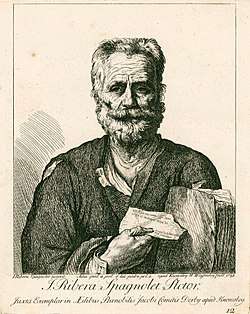

Jusepe de Ribera

Jusepe de Ribera (Valencian: [juˈsepe ðe riˈβeɾa]; 17 February, 1591 (bap.) – 2 September, 1652) was a Spanish Tenebrist painter and printmaker, also known as José de Ribera and Josep de Ribera. He also was called Lo Spagnoletto ("the Little Spaniard") by his contemporaries and early writers.[1] Ribera was a leading painter of the Spanish school, although his mature work was all done in Italy.

Early life

Ribera was born at Xàtiva, near Valencia, Spain, the second son of Simón Ribera and his first wife Margarita Cucó.[1][2] [3]He was baptized on 17 February, 1591.[2] His father was a shoemaker or cobbler, perhaps on a large scale.[2] His parents intended him for a literary or learned career, but he neglected these studies and is said to have apprenticed with the Spanish painter Francisco Ribalta in Valencia,[4] although no proof of this connection exists.[2][5] Longing to study art in Italy, he made his way to Rome via Parma, where he painted Saint Martin and the Beggar, now lost, for the church of San Prospero in 1611.[5] According to one source, a cardinal noticed him drawing from the frescoes on a Roman palace facade, and housed him. Roman artists gave him the nickname "Lo Spagnoletto".

His early biographers generally rank him among the followers of Caravaggio.[5] Very little documentation survives from his early years, with scholars speculating as to the precise time and route by which he came to Italy. Ribera started living in Rome no later than 1612, and is documented as having joined the Academy of Saint Luke by 1613.[5] He lived for a time in the Via Margutta, and almost certainly associated with other Caravaggisti who flocked to Rome at that time, such as Gerrit van Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen, among other Utrecht painters active in Rome by 1615. In 1616, Ribera moved to Naples, in order to avoid his creditors (according to Giulio Mancini, who described him as living beyond his means despite a high income). In November, 1616, Ribera married Caterina Azzolino, the daughter of a Sicilian-born Neapolitan painter, Giovanni Bernardino Azzolino, whose connections in the Neapolitan art world helped to establish Ribera early on as a major figure, whose presence was to bear a lasting impact on the art of the city.[5]

Neapolitan period

The Kingdom of Naples was then part of the Spanish Empire, and ruled by a succession of Spanish Viceroys. Ribera moved to Naples permanently in the middle of 1616.[6] His Spanish nationality aligned him with the small Spanish governing class in the city, and also with the Flemish merchant community, from another Spanish territory, who included important collectors of and dealers in art. Ribera began to sign his work as "Jusepe de Ribera, español" ("Jusepe de Ribera, Spaniard"). He was able to quickly attract the attention of the Viceroy, Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna, also recently arrived, who gave him a number of major commissions, which showed the influence of Guido Reni.

The period after Osuna was recalled in 1620 seems to have been difficult. Few paintings survive from 1620 to 1626; but this was the period in which most of his best prints were produced. These were at least partly an attempt to attract attention from a wider audience than Naples. His career picked up in the late 1620s, and he was accepted as the leading painter in Naples thereafter. He received the Order of Christ of Portugal from Pope Urban VIII in 1626.[5]

Although Ribera never returned to Spain,[5] many of his paintings were taken back by returning members of the Spanish governing class, for example the Duke of Osuna, and his etchings were brought to Spain by dealers. His influence can be seen in Velázquez, Murillo, and most other Spanish painters of the period.

He has been portrayed as selfishly protecting his prosperity, and is reputed to have been the chief in the so-called Cabal of Naples, his abettors being a Greek painter, Belisario Corenzio and the Neapolitan, Giambattista Caracciolo.

It is said this group aimed to monopolize Neapolitan art commissions, using intrigue, sabotage of work in progress, and even personal threats of violence to frighten away outside competitors such as Annibale Carracci, the Cavalier d'Arpino, Reni, and Domenichino. All of them were invited to work in Naples, but found the place inhospitable. The cabal ended at the time of Domenichino's death in 1641.

De Ribera's pupils included the Flemish painter Hendrick de Somer, Francesco Fracanzano, Luca Giordano, and Bartolomeo Passante. He was followed by Giuseppe Marullo and influenced the painters Agostino Beltrano, Paolo Domenico Finoglio, Giovanni Ricca, and Pietro Novelli.[8]

Later life

About 1644, his daughter married a Spanish nobleman in the administration, who died soon after. From 1644, Ribera seems to have suffered serious ill-health, which greatly reduced his ability to work, although his workshop continued to produce works under his direction. In 1647–1648, during the Masaniello rising against Spanish rule, he felt forced for some months to take his family with him into refuge in the palace of the Viceroy. In 1651 he sold the large house he had owned for many years, and when he died on 2 September, 1652, he was in serious financial difficulties.

Work

In his earlier style, founded sometimes on Caravaggio and sometimes on the wholly diverse method of Correggio, the study of Spanish and Venetian masters may be traced. Along with his massive and predominating shadows, he retained from first to last a great strength in local coloring. His forms, although ordinary and sometimes coarse, are correct; the impression of his works gloomy and startling. He delighted in subjects of horror. In the early 1630s his style changed away from strong contrasts of dark and light to a more diffused and golden lighting, as may be seen in The Clubfoot of 1642.

Salvator Rosa and Luca Giordano were his most distinguished followers, who may have been his pupils; others were also Giovanni Do, the Flemish painter Hendrick de Somer (known in Italy as 'Enrico Fiammingo'), Michelangelo Fracanzani, and Aniello Falcone, who was the first considerable painter of battle-pieces.

Among Ribera's principal works could be named Saint Januarius Emerging from the Furnace in the cathedral of Naples; the Descent from the Cross in the Certosa, Naples; the Adoration of the Shepherds (a late work; 1650) in the Louvre; the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew in the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona; and the Pieta in the sacristy of San Martino, Naples. His mythologic subjects are often as violent as his martyrdoms: for example, Apollo and Marsyas, with versions in Brussels and Naples, or the Tityos in the Prado. The Prado owns fifty six paintings and other six attributed to Ribera, algonside with eleven drawings, like Jacob’s Dream (1639); Louvre contain four of his painting and seven drawings; the National Gallery, London, three; The Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando owns a nice ensamble of five paintings including The Assumption of Mary Magdalene from El Escorial, an early Ecce Homo or The head of St. John the Baptist. He executed several fine male portraits and a self-portrait. Saint Jerome Writing in the Prado now has been credited to him by Gianni Papi, a Caravaggio expert. He was an important etcher, the most significant Spanish printmaker before Goya, producing about forty prints, nearly all in the 1620s. The Martyrdom of Saint Philip (1639; often described as Saint Bartholomew, martyred in similar fashion, but now recognised as St Philip)[9] is in the Prado, Madrid.

Legacy

Ribera's work remained in fashion after his death, largely through the hyper-naturalistic depictions of cruel subjects in the paintings of such pupils as Luca Giordano.[10] According to the 1911 11th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica "His forms, though ordinary and partly gross, are correct; the impression of his works gloomy and startling. He delighted in subjects of horror."[11] He painted the horrors and reality of human cruelty and showed he valued truth over idealism. The gradual rehabilitation of his international reputation was aided by exhibitions in Princeton in 1973, of his prints and drawings, and of works in all media in London at the Royal Academy in 1982 and in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1992. Since then his oeuvre has gained more attention from critics and scholars. Unfortunately, due to the ebb of interest in his work for so long, a complete catalogue raisonné of his work is still lacking. Many works attributed to him have been altered, discarded, damaged, and neglected during his period of obscurity.[10]

- Selected works

.jpg)

The Assumption of Mary Magdalene[13], 1636, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid.

The Assumption of Mary Magdalene[13], 1636, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid. Saint Jerome, 1652. Prado Museum, Madrid.[14]

Saint Jerome, 1652. Prado Museum, Madrid.[14] The denial of St Peter, c. 1615

The denial of St Peter, c. 1615 Ecce Homo[15], 1620. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid.

Ecce Homo[15], 1620. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid. The Holy Family, 1639. Museum of Santa Cruz, Toledo.

The Holy Family, 1639. Museum of Santa Cruz, Toledo. The Pietà[16], 1633, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid.

The Pietà[16], 1633, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid.

Notes

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

- Grovier, Kelly. "Ribera: Was this the vision of a sadist?". Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Finaldi, Gabriele (1992). "A documentary look at the life and work of Jusepe de Ribera". In Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E.; Spinosa, Nicola (eds.). Jusepe de Ribera 1591–1652. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 3. ISBN 9780870996474.

- "Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish / Italian, Spanish/ Italian, 1591 – 1652) (Getty Museum)". The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "Jusepe de Ribera". Sartle – Rogue Art History. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "Artist Info". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Spinosa, Nicola (2012). "Neapolitan Painters in Rome (1600-1630)". In Rosella Vodret (ed.). Caravaggio's Rome: 1600–1630 (paperback). Milan: Skira Editore S.p.A. pp. 331–343. ISBN 978-88-572-1387-3.

- Fernando, Real Academia de BBAA de San. "Borbón, Francisco de Paula Antonio de". Academia Colecciones (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Jusepe Ribera at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- [See Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, 1996, p. 315, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, ISBN 84-87317-53-7]

- Johnson, Paul. Art: A New History, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003.

- "Giuseppe Ribera", in Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.)

- "Ixión - Colección - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Fernando, Real Academia de BBAA de San. "Ribera, José - Ecce Homo". Academia Colecciones (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "The penitent Saint Jerome - The Collection - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Fernando, Real Academia de BBAA de San. "Ribera, José - Ecce Homo". Academia Colecciones (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "The Pietà". Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

References

- Main source: Scholz-Hänsel, Michael. (2000). Jusepe de Ribera, 1591–1652. Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 3-8290-2872-5

Further reading

- Brown, Jonathan. (1973). Jusepe de Ribera: prints and drawings; [catalogue of an exhibition] The Art Museum, Princeton University, October–November 1973. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University. OCLC 781367 the standard work on his prints and drawings.

- Sánchez, Alfonso E. Pérez (1992). Jusepe de Ribera, 1591–1652. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870996474. [full text resource]

- Williamson, Mark A. "The Martyrdom Paintings of Jusepe de Ribera: Catharsis and Transformation"; PhD Dissertation, Binghamton University, Binghamton, New York 2000 (available online at myspace.com/markwilliamson13732) (link broken)

External links

- 35 paintings by or after Jusepe de Ribera at the Art UK site

- The bearded woman, Work of the month – Ducal House of Medinaceli Foundation