees at the end of a strike. The ruling effectively encourages employers to hire strikebreakers so that the union loses majority support in the workplace when the strike ends.[14] The Mackay Court also held that employers enjoy the unrestricted right to permanently replace strikers with strikebreakers.[15]

Synonyms

Strikebreaking is also known as "black-legging" or "blacklegging". American lexicographer Stephanie Smith suggests that the word has to do with bootblacking or shoe polish, for an early occurrence of the word was in conjunction with an 1803 American bootmaker's strike.[16] But British industrial relations expert J.G. Riddall notes that it may have a racist connotation, as it was used in this way in 1859 in the United Kingdom: "If you dare work we shall consider you as blacks..."[17] Lexicographer Geoffrey Hughes, however, notes that "blackleg" and "scab" are both references to disease, as in the blackleg infectious bacterial disease of sheep and cattle caused by Clostridium chauvoei. He dates the first use of the term "blackleg" in reference to strikebreaking to the United Kingdom in 1859. The use of the term blackleg for a strikebreaker was, however, previously recorded in 1832 during the trial of special constable George Weddell for killing and slaying Cuthbert Skipsey, a striking pitman, near Chirton, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.[18] Hughes observes that the term was once generally used to indicate a scoundrel, a villain, or a disreputable person.[19] However, the Northumbrian folk song Blackleg Miner is believed to originate from the 1844 strike, which would predate Hughes's reference.[20] David John Douglass claims that the term blackleg has its origins in coal mining, as strikebreakers would often neglect to wash their legs, which would give away that they had been working whilst others had been on strike.[21]

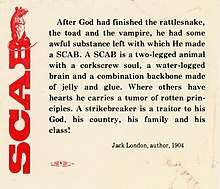

Hughes notes that the use of the term "scab" can be traced back to the Elizabethan era in England, and is much more clearly rooted in the concept of disease (e.g., a diseased person) and a sickened appearance.[19] The word is occasionally still used as a general insult in Britain; for example, during a mock funeral for Margaret Thatcher in 2013 in Goldthorpe, the word "scab" was spelled out in flowers as part of the display.[22] A traditional English proverb, which advises against gossip, is He that is a blab is a scab.[23]

John McIlroy has suggested that there is a distinction between a blackleg and a scab. He defines a scab as an outsider who is recruited to replace a striking worker, whereas a blackleg is one already employed who goes against a democratic decision of their colleagues to strike, and instead continues to work.[24] The fact that McIlroy specified that this should be a "democratic" decision has led the historian David Amos to question whether the Nottinghamshire miners in 1984–85 were true blacklegs, given the lack of a democratic vote on the strike.[25]

Strikebreakers are also known as "knobsticks". The term appears derived from the word "knob", in the sense of something that sticks out, and from the card-playing term "nob", as someone who cheats.[26]

See also

- Molly Maguires

- "The Scab" by Jack London (attributed)

- "Blackleg Miner" (song)

- Mohawk Valley formula

- Percy the Small Engine

Notes

- Norwood, Strikebreaking and Intimidation, 2002.

- Human Rights Watch, Unfair Advantage: Workers' Freedom of Association in the United States Under International Human Rights Standards, 2000.

- ILO principles concerning the right to strike 2000 ISBN 92-2-111627-1

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Article 8 (4).

- International Labour Organization, Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining: General Survey of the Reports... 1994.

- Committee on Freedom of Association, Digest of Decisions of the Committee on Freedom of Association, 2006.

- Maastricht Treaty on European Union, Protocol and Agreement on Social Policy, February 7, 1992, 31 LL.M. 247, paragraph 13 under "Freedom of association and collective bargaining."

- Sugeno and Kanowitz, Japanese Employment and Labor Law, 2002; Dau-Schmidt, "Labor Law and Industrial Peace: A Comparative Analysis of the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan Under the Bargaining Model," Tulane Journal of International & Comparative Law, 2000.

- Parry, "Labour Law Draws Roar of Rage From Asian Tiger," The Independent, January 18, 1997.

- Körner, "German Labor Law in Transition," German Law Journal, April 2005; Westfall and Thusing, "Strikes and Lockouts in Germany and Under Federal Legislation in the United States: A Comparative Analysis," Boston College International & Comparative Law Review, 1999.

- Ewing, "Laws Against Strikes Revisited," in Future of Labour Law, 2004.

- Logan, "How 'Anti-Union' Laws Saved Canadian Labour: Certification and Striker Replacements in Post-War Industrial Relations," Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, January 2002.

- Quebec Labour Code Section 109.1

- Getman and Kohler, "The Story of NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co.," in Labor Law Stories, 2005, pp. 49-50.

- Getman and Kohler, "The Story of NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co.," in Labor Law Stories, 2005, p. 13.

- Smith, Household Words: Bloomers, Sucker, Bombshell, Scab, Nigger, Cyber, p. 98.

- Riddall, p. 209.

- Tyne Mercury, 10 July 1832

- Hughes, p. 466.

- Amos, David (December 2011). "THE NOTTINGHAMSHIRE MINERS', THE UNION OF DEMOCRATIC MINEWORKERS AND THE 1984-85 MINERS STRIKE: SCABS OR SCAPEGOATS?" (PDF). University of Nottingham. p. 289. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

The song, Blackleg Miner, is thought to originate from the 1844 Miners' Lockout in the North East Coalfield.

- Douglass, David John (2005). Strike, not the end of the story. Overton, Yorkshire, UK: National Coal Mining Museum for England. p. 2.

- Goldthorpe hosts anti-Margaret Thatcher funeral

- Apperson, George Latimer; Manser, Martin H (2007). Dictionary of Proverbs. Wordsworth Editions. p. 57. ISBN 9781840223118.

- McIlroy, John, Strike: How to fight and how to win, page 150 (London, 1984), quoted in Amos, David (December 2011). "THE NOTTINGHAMSHIRE MINERS', THE UNION OF DEMOCRATIC MINEWORKERS AND THE 1984-85 MINERS STRIKE: SCABS OR SCAPEGOATS?" (PDF). University of Nottingham. pp. 293–4. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- Amos, David (December 2011). "THE NOTTINGHAMSHIRE MINERS', THE UNION OF DEMOCRATIC MINEWORKERS AND THE 1984-85 MINERS STRIKE: SCABS OR SCAPEGOATS?" (PDF). University of Nottingham. p. 294. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

If we use McIlroy's interpretation can the Nottinghamshire miners of 1984-85 be seen to have been 'blacklegging' as against 'scabbing'? However, there is one contentious point in McIlroy's interpretation, the breaking of the 'democratic process'. It is because there was some debate over the democratic process in the 1984-85 miners' strike that the question is raised as to whether the working Nottinghamshire miners were scabs at all.

- Schillinger 2012, pp. 104, 120.

References

- Committee on Freedom of Association. International Labour Organization. Digest of Decisions of the Committee on Freedom of Association. 5th (revised) ed. Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2006.

- Dau-Schmidt, Kenneth Glenn. "Labor Law and Industrial Peace: A Comparative Analysis of the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan Under the Bargaining Model." Tulane Journal of International & Comparative Law. 2000.

- Ewing, Keith. "Laws Against Strikes Revisited." In Future of Labour Law. Catharine Barnard, Gillian S. Morris, and Simon Deakin, eds. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2004. ISBN 9781841134048

- Getman, Julius G. and Kohler, Thomas C. "The Story of NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co.: The High Cost of Solidarity." In Labor Law Stories. Laura J. Cooper and Catherine L. Fisk, eds. New York: Foundation Press, 2005. ISBN 1587788756

- Hughes, Geoffrey. An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-Speaking World. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 2006.

- Human Rights Watch. Unfair Advantage: Workers' Freedom of Association in the United States Under International Human Rights Standards. Washington, D.C.: Human Rights Watch, 2000. ISBN 1564322513

- International Labour Organization. Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining: General Survey of the Reports on the Freedom of Association and the Right to Organise Convention (No. 87), 1948, and the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention (no. 98), 1949. Geneva: International Labour Organization, 1994.

- Körner, Marita. "German Labor Law in Transition." German Law Journal. 6:4 (April 2005).

- Logan, John. "How 'Anti-Union' Laws Saved Canadian Labour: Certification and Striker Replacements in Post-War Industrial Relations." Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations. 57:1 (January 2002).

- Norwood, Stephen H. Strikebreaking and Intimidation. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 0807827053

- Parry, Richard Lloyd. "Labour Law Draws Roar of Rage From Asian Tiger." The Independent. January 18, 1997.

- Riddall, J.G. The Law of Industrial Relations. London: Butterworths, 1982.

- Schillinger, Stephen (2012). "Begging at the Gate: Jack Straw and the Acting Out of Popular Rebellion". In Cerasano, S.P. (ed.). Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England. Vol. 21. Madison, Wisc.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9780838643976.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silver, Beverly J. Forces of Labor: Workers' Movements and Globalization Since 1870. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0521520770

- Smith, Robert Michael. From Blackjacks to Briefcases: A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2003. ISBN 0821414658

- Smith, Stephanie. Household Words: Bloomers, Sucker, Bombshell, Scab, Nigger, Cyber. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. ISBN 0816645531

- Sugeno, Kazuo and Kanowitz, Leo. Japanese Employment and Labor Law. Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press, 2002. ISBN 0890896119

- Westfall, David and Thusing, Gregor. "Strikes and Lockouts in Germany and Under Federal Legislation in the United States: A Comparative Analysis." Boston College International & Comparative Law Review. 22 (1999).