Southwestern archaeology

Southwestern archaeology is a branch of archaeology concerned with the Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico. This region has long been occupied by hunter-gatherers and agricultural peoples.

This area, identified with the current states of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada in the western United States, and the states of Sonora and Chihuahua in northern Mexico, has seen successive prehistoric cultural traditions for a minimum of 12,000 years. An often-quoted statement from Erik Reed (1964) defined the Greater Southwest culture area as extending north to south from Durango, Mexico, to Durango, Colorado, and east to west from Las Vegas, Nevada, to Las Vegas, New Mexico.[1] Differently areas of this region are also known as the American Southwest, North Mexico, and Oasisamerica, while its southern neighboring cultural region is known as Aridoamerica or Chichimeca.[1]

Many contemporary cultural traditions exist within the Greater Southwest, including Yuman-speaking peoples inhabiting the Colorado River valley, the uplands, and Baja California, O'odham peoples of Southern Arizona and northern Sonora, and the Pueblo peoples of Arizona and New Mexico. In addition, the Apache and Navajo peoples, whose ancestral roots lie in the Athabaskan-speaking peoples in eastern Alaska and western Canada, entered the Southwest prior to European contact.

Paleo-Indian tradition

Paleo-Indians, according to most archaeologists, initially followed herds of big game—megafauna such as mastodon and bison[2]—into North America. The traveling groups also collected and utilized a wide variety of smaller game animals, fish, and a wide variety of plants.[3] These people were likely characterized by highly mobile bands of approximately 20 or 50 members of an extended family, moving from place to place as resources were depleted and additional supplies needed.[4] Paleoindian groups were efficient hunters and created and carried a variety of tools, some highly specialized, for hunting, butchering and hide processing. The earliest habitation of Paleo-Indians in the American Southwest dates to about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, and evidence from this tradition ranges from 10,500 BCE to 7500 BCE. These paleolithic people utilized habitat near water sources, including rivers, swamps and marshes, which had an abundance of fish, and drew birds and game animals. Big game, including bison, mammoths and ground sloths, also were attracted to these water sources. At the latest by 9500 BCE, bands of hunters wandered as far south as Arizona, where they found a desert grassland and hunted mule deer, antelope and other small mammals.

As populations of larger game began to diminish, possibly as a result of intense hunting and rapid environmental changes, Late Paleoindian groups would come to rely more on other facets of their subsistence pattern, including increased hunting of bison, mule deer and antelope. Nets and the atlatl to hunt water fowl, ducks, small animals and antelope. Hunting was especially important in winter and spring months when plant foods were scarce.

Southwestern Archaic tradition

The Archaic time frame is defined culturally as a transition from a hunting/gathering lifestyle to one involving agriculture and permanent, if only seasonally occupied, settlements. In the Southwest, the Archaic is generally dated from 8000 years ago to approximately 1800 to 2000 years ago.[5] During this time the people of the southwest developed a variety of subsistence strategies, all using their own specific techniques. The nutritive value of weed and grass seeds was discovered and flat rocks were used to grind flour to produce gruels and breads. This use of grinding slabs in about 7500 BCE marks the beginning of the Archaic tradition. Small bands of people traveled throughout the area, gathering plants such as cactus fruits, mesquite beans, acorns, and pine nuts and annually establishing camps at collection points.

Late in the Archaic Period, corn, probably introduced into the region from central Mexico, was planted near camps with permanent water access. Distinct types of corn have been identified in the more well-watered highlands and the desert areas, which may imply local mutation or successive introduction of differing species. Emerging domesticated crops also included beans and squash.

About 3,500 years ago, climate change led to changing patterns in water sources, leading to dramatically decreaseds population. However, family-based groups took shelter in south facing caves and rock overhangs within canyon walls. Occasionally, these people lived in small semisedentary hamlets in open areas. Evidence of significant occupation has been found in the northern part of the Southwest range, from Utah to Colorado, especially in the vicinity of modern Durango, Colorado.

Archaic cultural traditions include:

- Archaic–Early Basketmaker Era (7000–1500 BCE)

- Sand-Dieguito-Pinto (6500 BCE–200 CE)

- Oshara (5500 BCE–600 CE)

- Cochise (before 5000 BCE–200 CE)

- Chihuahua (6000 BCE–250 CE)

Post-Archaic cultures

The American Indian archaic culture eventually evolved into three major prehistoric archaeological culture areas in the American Southwest and Northern Mexico. These cultures, sometimes referred to as Oasisamerica, are characterized by dependence on agriculture, formal social stratification, population clusters and major architecture.

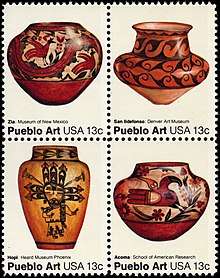

- The culture of Ancestral Pueblo peoples, formerly referred to as the Anasazi, was centered around the present-day Four Corners area. Their distinctive pottery and dwelling construction styles emerged in the area around 750 CE, though the origins of their hallmark material culture characteristics can be found within the Basketmaker II Period (1500 BCE–400 CE).[6] Ancestral Pueblo peoples are renowned for the construction of and cultural achievement present at Pueblo Bonito and other sites in Chaco Canyon, as well as Mesa Verde, Aztec Ruins, and Salmon Ruins.

- The Hohokam tradition, centered on the middle Gila River and lower Salt River drainage areas, and extending into the southern Sonoran Desert, is believed to have emerged in approximately 200 CE. These people lived in smaller settlement clusters than their neighbors, and built extensive irrigation canals for a wide range of agricultural crops. There is evidence the Hohokam had far-reaching trade routes with ancient Mesoamerican cultures to the south, and show cultural influences from these southerners. A defining moment of the Classic Hohokam is the emergence of Salado culture, likely a product of ethnogenesis with an influx of migrating Kayenta Anasazi[7]

- Mogollon peoples /moʊɡəˈjoʊn/ lived in the southwest from approximately 200 CE until sometime between 1450 and 1540 CE. Archaeological sites attributed to the Mogollon are found in the Gila Wilderness, Mimbres River Valley, along the Upper Gila river, Paquime and Hueco Tanks, an area of low mountains between the Franklin Mountains to the west and the Hueco Mountains to the east.

In addition, three distinct minor cultures inhabited the eastern, western, and northern extremes of the area. From 1200 CE into the historic era a people collectively known as the La Junta Indians lived at the junction of the Conchos River and Rio Grande. Several Spanish explorers described this culture which was related to or derivative from the Jornada Mogollon.[8] Between 700 and 1550 CE, the Patayan culture inhabited parts of modern-day Arizona, California and Baja California, including areas near the Colorado River Valley, nearby uplands, and north to the vicinity of the Grand Canyon. The Fremont culture inhabited sites in what is now Utah and parts of Nevada, Idaho and Colorado from 700 to 1300 CE.

Cultural distinctions

Archaeologists use cultural labels such as Mogollon, Ancestral Pueblo peoples, Patayan, or Hohokam to denote cultural traditions within the prehistoric American Southwest. It is important to understand that culture names and divisions are assigned by individuals separated from the actual cultures by both time and space. This means that cultural divisions are by nature arbitrary, and are based solely on data available at the time of each analysis and publication. They are subject to change, not only on the basis of newly discovered information, but also as attitudes and perspectives change within the scientific community. It cannot be assumed that an archaeological division corresponds to a particular language group or to any social or political entity, such as a tribe.

When making use of modern archaeological definitions of cultural divisions, in the Southwest or other areas, it is important to understand three specific limitations in the current conventions.

- Artifact based: Archaeological research focuses on enduring evidence, items left behind during people’s activities. Scientists are able to examine fragments of pottery vessels, human remains, stone tools or evidence left from the construction of buildings and shelters. However, other aspects of the culture of prehistoric peoples, such as language, beliefs and behavior patterns, are not tangible.

- Cultural divisions: cultural identifiers are tools of the modern scientist, and so should not be considered similar to divisions or any social relationships the ancient residents may have recognized. Modern cultures in this region, many of whom claim some of these ancient people as ancestors, display a striking range of diversity in lifestyles, language and religious beliefs. This suggests the ancient people were also more diverse than their material remains may suggest.

- Cultural variants: The modern term “style” has a bearing on how material items such as pottery or architecture should be interpreted. Subsets of a larger group can adopt different means to accomplish the same end. For example, in modern Western cultures, there are alternative styles of clothing that characterized older and younger generations, and subgroups within a given generation. Some cultural differences may be based on linear traditions, on teaching from one generation or “school” to another. Other variants in style may distinguish arbitrary groups within a culture, perhaps defining social status, gender, clan or guild affiliation, religious belief or cultural alliances. Variations may also simply reflect the available resources in given time or area.

Sharply defining cultural groups tends to create an image of group territories separated by clear-cut boundaries, similar to modern nation states. These simply did not exist. Prehistoric people traded, worshiped and collaborated most often with other nearby groups. Cultural differences should therefore be understood as "clinal", "increasing gradually as the distance separating groups also increases." [9] Departures from the expected pattern may occur because of unidentified social or political situations or because of geographic barriers. In the Southwest, mountain ranges, rivers and, most obviously, the Grand Canyon, can be significant barriers for human communities, likely reducing the frequency of contact with other groups. Current opinion holds that the closer cultural similarity between the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo peoples and their greater differences from the Hohokam and Patayan is due to both the geography and the variety of climate zones in the American Southwest.

See also

References

- Cordell, Linda S. and Maxine E. McBrinn 2012 Archaeology of the Southwest, 3rd edition. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek

- Breitburg, Emanual; John B. Broster; Arthur L. Reesman; Richard G. Strearns (1996). "Coats-Hines Site: Tennessee's First Paleoindian Mastodon Association". Current Research in the Pleistocene. 13: 6–8.

- "Kincaid Shelter". Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- Kelly, Robert L.; Lawrence C. Todd (1988). "Coming into the Country: Early Paleoindian Hunting and Mobility". American Antiquity. 53 (2): 231–244. doi:10.2307/281017. JSTOR 281017.

- Cordell, Linda S. (1994) Ancient Pueblo Peoples, p. 34. St. Remy Press and Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-89599-038-5.

- Matson, R (2006). "What is Basketmaker II?". Kiva. 72 (2): 149–165.

- Clark, Jeffery; Lyons, Patrick (2012). Migrants and Mounds: Classic Period Archaeology of the Lower San Pedro Valley. Tucson, Arizona: Archaeology Southwest.

- Miller, Myles R. and Kenmotsu, Nancy A. "Prehistory of the Mogollon and Eastern Trans-Pecos Regions of West Texas." in Perttula, Timothy K. The Prehistory of Texas. College Station: TX A & M Press, 2004, pp. 205–265

- Plog, Stephen (1997) Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest, p. 72. Thames and Hudson, London, England