Hendrick de Somer

Hendrick de Somer, often erroneously referred to as Hendrick van Someren or Hendrick van Somer, known in Italy as Enrico Fiammingo and Henrico il Fiamingo (Lokeren or Lochristi, 1607 – probably Naples, c. 1655) was a Flemish painter who spent most of his life and career in Italy where he was mainly active in Naples. He was known for his religious and mythological compositions and occasional genre painting. His style was initially influenced by the Spanish painter Jusepe de Ribera who worked in Naples and was a follower of Caravaggio. Later the painter became influenced by the neo-Venetian and Bolognese schools. He is considered one of the leading Netherlandish painters working in Naples in the first half of the 17th century.[1]

Life

Hendrick de Somer is generally identified with the 'Enrico Fiammingo' mentioned as a pupil of Jusepe de Ribera by the Italian art historian and painter Bernardo de' Dominici in the Vite dei Pittori, Scultori, ed Architetti Napolitani (Lives of the Neapolitan Painters, Sculptors, and Architects) (1742-1743).[2] Until quite recently the artist was confused with a Dutch painter from Amsterdam with an almost identical name called Hendrick van Someren or Hendrick van Somer.[3] The credit for discovering the true identity of Hendrick de Somer is due to Ulisse Prota-Giurleo who discovered a record of an 'Enrico de Somer' acting as a witness in a legal procedure relating to the marriage of the painter Viviano Codazzi in Naples.[1] In the document the painter stated that he was at the time 29 years old and had lived in Naples for 12 years. This statement makes it possible to identify the year of his birth as 1607 and to fix the year of his arrival in Naples as 1624. The statement further names the artist's father as 'Gil'.[4]

Further research by art historians revealed that Hendrick de Somer had left Flanders for Italy where he settled in Naples in 1624. He may have travelled with his family or have been received by a family member already resident in Naples.[1][5] He remained active in that city until 1655.[5]

Not long after arriving in Naples, de Somer was admitted to the workshop of Jusepe de Ribera, the leading Spanish painter in Naples at the time. He married a local woman with whom he had children.[5] He had close links with artists in Naples such as Viviano Codazzi and Domenico Gargiulo with whom he also collaborated. He was also familiar with the Dutch artist Matthias Stom who worked in Naples in the 1630s.[1] He was a Kirchmeister (church master) of the German-Flemish brotherhood in Naples. During Somer's residence the Flemish community in Naples had become smaller than in the early 16th century when artists such as Louis Finson were active in the city. This explains why de Somer became so fully integrated in Naples' social and artistic communities and became more a Neapolitan than a Flemish painter.[5]

There are no records about Hendrick de Somer after 1656, indicating that he may have been one of the victims of the 1656 plague in Naples.[2]

Work

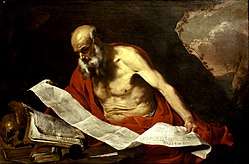

The catalogue of works of Hendrick de Somer compiled in 2014 contained 87 works.[6] His works deal principally with biblical and mythological subject matter. The attributions of work to Hendrick de Somer are based principally on the only three signed and dated works by de Somer: the Caritas Romana of 1635 in a private Roman collection and two versions of St. Jerome in the desert, one in the Trafalgar Galleries in London from 1651, the other in the Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Barberini in Rome from 1652. The latter originally carried a fake de Ribera signature, which had been painted over the signature 'Enrico So[mer] f. and the date '1652'. Another key work for identifying the artist's work is the altarpiece of the Baptism of Christ (Naples, Santa Maria della Sapienza) of 1641, which can be attributed with certainty to de Somer since the documentation relating to its commission has been preserved.[1] This early work shows the artist's close connection with de Ribera. In particular it shows similarities with the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian of Ribera (Museo di Capodimonte). Another influence in this work is the Flagellation of Christ of Caravaggio.[7] Later, like many of his Neapolitan colleagues, de Somer moved away from de Ribera's tenebrism in response to the growing taste for Roman-Bolognese art in Naples. His work shows no trace of his Northern origins.[5]

De Somer is believed to have been in contact with Matthias Stom during the latter's stay in Naples in the 1630s. Hendrick's works such as Caritas Romana (1635, private collection) and Tobias curing his father's blindness (c. 1635, Banco Commerciale Italiana, Collezione Intesa Sanpaolo) can be seen as de Somer's reaction to the northern realism of Matthias Stom.[7]

In later compositions de Somer reflects influences deriving from the example of other Neapolitan masters who asserted themselves in those years, such as Massimo Stanzione and Bernardo Cavallino. Hendrick's palette moved gradually away from the tenebrism of Ribera and opened up to the neo-Venetian color, which in that period came to replace the chiaroscuro of the Caravaggisti.[2] Works like his multiple versions of Lot and his daughters and his Samson and Delilah are examples of this evolution.[7]

A work with a certain later date is the Saint Jerome reading of 1652 (Rome, Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Barberini). De Somer created many paintings of the saint, as did his master de Ribera who had popularised this theme.[1]

Notes

- Damian, Veronique et Chiara Naldi, Massimo Stanzione, Guercino, Hendrick de Somer et Fra' Galgario, Paris: Galerie Canesso, 2016, pp. 20–25

- Francesco Abbate, Storia dell’arte nell’Italia Meridionale. Vol. IV. Il secolo d’oro, Roma, 2002, p. 101 (in Italian)

- See: G.J. Hoogewerff, 'Hendrick van Somer, schilder. Navolger van Ribera', Oud-Holland 60 (1943), pp. 158–172 (in Dutch)

- Ulisse Prota-Giurleo, Pittori napoletani del '600, Fausto Fiorentino, 1953, p. 77 (in Italian)

- M.G.C. Osnabrugge, Netherlandisch Immigrant Painters in Naples (1575-1654). Aert Mytens, Louis Finson, Abraham Vinck, Hendrick De Somer and Matthias Stom, University of Amsterdam, 2015, pp. 152–153

- Giuseppe Porzio, La scuola di Ribera. Giovanni Do, Bartolomeo Passante, Enrico Fiammingo, Naples, 2014, pp. 107-108 (in Italian)

- Viviana Farina, Intorno a Ribera. Nuove riflessioni su Giovanni Ricca e Hendrick van Somer e alcune aggiunte ai giovani Ribera e Luca Giordano, Naples, 2012, p. 31 (in Italian)

External links

![]()