South Korean defectors

South Korean defectors are South Korean citizens who have defected to North Korea. After the Korean War, 333 South Korean prisoners of war detained in North Korea chose to stay in the country. During subsequent decades of the Cold War, some people of South Korean origin defected to North Korea as well. They include Roy Chung, a former U.S. Army sergeant who defected to North Korea through East Germany in 1979. North Korea has been accused of abduction in the disappearances of some South Koreans.

Occasionally, North Koreans who have defected to South Korea decided to return. Since South Korea does not permit its naturalized citizens to travel to the North, they have made their way into their home country illegally and thus become "double defectors". From a total of 25,000 North Korean defectors living in South Korea about 800 are missing, some of whom may have returned to the North. During the first half of 2012, the South Korean Ministry of Unification officially recognizes only 13 defections.

Background

The propaganda value of defectors has been recognized even immediately after the Division of Korea in 1945. Defectors were used as tools to prove the superiority of the political system of the country of destination.[1]

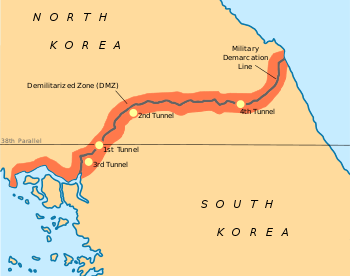

North Korean propaganda has targeted South Korean soldiers patrolling at the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).[2]

Aftermath of the Korean War

A total of 357 prisoners of war detained in North Korea after the Korean War chose to stay in North Korea rather than be repatriated home to the South. These included 333 South Koreans, 23 Americans, and one Briton. Eight South Koreans and two of the Americans later changed their mind.[1] However, the exact number of prisoners of war held by North Korea and China has been disputed since 1953, due to unaccounted South Korean soldiers. Several South Koreans defected to the North during the cold war: In 1953, Kim Sung Bai, a captain in the South Korean air force, defected to North Korea with his F51 Mustang.[3] In 1985, Ra il Ryong, a South Korean private, defected to North Korea and requested asylum.[4] In 1988, a Korean employee at a U.S. army unit in South Korea defected to North Korea. His name was Son Cahng-gu, a transport officer.[5]

During the Cold War, several U.S. Army servicemen defected to North Korea. One of them, Roy Chung, was born to South Korean immigrants. Unlike the others who defected across the DMZ, he defected by first crossing the border between West and East Germany in 1979.[1] His parents accused North Korea of abducting him. The United States was not interested in investigating the case, as he was not a "security risk", and in similar cases it was usually impossible to prove that a kidnapping had occurred. There were several other cases of South Koreans mysteriously disappearing and moving to North Korea at that time, including the case of a geology teacher from Seoul who disappeared in April 1979 while he was having a holiday in Norway. Some South Koreans also accused North Korea of attempting to kidnap them while staying abroad. These alleged kidnapping attempts occurred mainly in Europe, Japan or Hong Kong.[6]

Double defectors

There are people who have defected from North Korea to South Korea, and then have defected back to North Korea again. In the first half of 2012 alone, there were 100 cases of "double defectors" like this. Possible reasons for double defectors are the safety of remaining family members left behind, North Korea's promises of forgiveness and other attempts to lure the defectors back including propaganda,[7] and widespread discrimination faced in South Korea.[8][9] Both the poor and members of elite are dismayed to find out that they are societally worse off in South Korea than they were in the North. Half of the North Korean defectors living in South Korea are unemployed.[10] In 2013, there were 800 North Korean defectors unaccounted for out of 25,000 people. They might have gone to China or Southeast Asian countries on their way back to North Korea.[11] South Korea's Unification Ministry officially recognizes only 13 cases of double defectors as of 2014.[12]

South Korea's laws do not allow naturalized North Koreans to return. North Korea has accused South Korea of abducting and forcibly interning those who want to and has demanded that they be allowed to leave.[13][14][15]

Contemporary South Korean-born defectors

North Korea has targeted its own defectors with propaganda in attempts to lure them back as double defectors,[7] but contemporary South Korean defectors born outside of North Korea were not welcome to defect to the North. In recent years there have been seven people who tried to leave South Korea, but they were detained for illegal entry in North Korea, and ultimately repatriated.[16][17][18] As of 2019, there are reportedly 5461 former South Korean citizens living in North Korea.[19]

There has also been fatalities as a result of failed defections. One defector died in a failed murder-suicide attempt by her husband while in detention.[18] One person who attempted to defect was shot and killed by South Korean military forces in September 2013.[20]

This is an incomplete list of notable cases of defections from South Korea to North Korea.

- 1986

- Choe Deok-sin, a former South Korean Foreign Minister defected with his wife, Ryu Mi-yong, to North Korea.[21]

- 1998

- 2004

- A South Korean soldier was arrested for violating the National Security Law by secretly crossing into North Korea and providing information about the military unit he served in. Deported by the North as an illegal entrant and repatriated to South Korea from China, he was suspected of providing military information to North Korea like the location of the Air Force fighter wing he served in and the location of anti-air batteries.[24]

- 2005

- A 57-year-old South Korean fisherman crossed the eastern maritime border into North Korea. South Korean coastal border guards fired some 20 warning shots from a 60 mm mortar, 106 mm recoilless rifle and MG50 machine gun, but were unable to stop the ship.[25]

- 2009

- A wanted man cut a hole in the demilitarized zone fence and defected, but was later returned by North Korea.[17]

- 2019

- Choe In-guk, the son of former South Korean Foreign Minister Choe Deok-sin, said he had decided to "permanently resettle" in North Korea to honour his parents' wish that he live there and devote himself to the unification of the Korean peninsula, according to North Korea’s propaganda website Uriminzokkiri.[26]

List of notable defectors

- Choe Deok-sin, a South Korean foreign minister

- Ryu Mi-yong, the chairwoman of Chondoist Chongu Party and wife of Choe

- Kim Bong-han, a North Korean researcher of acupuncture

- Oh Kil-nam, a South Korean economist who later defected back to the South

- Shin Suk-ja, the wife of Oh Kil-nam, who was held together with their daughters as prisoners of conscience

- Ri Sung-gi, a North Korean chemist known both for his invention of vinalon, and possible involvement in nuclear weapons research

- Roy Chung (born Chung Ryeu-sup), the fifth U.S. Army defector to the North

- Li Fung-ryong a South Korean army officer who defected to the north in 1964

See also

- Americans in North Korea

- List of Western Bloc defectors, for other South Korean defectors who are not listed here

- North Korean defectors

References

- "Strangers At Home: North Koreans In The South" (PDF). International Crisis Group. 14 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Friedman, Herbert A. (5 January 2006). "Communist Korean War Leaflets". www.psywarrior.com. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1310&dat=19531025&id=lh1WAAAAIBAJ&sjid=t-IDAAAAIBAJ&pg=1692,3690157

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2209&dat=19850219&id=EYZKAAAAIBAJ&sjid=IpQMAAAAIBAJ&pg=3695,3111707

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19880216&id=GP5NAAAAIBAJ&sjid=0osDAAAAIBAJ&pg=1399,2786555

- Joe Ritchie (13 September 1979). "South Korean, Who Joined U.S. Army, Reportedly Defected to North Korea". Washington Post.

- "North Korea Is Promising No Harm And Cash Rewards For Defectors Who Come Back". Business Insider. 18 August 2013.

- "Why Do People Keep "Re-Defecting" To North Korea?". NK News - North Korea News. 11 November 2012.

- "Phenomenon of North Korean "double defectors" shows deepening divide". Scottish News - News in Scotland - Scottish Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012.

- Adam Taylor (9 August 2012). "Some North Korean Refugees Are So Depressed By Their Life In The South That They Go Back North". Business Insider.

- Adam Taylor (26 December 2013). "Why North Korean Defectors Keep Returning Home". Business Insider.

- Justin McCurry. "The defector who wants to go back to North Korea". the Guardian.

- "South Korea bans North Korean defector from repatriation - UPI.com". UPI. 22 September 2015.

- Will Ripley, CNN (23 September 2015). "Defector wants to return to North Korea". CNN.

- "A North Korean Defector’s Regret". The New York Times. 16 August 2015.

- Tim Hume, CNN (28 October 2013). "South Korea intrigued by 6 who defected to Pyongyang - CNN.com". CNN.

- "North Korea Returns South Korean 'Defectors'". VOA.

- Adam Withnall (28 October 2013). "South Korean defectors flee TO North Korea 'in search of better life' - but end up in detention for up to 45 months". The Independent.

- https://datosmacro.expansion.com/demografia/migracion/inmigracion/corea-del-norte

- "South Korean army shoots dead 'defector'". Telegraph.co.uk. 16 September 2013.

- "Choi Duk Shin, 75, Ex-South Korean Envoy". The New York Times. Associated Press. 19 November 1989. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/56241.stm

- http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2009/10/29/2009102900521.html

- http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2004/11/18/2004111861039.html

- http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2005/04/13/2005041361012.html?related_all

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/08/son-of-high-profile-south-korean-defector-moves-to-north-korea