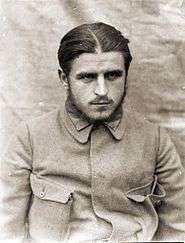

Stefan Starzyński

Stefan Bronisław Starzyński (August 19, 1893, Warsaw[1] – between December 21 and 23, 1939[2]) was a Polish statesman, economist, military officer and Mayor of Warsaw before and during the Siege of 1939.

Stefan Starzyński | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mayor of Warsaw | |

| In office 2 August 1934 – 27 October 1939 | |

| Preceded by | Marian Zyndram-Kościałkowski |

| Succeeded by | Julian Kulski |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 19, 1893 Warsaw, Poland (then Russian Empire) |

| Died | between December 21 and 23, 1939 Warsaw or surroundings, Occupied Poland |

| Signature | |

Early life, studies and career

Stefan Bronisław Starzyński was born on August 19, 1893 in Warsaw. He participated in the 1905 school strike. After graduating from a gymnasium, he enrolled in the Department of Economics at the Higher School of Trade (Wyższe Kursy Handlowe), a private-run university, now Warsaw School of Economics. In 1909 he also joined various patriotic organizations, including the Riflemen's Association (Związek Strzelecki).

In August 1914, after the outbreak of the Great War, he joined Piłsudski's Polish Legions and became an ordinary soldier in the 1st Brigade. He took part in all battles and skirmishes of his Brigade and was quickly promoted to officer. After the Pledge Crisis in 1917 he was arrested and, together with most of his colleagues, interned in Beniaminów. In November 1918 he joined the Polish Army and became the Chief of Staff of the 9th Polish Infantry Division. During the Polish-Bolshevik War he was transferred to the 2nd Department of the General Staff, which carried out mostly intelligence tasks.

After demobilization he remained in public service. He supervised one of the repatriation commissions in Moscow and later one of the departments of the Ministry of Treasury. In the years 1929–30 and 1931–32 he was a deputy minister of the treasury. In 1930 he became a member of Polish Sejm for a three years period as a member of the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR). He was also a deputy president of Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego, one of the largest Polish banks.

During his life he published several academic papers on the economy.

Mayor of Warsaw

In the early 1930s Warsaw had a huge hole in its budget. The city's development had been halted by a lack of funds while the population continued to grow rapidly. On August 1, 1934, Starzyński was chosen by the Sanacja régime to become the president of Warsaw, and was given special powers. Local authorities were disbanded and Starzyński became responsible only to central government.

At first Starzyński was viewed by the majority of Varsovians as yet another Sanacja stooge imposed on a city that mostly supported the opposition. But he soon gained popularity, even among his former enemies. He initiated a plan for fast-track reform of the financial system. The money saved thanks to these reforms was reinvested in public works that reduced unemployment. He managed to electrify the suburbs of Wola and Grochów, pave all the major roads out of Warsaw, and to connect the city centre with the newly built northern district of Żoliborz through a bridge over the northern railway line. These actions earned him the nickname "president of the suburbs".

He became popular among the inhabitants of the borough of Śródmieście (city centre) for his action of planting trees and flowers along the main streets. Starzyński also ordered the creation of a huge park in Wola and several minor green areas in other parts of the city. During his presidency Warsaw was also enlarged to the south. The area of former airfield on Pole Mokotowskie in the borough of Mokotów was cut in two parts by Aleje Niepodległości (Avenue of Independence), nowadays one of the main streets of Warsaw. Among the most important facilities opened during his presidency were the National Museum, new building of the city library, new building of his alma mater, now renamed to Warsaw School of Economics and the Powszechny theatre, which became one of the most influential scenes of Warsaw. Other initiatives of Starzyński include complete reconstruction of boulevards along the Vistula and partial reconstruction of the barbican in the Old Town area.

In 1934 he was chosen as a president of Warsaw for a four-year term. On December 18, 1938 he was elected in democratic elections for his second term. Starzyński held his office until World War II broke out. During his presidency:

- 2,000,000 km² of paved roads were built

- 44 schools were opened

- National Museum was built

- 2 major parks were opened to the public (one of them is now a National Reserve)

- construction of Warsaw Metro started

World War II

After the start of Polish Defensive War of 1939 Starzyński, refused to leave Warsaw together with other state authorities and diplomats on September 4, 1939. Instead he joined the army as a major of infantry. The Minister of War shortly before his departure created the Command of the Defense of the Capital with general Walerian Czuma as its commander. On September 7, the forces of 4th German Panzer Division managed to break the Polish lines near Częstochowa and started their march towards Warsaw. Most of the city authorities were evacuated to the east. Warsaw was left with a military garrison composed mainly of infantry battalions and batteries of artillery. The Headquarters of general Czuma had to organize the defense of the city. Unfortunately, there was some misunderstanding among the command. At that time Poland still believed that any time soon Great Britain and France would attack Germany according to the treaties which were signed by these countries at the beginning of 1939. As it happened these obligations were never to materialise. However, at that stage the Polish authorities wanted to preserve younger reservists for future fighting, so the spokesman of the garrison of Warsaw issued a communique in which he ordered all young men to leave the city. That step weakened the strength of the defence garrison.

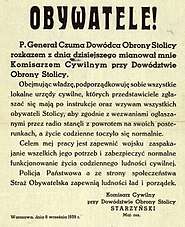

To counter the mess that started in Warsaw, general Czuma appointed Stefan Starzyński as the Civilian Commissar of Warsaw. Starzyński started to organize the Civil Guard to replace the evacuated police forces. He also ordered all members of the city's administration to retake their posts. In his daily radio releases he asked all civilians to construct barricades and anti-tank barriers at the outskirts of Warsaw. According to many sources from the epoch his daily speeches were a crucial factor in keeping the morale of both the soldiers and the civilians high during the Siege of Warsaw. Starzyński commanded the distribution of food, water and supplies as well as fire fighting brigades. He also managed to organise shelter for almost all civilian refugees from other parts of Poland and houses destroyed by German aerial bombardment. Before the Siege ended he became the symbol of the defence of Warsaw in 1939.

On September 27 the commanders of the besieging German forces demanded that Starzyński be present during the signing of the capitulation of Warsaw. Before the capitulation he was offered to leave the city several times. The pilot of the prototype PZL.46 Sum plane that managed to escape from internment in Romania and landed safely in besieged Warsaw offered himself to evacuate Starzyński to Lithuania. He was also proposed to go underground and receive plastic surgery in order to escape the city. He refused.

After the Germans entered the city on September 28, 1939, Starzyński was allowed to continue his service as the president of Warsaw. He was active in organisation of life in the occupied city as well as its reconstruction after the German terror bombing campaign. At the same time he became one of the organizers of Służba Zwycięstwu Polski, the first underground organisation in occupied Poland that eventually became the Armia Krajowa. Among other things he provided it with thousands of clean forms of ID cards, birth registry forms and passports. Those documents were later used in validation of false identities of many members of the resistance.

Arrest and death

On October 5, he was arrested by the Gestapo and, together with several other prominent inhabitants of Warsaw, held hostage as a warrant of safety for Adolf Hitler during a parade of victory held in Warsaw. The following day all of them were released. On October 27, 1939 he was again arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned in the Pawiak prison. In December he was yet again offered to escape, but he again refused claiming that it would be too costly to those involved in his escape.

His fate remained unknown until, on September 8, 2014, the Polish IPN-Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej) officially closed the investigation of the circumstances of his death. Based on a recent eyewitness testimony,[3] the IPN's commission of inquiry came to the conclusion that Stefan Starzyński was shot by the Gestapo at some point between December 21 and 23, 1939. in Warsaw or its surroundings. The crime was committed by Gestapo functionaries Oberscharführer Hermann Schimmann, Hauptscharführer Weber, and Unterscharführer Perlbach. However, it has not been possible to unambiguously establish the Gestapo functionaries who had given the order to kill Stefan Starzyński.[4]

According to an earlier version of the account, which has been discarded by the IPN, it was believed that Starzyński had been transferred to Moabit prison in Berlin and then to Dachau concentration camp, where he was thought to have died. Several other accounts had assumed that he was either transferred to a potash mine in Baelberge or that he was held hostage in Warsaw until the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising. The date of his death was assumed to be October 17, 1943 (shot to death in the Dachau concentration camp), although other versions mentioned August 1944 (Warsaw), 1944 (Baelberge), 1943 (Spandau prison) or January 1940 (Dachau).

One version of the account was based on documents, which the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) had received from Germany in 2008. The documents had been held in the archives of former East German Ministry of State Security ("Stasi"), and they claimed that Starzyński was tortured and died on March 19, 1944 in a potassium salt mine, where he was allegedly held captive at a prisoner of subsidiaries camp and slave-worked in Leipzig Enterprise Transport, which produced aircraft parts. According to witnesses, he was allegedly placed on the board set on trestles, holding 2 full buckets of water, under the "penalty" of being shot if he would drop them. According to this account, Starzyński stood on it until he collapsed and died of exhaustion.[5] This version of the circumstances of Starzyński's death was also discarded by the IPN in September 2014.[6]

In 1957, a memorial was erected to his memory in the Powązki cemetery in Warsaw.

Legacy and remembrance

After the war the rebuilt Warszawa II radio station was named after him. Currently there are several monuments to Starzyński in Warsaw as well as a street and several schools named after him. His September 1939 radio broadcasts are now considered to be a part of popular culture in Poland. Starzyński's silent, hoarsened voice and the texts of his speeches are nowadays easily recognizable by most Varsovians. In 2003 the readers of news papers and the spectators of the Warsaw branch of the public television elected Starzyński as the Varsovian of the Century by a huge majority of votes.

In 1978 his popularized story was filmed by Andrzej Trzos-Rastawiecki in his movie Gdziekolwiek jesteś, panie prezydencie (Wherever You Are, Mr. President).

See also

- Warsaw

- President of Warsaw

- Polish Defensive War of 1939

- Siege of Warsaw (1939)

- Prometheism

Notes and references

General

- "IPN chce się dowiedzieć, jak zginał Stefan Starzyński" (in Polish). Życie Warszawy.

- "Investigation of Warsaw President Stefan Starzyński's Death Has Been Closed" (in Polish). IPN. September 2014. Archived from the original on September 15, 2014.

- "The Man who Governed Warsaw After Starzynki's Arrest" (in Polish). Gazeta Wyborcza. September 2014.

- "Investigation of Warsaw President Stefan Starzyński's Death Has Been Closed" (in Polish). IPN. September 2014. Archived from the original on September 15, 2014.

- "Investigation of Stefan Starzyński's death continues at IPN" (in Polish). Życie Warszawy. March 9, 2008.

- "IPN Determined Circumstances of Starzynski's Death" (in Polish). Polskie Radio. September 2014.

- Norbert Konwinski (1978). The Mayor: Saga of Stefan Starzynski. Claremont: Diversified Enterprises. ISBN 0-9601790-0-3.

- Marian Marek Drozdowski (1980). Stefan Starzyński, prezydent Warszawy (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. p. 394. ISBN 83-06-00265-2.

- various authors (1982). Marian Marek Drozdowski (ed.). Wspomnienia o Stefanie Starzyńskim (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 427. ISBN 83-01-02785-1.

- Julian Kulski (1990). Stefan Starzyński w mojej pamięci (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 133. ISBN 83-01-10180-6.

- Stefan Starzyński (1994). Marian Marek Drozdowski; Juliusz Ludwik Englert; Hanna Szwankowska (eds.). Chciałem by Warszawa była wielka (in Polish). Warsaw: Obywatelski Komitet Budowy Pomnika Stefana Starzyńskiego, Omnia. p. 160. ISBN 83-85252-56-8.

- Anna Kardaszewicz; Towarzystwo im. Stanisława ze Skarbimierza (corporate author) (2000). Stefan Starzyński (in Polish). Warsaw: DiG. p. 100. ISBN 83-7181-109-8.

- Stefan Starzyński; Marian Marek Drozdowski, Lech Kaczyński (2004). Marian Marek Drozdowski (ed.). Archiwum Prezydenta Warszawy Stefana Starzyńskiego (in Polish). p. 394. ISBN 83-7399-075-5.

External links

- Arrest of President Stefan Starzyński – 27.X.1939 (Polish)

- Investigation of Warsaw President Stefan Starzyński's Death Has Been Closed (Polish) IPN-Institute of National Remembrance

- IPN Determined Circumstances of Starzynski's Death (Polish) Polskie Radio

- The Man who Governed Warsaw After Starzynki's Arrest(Polish) Gazeta Wyborcza

- IPN investigates German murder of Stefan Starzyński (Polish) IPN-Institute of National Remembrance

- Stefan Conrad Starzyński (Polish)

- Warsaw 1939 – historical guide (Polish)

- Spy in London (Polish)