St Bertoline's Church, Barthomley

St Bertoline's Church is in the village of Barthomley, Cheshire, England. The church is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building.[1] It is an active Anglican parish church in the diocese of Chester, the archdeaconry of Macclesfield and the deanery of Congleton.[2]

| St Bertoline's Church, Barthomley | |

|---|---|

St Bertoline's Church, Barthomley, from the south | |

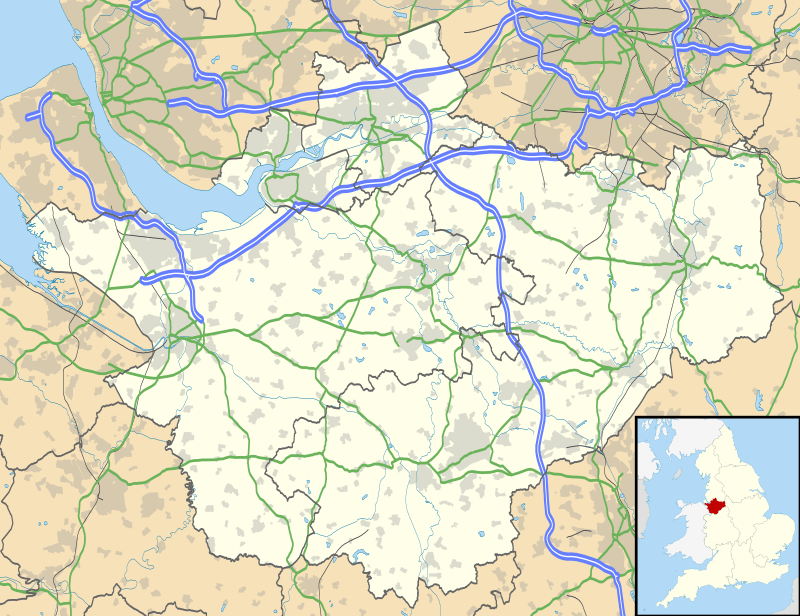

St Bertoline's Church, Barthomley Location in Cheshire | |

| OS grid reference | SJ 767 524 |

| Location | Barthomley, Cheshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | St Bertoline, Barthomley |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Dedication | Saint Bertoline |

| Events | Massacre in the Civil War (1643) |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 12 January 1967 |

| Architect(s) | Austin and Paley (chancel) |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Perpendicular, Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 15th century |

| Completed | 1926 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Red sandstone, lead roof |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Barthomley |

| Deanery | Congleton |

| Archdeaconry | Macclesfield |

| Diocese | Chester |

| Province | York |

| Clergy | |

| Priest(s) | Canon Darrel Speedy |

| Assistant priest(s) | Rev Angela Speedy |

| Laity | |

| Reader(s) | Mike Elkin |

| Director of music | Gill Thorley |

| Churchwarden(s) | Christine Bailey Lynne Evans |

| Parish administrator | Jackey Rockey |

The church stands in the centre of the village,[3] in an elevated position on Barrow Hill, which was an ancient burial ground.[4] It was the scene of a massacre in the Civil War. Richards considered it to be one of the most beautiful churches in the county, and believed it was the only one in England to be dedicated to Saint Bertoline.[5] The church stands above the road and is reached by a flight of steps.[5]

History

The nave and tower date from the late 15th century,[1] and the Crewe chapel from about 1528.[6] There was a restoration of the church between 1852 and 1854.[5] The chancel, designed by Austin and Paley, was built in 1925–26[1] by the Marquess of Crewe as a memorial to family members.[5]

On Christmas Eve 1643, during the civil war, the church was the scene of a massacre. About 20 Parliamentary supporters had taken refuge in the church when Royalist forces under the command of Lord Byron started a fire. The Parliamentarians surrendered but twelve of them were then killed.[5][7][8]

Until 200 years ago it was the parish church of a vast area of southeast Cheshire, and the village was the centre of a very scattered community. Since then, many hamlets within the parish, Alsager, Crewe and Haslington, have blossomed and flourished into parishes of their own, leaving Barthomley at the centre as a parish of about 400 people. The Parochial Church Council has recently overseen the completion of the second stage of a major restoration. The Parochial Church Council is soon to oversee the final stage of restoration.[9]

Architecture

Exterior

The church is built in red sandstone with a lead roof in Perpendicular style.[1] Its oldest part is a Norman blocked doorway in the north wall sited in a gap between the end of the aisle and the vestry,[10] which was moved to its present position in the 19th century.[5]

Its plan consists of a tower at the west end, a four-bay nave with a clerestory, and north and south aisles, a north porch, and a chancel with a vestry to its north. At the east end of the south aisle is the Crewe chapel.[6] The tower dates from the late 15th century. At its west end is a door, above which is a four-light Perpendicular window, two-light bell openings on each side and a clock on the north side.[1] Flanking the bell openings on each side are coats of arms of local families.[11] The summit of the tower is embattled, it has eight crocketted pinnacles and gargoyles at the four corners. The nave and aisles are also embattled. In the porch is the original stone holy water font of the church. The east window has five lights.[1] The camber beam panelled roofs of the nave and north aisle date from the 16th century.[11]

Interior

Many of the old fittings were lost in the 1852–54 restoration but the parclose screen which formerly divided the Crewe Chapel from the chancel was preserved,[5] and it now encloses the organ at the east end of the north aisle.[1] In the church are English oil paintings of Moses and Aaron. The stained glass in the west window is by Clayton and Bell and is dated 1873. The glass in the east window is dated 1925 and is by Shrigley and Hunt.[12] The altar dates from the late 16th century and includes a variety of images, including the Nativity, the flight into Egypt, and two men each carrying a hare and a bird.[5]

In the Crewe Chapel is the recumbent alabaster effigy of Sir Robert de Foulshurst, who distinguished himself at the battle of Poitiers, dressed as a knight in armour with a gorget of mail, a conical helmet and a collar of esses. It is dated around 1390. The side of the tomb chest has Gothic arches underneath which are six male and six female figures. Also in the chapel is the recumbent figure of a clergyman, probably Robert Foulshurst, rector of Barthomley who died in 1529.[5] Later memorials are the marble figure of Lady Houghton who died in 1890 by J. Edgar Boehm, a Victorian Gothic monument to the first Lord Crewe, and two large wall monuments to other members of the Crewe family. In the south wall of the chancel is a two-arched sedilla.[1] There is a ring of eight bells. The oldest six bells were cast by Rudhall of Gloucester, five in 1743 and one in 1747.[5] The three later bells date from 1908 and were cast by Taylor of Loughborough.[13] The parish registers begin in 1562 and the churchwardens' accounts in 1660.[5] The organ was built in 1850 by Forster & Andrews and restored in 1969 by Ward & Shutt, and again in 2003.[14] This organ was replaced in 2005 by a Makin Digital Organ.[15]

Other burials

External features

The churchyard contains the Commonwealth war grave of a World War I New Zealand soldier.[16]

Popular culture

The church is an important location in the novel Red Shift by Alan Garner, which deals largely with the Barthomley massacre of 1643.

See also

- Grade I listed buildings in Cheshire East

- Grade I listed churches in Cheshire

- Norman architecture in Cheshire

- Listed buildings in Barthomley

References

- Historic England, "The Church of St.Bertoline, Barthomley (1330063)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 March 2012

- St Bertoline, Barthomley, Church of England, retrieved 16 February 2011

- Barthomley, Streetmap, retrieved 16 February 2011

- Thornber, Craig (15 February 2002), A Scrapbook of Cheshire Antiquities: Barthomley, retrieved 26 August 2007

- Richards, Raymond (1947), Old Cheshire Churches, London: Batsford, pp. 43–47, OCLC 719918

- Salter, Mark (1995), The Old Parish Churches of Cheshire, Malvern: Folly Publications, p. 22, ISBN 1-871731-23-2

- Plant, David (27 September 2005), "Sir John, Lord Byron c.1599–1652", British Civil Wars, Commonwealth and Protectorate 1638–60, David Plant, retrieved 26 August 2007

- Plant, David (11 May 2006), "1643–64: The Nantwich Campaign", British Civil Wars, Commonwealth and Protectorate 1638–60, David Plant, retrieved 26 August 2007

- Our Church, St Bertoline's, Barthomley, retrieved 26 September 2010

- St Bertoline, Barthomley, Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture of Great Britain and Ireland, archived from the original on 2 August 2012, retrieved 13 June 2010

- Morant, Roland W. (1989), Cheshire Churches, Birkenhead: Countyvise, pp. 103–104, ISBN 0-907768-18-0

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Hubbard, Edward; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2011) [1971], Cheshire, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 122–124, ISBN 978-0-300-17043-6

- Barthomley S Bertoline, Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers, retrieved 9 August 2008

- Cheshire, Barthomley St Bertoline, British Institute of Organ Studies, retrieved 6 August 2008

- Music, St Bertoline's, Barthomley, retrieved 30 December 2010

- GINDERS, GEORGE PERCY, Commonwealth War Graves Commission, retrieved 2 February 2013