Staszów

Staszów[2][3][4] [ˈstaʂuf] is a town in Poland, in Świętokrzyskie Voivodship (historic province of Lesser Poland), about 54 kilometres (34 miles) southeast of Kielce, and 120 km (75 mi) northeast of Kraków. It is the capital of Staszów County. The population is 15,108 (2010), which makes it the 8th largest urban center of the province. The area of the town is 26,88 km2, and its two rivers are the Desta and the Czarna Staszowska.

Staszów | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Old Town Hall and Market Square | |

Coat of arms | |

Staszów | |

| Coordinates: 50°33′48″N 21°10′18″E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Świętokrzyskie |

| County | Staszów County |

| Gmina | Gmina Staszów |

| Town rights | 11 April 1525 |

| Parts of town | Townships' List

|

| Area (through the years 2007-2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 26.88 km2 (10.38 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 199 m (653 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2013 at Census)[1] | |

| • Total | 15,517 |

| • Density | 580/km2 (1,500/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 28-200 |

| Area code(s) | +48 15 |

| Car plates | TSZ |

| Website | http://www.staszow.pl |

Staszów's coat of arms is the Korab, ancient symbol of several noble families of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Moreover, Hieronymus Jaroslaw Łaski of Korab coat of arms, founded the town. Staszów remained in private hands until October 1866. It has a rail station, near the town also goes the Broad Gauge Metallurgy Line.

The name of the town comes from given name Stanisław, which in the 13th and 14th centuries was used in diminutive form Stasz. It is probable that the first owner of the town was a man named Stasz Kmiotko. Staszów is home to a sports club Pogoń, founded in 1945.

Location

Staszów is located in southeastern corner of Świętokrzyskie Mountains, in historic Sandomierz Land, which in 1314 turned into Lesser Poland’s Sandomierz Voivodeship. The town remained within borders of this voivodeship for hundreds of years, until 1795 (see Partitions of Poland). Between 1796–1809 it belonged to Austrian Empire, and then to Duchy of Warsaw, which after the Congress of Vienna became Congress Poland, a Russian protectorate. In 1844 Staszów County, which had been created in 1809, was disbanded, and its territory merged with Sandomierz County.

In the Second Polish Republic Staszów belonged to Sandomierz County of Kielce Voivodeship, and during World War II, it was part of Radom District of the General Government. After the war, Kielce Voivodeship was re-created, and in 1954, Staszów County returned. Between 1975 and 1998, the town belonged to Tarnobrzeg Voivodeship. Staszów is surrounded by forests, which make 36% of the county. The town is located between the colder climate of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, and the milder temperatures of the Sandomierz Valley. Winters are cold, summers hot, and autumns warm and long. Average January temperature is −3 °C (27 °F), July 17–18,3 °C (37 °F), while average annual temperature is 7 to 8 °C (45 to 46 °F).

History

First mention of the town comes from 1241, when, during Mongol invasion of Europe, the village of Staszów was burned, together with its wooden parish church. In 1345, new stone church of St. Bartholomew was built, and in the 1440s, the village of Staszów was mentioned in Jan Długosz’s Liber Beneficiorum Dioecesis Cracoviensis. In the early 16th century, Staszów had a market square with a town hall, surrounded by tenement houses. The first Jews settled in Staszów around the time it was awarded city status, in 1526, and a shortly after an organized Jewish community was established there.[5][6] In 1580 it emerged as one of centers of Protestant Reformation in Lesser Poland, with Polish Brethren active here. The town belonged to several noble families, including the Opaliński and the Tęczyński. In 1610 The Jewish inhabitants were accused of a blood libel of ritual murder. A trial took place, after which they were expelled from the city. Even after the deportation, several Jews remained, who also suffered from blood libels.[5][6]

The ban on Jews living in Staszow was officially abolished only 80 years after the expulsion of the Jews, in 1690. Then the number of Jews grew quickly and the Jewish community resumed its presence.[5] In 1709, a few years after an outbreak of black death, Staszów was captured and destroyed by the Swedes (see: Great Northern War). On May 2, 1718, Staszów’s-then owner, Elżbieta Sieniawska, played an important role in the development of the Jewish community in Staszow, when she granted them a privlige that included a permit to build a synagogue and cemetery.[5][6] In 1731, Staszów belonged to the Czartoryski family, and soon afterwards, August Czartoryski completed the construction of a new town hall with a clock tower. In 1795 Staszów was annexed by Austria to the province of West Galicia, then, during Napoleonic Wars, was part of Duchy of Warsaw, later Russian-controlled Congress Poland. In 1815 for the first time ever Staszów became a seat of the county. Its inhabitants participated in both November Uprising and January Uprising, so Russian government decided that a Russian Imperial Army garrison of 800 was stationed there. By 1900, Staszów emerged as a local trade center, with a brewery, several mills, and other enterprises.

During World War I, Staszów was the area of heavy fighting between the Russians and the Austro-Hungarians. The town changed hands several times, and in November 1918 it was free. Soon afterwards, it became part of Sandomierz County of Kielce Voivodeship, and by 1930, its population was 10,000, half of which was Jewish.

In World War II, Staszów was an important center of anti-German resistance, where the Jędrusie and the Home Army units were active.

The Germans occupied Staszów in September 1939 and immediately began to rob and brutalize the Jewish population which then comprised about half of Staszów's 11,000 inhabitants. Jews from other towns, including from Austria, were brought to Staszów. Both those Jews and local Jews were obligated to perform forced labor for the Germans, building roads and draining swamps, among other tasks. The influx of people brought about epidemic diseases, including both typhus and typhoid. Beginning in January 1942, Jews were forbidden to leave the town. A two part ghetto with more than 6000 inhabitants was established in June 1942 and more Jews were brought there from around the region.

News had spread about deportations to killing camps of other Jewish communities. Many Jews fled Staszów and others tried to hide with Polish neighbors or in the forest. Attempts were made to develop an armed resistance, but Polish resistance forces would not arm Jews. In the evening of November 7, the town was surrounded by Germans, Ukrainian and Latvian auxiliaries, and Polish and Jewish police. The next day, around 6000 Jews were marched to the train station. Hundreds were killed en route and others were beaten. The train took the rest to Treblinka where they were murdered. [7] This day is called "Black Sunday" by members of Staszów's Jewish community.

After that, a search of Jewish houses began and those who were hiding were shot. Some hiding places were revealed by Polish townspeople. A few Poles hid Jews from the occupiers, including Maria Szczecinka, a widow who hid fourteen until liberation. Some Jews managed to escape in many ways into the Golieb forest outside of Staszów. These Jews became Partisans and established camps, bunkers and raided Nazi supplies until the end of the war. The number of Staszów's Jewish survivors is unknown.

Black Sunday

Obersturmfuehrer Schild ordered the Jewish policemen to instruct all the Jews in town to be present by 8 o'clock in the morning at the marketplace. Anybody who did not obey this order would be shot.[8] By 8 o'clock in the morning about 5,000 Jews, young and old, children and grown-ups, had assembled at the market place in order to begin their march to death. At 10 in the morning, Schild gave the order: “March! And so the people started the march and as soon as they filed into Krakowska Street, the murderers shot into the mass of people, strewing the whole road with innocent victims. Blood ran from the Krakowska street down to the river. The march of the Staszów Jews took them through Szczucin and Stopnica to Belzec extermination camp. More than 1,000 Jews reached Stopnica. In Niziny village, 9 km (6 mi) from Staszów, a mass grave was dug for 740 victims.

Those who had not come at 8 AM to the marketplace were bestially murdered in their homes. All those killed in Staszów itself on the day of slaughter were buried in a single mass grave at the Jewish Cemetery. Many more Jews, who were retained for hard labor or who had hidden in bunkers, were subsequently killed or shipped to a concentration camp.

The Germans retreated in January 1945, after the hostilities and aerial bombardment of the town, 80% of it was destroyed.

Points of interest

Staszów managed to keep its medieval shape, with a market square, a town hall in the middle, and perpendicular streets. The town was frequently destroyed and burned, its most notable historic building is St. Bartholomew church, built in 1342 - 1343, in the spot where a wooden church had stood, burned by the Tatars in 1241. The church was renovated several times, and its present shape differs from the original. There are 18th and 19th century tenement houses in the market square, and the town hall was built in 1783, with major changes from 1861.

Jewish Cemetery

Over 175 years old, the Jewish Cemetery was not maintained, and at one point was even replaced without a trace by a playground. The newer Jewish cemetery, 1 km (0.6 mi) from the center of Staszow, was an empty lot. The gravestones had been carted away by the Nazis for use as paving stones on muddy roads and sold to a construction company by municipal authorities after the war when no Jews returned to claim them. An individual, Jack Goldfarb,[9] living in New York City paid to have the grounds spruced up, to have a 3 m (10-foot) Holocaust memorial constructed, to have some 155 Jewish gravestones he discovered in Staszow homes brought back to the cemetery, and to have a marker set up at a Holocaust-era mass grave.

Demography

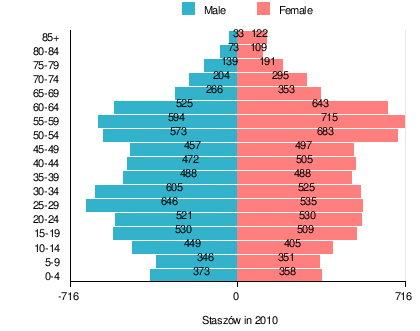

According to the 2011 Poland census, there were 15,108 people residing in Staszów town, of whom 48.3% were male and 51.7% were female. In the town, the population was spread out with 19% under the age of 18, 38.2% from 18 to 44, 26.8% from 45 to 64, and 16.1% who were 65 years of age or older.[1]

Table 1. Population level of town in 2010 — by age group[1] SPECIFICATION Measure

unitPOPULATION

(by age group in 2010)TOTAL 0-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85 + I. TOTAL person 15,108 731 697 854 1,039 1,051 1,181 1,130 976 977 954 1,256 1,309 1,168 619 499 330 182 155 — of which in % 100 4.8 4.6 5.7 6.9 7 7.8 7.5 6.5 6.5 6.3 8.3 8.7 7.7 4.1 3.3 2.2 1.2 1 1. BY SEX A. Males person 7,294 373 346 449 530 521 646 605 488 472 457 573 594 525 266 204 139 73 33 — of which in % 48.3 2.5 2.3 3 3.5 3.4 4.3 4 3.2 3.1 3 3.8 3.9 3.5 1.8 1.4 0.9 0.5 0.2 B. Females person 7,814 358 351 405 509 530 535 525 488 505 497 683 715 643 353 295 191 109 122 — of which in % 51.7 2.4 2.3 2.7 3.4 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.2 3.3 3.3 4.5 4.7 4.3 2.3 2 1.3 0.7 0.8

Figure 1. Population pyramid of town in 2010 — by age group and sex[1]

Table 2. Population level of town in 2010 — by sex[1] SPECIFICATION Measure

unitPOPULATION

(by sex in 2010)TOTAL Males Females I. TOTAL person 15,108 7,294 7,814 — of which in % 100 48.3 51.7 1. BY AGE GROUP A. At pre-working age person 2,868 1,490 1,378 — of which in % 19 9.9 9.1 B. At working age. grand total person 9,812 5,089 4,723 — of which in % 65 33.7 31.3 a. at mobile working age person 5,768 2,940 2,828 — of which in % 38.2 19.5 18.7 b. at non-mobile working age person 4,044 2,149 1,895 — of which in % 26.8 14.2 12.5 C. At post-working age person 2,428 715 1,713 — of which in % 16.1 4.7 11.4

Districts

City consists of 10 districts:

- Osiedle Oględowska - Złodziejówka (Thief Village)

- Osiedle Ogrody (The Gardens)

- Osiedle Północ (North town)

- Osiedle Wschód - Pipała (East town)

- Stare Miasto (Old town alias Downtown)

- Staszówek

- Golejów

- Radzików

- Pocieszka

- Małopolskie

References

- "Local Data Bank (Bank Danych Lokalnych) – Layout by NTS nomenclature (Układ wg klasyfikacji NTS)". demografia.stat.gov.pl: GUS. 10 March 2011.

- Bielec, Jan (ed.); Szwałek, Stanisława (1982). Wykaz urzędowych nazw miejscowości w Polsce. T. III: P – Ż [List of official names of localities in Poland, Vol. III: P – Ż] (in Polish). Ministry of Administration, Spatial Economy and Environmental Protection (1st ed.). Warsaw, Poland: Central Statistical Office.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Sitek, Janusz (1991). Nazwy geograficzne Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [Geographical names of the Republic of Poland] (in Polish). Ministry of Physical Planning and Construction, Surveyor General of Poland, Council of Ministers' Office, Commission for Establishing Names of Localities and Physiographical Objects (1st ed.). Warsaw, Poland: Eugeniusz Romer State Cartographical Publishing House. ISBN 83-7000-071-1.

- "Staszów, miasto, gmina Staszów — miasto, powiat staszowski, województwo świętokrzyskie" [Staszów, town, Staszów Commune — urban area, Staszów County, Świętokrzyskie Province, Poland]. Topographical map prepared in 1:10,000 scale. Aerial and satellite orthophotomap (in Polish). Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography, Poland, Warsaw. 2011. geoportal.gov.pl. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- סטשוב STASZOW, מרכז מורשת יהודי פולין

- http://www.sztetl.org.pl/he/article/staszow/5,-/ שטעטל וירטואלי

- Megargee, Geoffrey (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. Volume II 319-320. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

- "The Staszow Book". Jewish Gen.

- Lipman, Steve. "Saving Cemeteries Here and Abroad". Jewish Week Media. Jewish Media Week. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Staszów. |

- Official town website

- Sefer Staszow English Translation Online

- Saving Cemeteries Here And Abroad *A Memorial Grows In Staszow

- Website devoted to the memory of Staszow Jews who perished in the Holocaust

- A calendar of Jewish history in Staszowie against the background of important events in the history of the city, foundation for the preservation of Jewish heritage in Poland

- History of Staszów, Poland and its Jewish Community, Dr. N. M. Gelber, jewishgen.org, an extension of the Museum of Jewish Heritage

- History of Staszów, staszow.com

- Kosciuszko's Route on Ziemia Staszowska, staszow.com

- The Royal Opponent, Report about operations of the 71st Independent Guards Heavy Tank Regiment from 14.07.44 to 31.08.44, staszow.com

- Polish official population figures 2006

- Staszów, Poland at JewishGen