Acacia aneura

Acacia aneura, commonly known as mulga or true mulga, is a shrub or small tree native to arid outback areas of Australia. It is the dominant tree in the habitat that it gives its name to (mulga) that occurs across much of inland Australia. Specific regions have been designated the Western Australian mulga shrublands in Western Australia and Mulga Lands in Queensland.

| Mulga | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Clade: | Mimosoideae |

| Genus: | Acacia |

| Species: | A. aneura |

| Binomial name | |

| Acacia aneura | |

| |

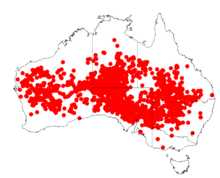

| Occurrence data from AVH | |

Description

Mulga trees are highly variable, in form, in height, and in shape of phyllodes and seed pods. They can form dense forests up to 15 metres (49 ft) high, or small, almost heath-like low shrubs spread well apart. Most commonly, mulgas are tall shrubs. Because the mulga is so variable, its taxonomy has been studied extensively, and although A. aneura is likely to be split into several species eventually, there is as yet no consensus on how or even if this should be done. Although generally small in size, mulgas are long-lived, a typical life span for a tree undisturbed by fire is of the order of 200 to 300 years.

Mulga has developed extensive adaptations to the Australian desert. Like many Acacia species, it has thick-skinned phyllodes. These are optimised for low water loss, with a high oil content, sunken stomata, and a profusion of tiny hairs which reduce transpiration. During dry periods, mulgas drop much of their foliage to the ground, which provides an extra layer of mulch and from where the nutrients can be recycled.

Like most Australian Acacia species, mulga is thornless.[2] The needle-like phyllodes stand erect to avoid as much of the midday sun as possible and capture the cooler morning and evening light. Any rain that falls is channeled down the phyllodes and branches to be collected in the soil immediately next to the trunk, providing the tree with a more than threefold increase in effective rainfall. Mulga roots penetrate far into the soil to find deep moisture. The roots also harbour bacteria that fix atmospheric nitrogen and thus help deal with the very old, nutrient-poor soils in which the species grows.

Habitat and ecology

Mulga savanna and mulga codominant tussock grasslands cover roughly 20% of the Australian continent, or about 1.5 million square kilometres. The mean rainfall for much of the habitat for A. aneura in Australia is roughly 200–250 mm/year, but it goes to as high as 500 mm/year in New South Wales and Queensland. The lowest mean rainfall where it grows is about 50–60 mm/year.[3] Both summer and winter rainfall are necessary to maintain mulga, and the species is absent from semiarid regions that experience summer or winter drought.[4]

Mulga scrub is distinctive and widespread, with the Mulga Lands of eastern Australia defined as a specific bioregion. The dominant species in these woodlands is mulga, with poplar box (Eucalyptus populnea) forming an increasingly important codominant in the eastern districts.[5][6] The extent of ground cover in mulga woodlands varies with canopy density of the overstorey, becoming almost nonexistent in extremely dense stands. In more open stands, the herbaceous layer consists of wire grasses (Aristida spp.), mulga oats (Monocather sp.), mulga mitchell (Thyridolepis sp.), wanderrie (Eriachne spp.), finger grasses (Digitaria spp.) and love grasses (Eragrostis spp.). Various other woody species are also significant in mulga woodlands, particularly hop bushes (Dodonaea spp.), Eremophila and cassia (Senna spp.).[4][6]

In contrast to the eucalypt woodlands that dominate much of Australia, mulga woodlands are not well adapted to regular fire and species in mulga communities vary in their ability to survive fires.[7][8] Many species, including mulga, have a very limited ability to resprout after fire, and rely instead on mechanisms of seed production for species survival. Many plants produce hard, woody fruits or seeds, which can not only survive intense heat, but also may require the stimulus of fire to scarify and promote germination. Long-lived seed stores in soil is also common in these woodlands.[8][9][10]

The recognised varieties are:

Uses

Agriculture

Mulga can be planted with sandalwood in plantations as a host tree. The tree's flowers provide forage for bees, especially when there is enough water available.[11]

Mulga is of great economic importance to the Australian pastoral industry. Despite containing considerable amounts of indigestible tannins, mulga leaves are a valuable fodder source, particularly in times of drought, as they are palatable to stock and provide up to 12% crude protein.[11]

The seeds of Acacia aneura were once used to make seedcakes. The mulga apple is an insect gall commonly eaten by aboriginal people.[12] Mulga tree gum (ngkwarle alkerampwe in the Arrernte language) is a type of lerp scale found on mulga branches. It provides a tasty, honey-like treat.[11]

Wood

Wood from Acacia aneura stands up very well to being buried in soil, so it's used for posts. The wood has a density of about 850–1100 kg/m3.[11] It is also good as firewood, and good-quality charcoal can be produced from it.[11]

Mulga was a vital tree to indigenous Australians in Central Australia; the wood was a good hardwood for making various implements, such as digging sticks, woomeras, shields and wooden bowls.[13]

References

Notes

- "Acacia aneura". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019. 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arid Zone Trees Archived June 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- FAO

- Weston, E. J. (1988). Native Pasture Communities. Native pastures in Queensland their resources and management. W. H. Burrows, J. C. Scanlan and M. T. Rutherford. Brisbane, Department of Primary Industries.

- Harrington, G. N., D. M. D. Mills, et al. (1984). Semi-arid woodlands. Management of Australia's Rangelands. G. N. Harrington and A. D. Wilson. Melbourne, CSIRO Publishing.

- Burrows, W. H., J. O. Carter, et al. (1990). "Management of savannas for livestock production in north-east Australia: contrasts across the tree-grass continuum." Journal of biogeography 17: 503-512.

- Hodgkinson, K. C., G. N. Harrington, et al. (1984). Management of vegetation with fire. Management of Australia’s Rangelands. G. N. Harrington and A. D. Wilson. Melbourne, CSIRO Publishing.

- Dyer, R., A. Craig, et al. (1997). Fire in northern pastoral lands. Fire in the management of northern Australian pastoral lands. T. C. Grice and S. M. Slatter. St. Lucia, Australia, Tropical Grassland Society of Australia.

- White, M. E. (1986). The Greening of Gondwana. Frenchs Forest, Australia, Reed Books.

- Hodgkinson, K. C. (1991). "Shrub recruitment response to intensity and season of fire in a semi-arid woodland." Journal of Applied Ecology 28: 60-70.

- World AgroForestry Centre

- J. H. Maiden (1889). The useful native plants of Australia : Including Tasmania. Turner and Henderson, Sydney.

- "Aboriginal Plant use and Technology" (PDF). Australian National Botanic Garden. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

General references

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acacia aneura. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Acacia aneura |

- "Acacia aneura". Flora of Australia Online. Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government.

- "Acacia aneura". FloraBase. Western Australian Government Department of Parks and Wildlife.

- Mitchell, A. A.; Wilcox, D. G. (1994). Arid Shrubland Plants of Western Australia, Second and Enlarged Edition. University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, Western Australia. ISBN 1-875560-22-X.