St Andrew's Church, Redbourne

St Andrew's Church is a redundant Anglican church in the village of Redbourne, Lincolnshire, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building,[1] and is under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust.[2] The church stands in the centre of the village, which is to the east of the A15 road, and some 4 miles (6 km) south of Brigg.[2][3]

| St Andrew's Church, Redbourne | |

|---|---|

St Andrew's Church, Redbourne, from the south | |

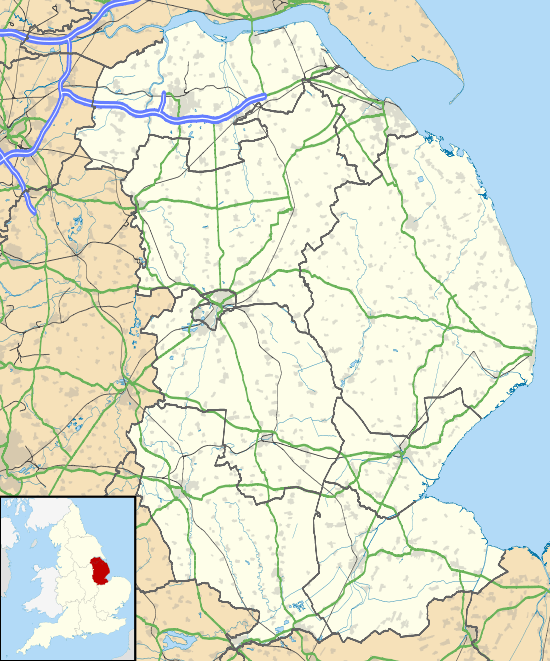

St Andrew's Church, Redbourne Location in Lincolnshire | |

| OS grid reference | SK 973 999 |

| Location | Redbourne, Lincolnshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | Churches Conservation Trust |

| History | |

| Dedication | Saint Andrew |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Redundant |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 6 January 1987 |

| Architect(s) | W. W. Goodhand (restoration) |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Gothic |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Limestone with some rendering |

History

The church dates from the 14th–15th century. Rebuilding took place in the later part of the 18th century; this included new north and south chapels in the 1770s by William and Thomas Lumby of Lincoln. The plaster ceilings date from 1775–77, and the top two stages were added to the tower in 1785. A new west door, partial rebuilding of the aisles, the chancel, and the clerestory, probably also date from this period. The south chapel was rebuilt in early 19th century as a mausoleum for the Dukes of St Albans. The church was restored in 1888 by the local architect W. W. Goodhand. The restorations included removing the gallery, reordering the seating, and the addition of a new south porch.[1] The church was declared redundant in May 1978.[4] A vestry door was inserted and east side windows were removed in about 1985.[1]

Architecture

Exterior

St Andrew's is constructed in limestone with some rendering. The nave, aisles and clerestory have lead roofs; the mausoleum, vestry and porch are slated. Its plan consists of a three-bay nave with a clerestory, north and south aisles, a south porch, a single-bay chancel with a vestry and organ chamber to the north, and the mausoleum to the south, and a west tower. The tower has a rectangular staircase projection to the southeast. It is in four stages, divided by string courses, on a moulded plinth. In the bottom stage on the west side is a blocked doorway, an arched three-light window, and a square-headed two-light window. On the north and south sides are lighting slits. In the staircase turret are three slits, and a sundial. The second stage contains two-light windows, and in the third stage is a clock face on the west side. In the top stage are two-light bell openings, and the parapet is embattled. The aisles have pointed two-light windows and along the clerestory are square-headed two-light windows. In the south aisle there is a blocked doorway to the west, a blocked lancet window to the east, blocked circular windows to the east and west, and a blocked pointed south window. A carved stone dating from the 10th–11th century has been re-set in the west wall. The chancel has an east window. In the vestry are two two-light windows, and the mausoleum has a south door. All the parapets are embattled, some with crocketted pinnacles.[1]

Interior

The arcades are carried on octagonal piers. The ceilings are plastered, the nave ceiling being decorated with foliate bosses. The floors are flagged. The baluster-shaped font was made in 1775 by Richard Hayward. The east window contains painted glass by William Collins dating from about 1840. This is a copy of The Opening of the Sixth Seal (part of the Last Judgment) by Francis Danby. Also by Collins are twelve stained glass windows depicting the Apostles.[1] The organ is no longer present.[5] There is a ring of six bells. Five of these were cast in 1774 by Henry Harrison II, and the undated sixth bell is by James Harrison III.[6]

Memorials

In the north wall of the chancel is a niche containing a black marble graveslab depicting a knight and angels, and is dated 1410. On the south side of the chancel are marble wall tablets to members of the Carter family with dates in the 18th century, and to the 8th Duke of St Albans, who died in 1825, and his wife. On the north side of the chancel is a memorial to the 9th Duke of St Albans who died in 1851 by J. G. Lough, and to his wife, Harriet, who died in 1837, by Chantrey, and a memorial to Charlotte, Lady Beauclerk, dating from about 1825. In the mausoleum are two tiers of tombs of the St Albans family.[1]

External features

In the churchyard is a gravestone dated 1737 to Rev Josias Morgan, vicar of the parish, It is listed at Grade II.[7] There are also the war graves of a soldier of World War I, and another of World War II.[8]

References

- Historic England, "Church of St Andrew, Redbourne (1346524)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 26 September 2013

- St Andrew's Church, Redbourne, Lincolnshire, Churches Conservation Trust, retrieved 9 December 2016

- Redbourne, Streetmap, retrieved 28 February 2011

- Redbourne (Redborn): Church History, GENUKI, retrieved 28 February 2011

- Lincolnshire (Humberside), Redbourne, St. Andrew (D04123), British Institute of Organ Studies, retrieved 28 February 2011

- Redbourne, S Andrew, Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers, retrieved 28 February 2011

- Historic England, "Gravestone approximately 2 metres east of Church of St Andrew, Redbourne (1162289)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 26 September 2013

- REDBOURNE (ST. ANDREW) CHURCHYARD, Commonwealth War Graves Commission, retrieved 1 March 2013