Propaganda in South Korea

Propaganda in South Korea counters the extensive propaganda of rival North Korea or influence domestic and foreign audiences. According to the French philosopher and author Jacques Ellul, propaganda exists as much in a democracy as in authoritarian regimes.[1] South Korea's democracy uses propaganda to further its national interests and objectives. Methods of propaganda dissemination involve means of modern media to include television, radio, cinema, print, and the internet.

Themes

Anti-communism

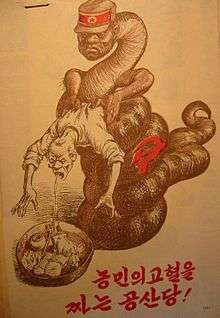

A national identity of anti-communism formed in South Korea under president Syngman Rhee after the nation’s inception in 1948. Strong anti-communist propaganda themes were created to counter North Korean communism and subversion which was seen as the threat.[2] The South Korean government enacted legislation against “anti-national” activities in 1948 and firmly establishing an anti-communist ideology with the National Security Act. The act outlawed any dissent or criticism of the ruling South Korean government, effectively making communism illegal. This included the media, art, literature and music. South Korea sought to establish itself as distinctly democratic and opposed to North Korea's communist national identity. This external theme was to lobby for the support of the United States for South Korea’s security. South Korean propaganda needed to counter the heavy pro-communist propaganda of North Korea and the cult of personality surrounding Kim Il-Sung. The competing propaganda themes sought to draw defectors to their respective ideologies in hopes of reuniting the peninsula. The anti-communist mindset was more firmly entrenched after the Korean War furthering animosity and the split between the two Koreas.[3]

Korean War

Propaganda was an important tool of war for South Korea in defending against the North Korean invasion and its propaganda attacks. The anti-communist ideology was firmly set and used to reinforce the South Korean national identity. The south needed to mobilize its own populace to survive and fight in a total war. According to the political scientist and author, Harold D. Lasswell in his study of World War I propaganda, nations at war demonize their enemy to reinforce the support of the populace and allies.[4] Demonizing propaganda sought to “fortify the mind of the nation with examples of the insolence and depravity of the enemy.”[5] Propaganda directed at North Korea was as vitriolic as the themes directed at South Korea. South Korean propaganda exploited the fact that the north launched the unprovoked invasion and often stalled negotiations for a ceasefire.[6][7]

Economic prosperity

South Korea worked to rebuild after the devastation of the Korean War. Propaganda worked to reinforce the ideology of the people working together to rebuild. Propaganda themes of economic prosperity were also to show South Korea as superior to North Korea and counter its anti-capitalist themes. Several economic reforms were enacted under president Park Chung-Hee from the 1960s and 1970s that were credited with South Korea’s current economic success. South Korea now ranks 15th among world economies rising from third world status after the war.[8] The New Village Movement or Saemaul Movement beginning in 1970 was considered an ideological movement directed by the Park government to the South Korean people to motivate them toward development.[9] President Park praises his economic achievements as an example for other countries in his self-laudatory book, “To Build a Nation.” In the book, Park describes his economic plans and the statistical results borne from developmental reforms.[10] The difference in economic development between North and South Korea was evident by the early 1970s. The challenges of the economic theme was revealing the growing quality of life in the south to the North Korean people and subvert the Kim Il-Sung regime. During the first bilateral talks between the two countries since the end of the war, the North Korean delegation was brought into the South Korean capital of Seoul. Seeing the rebuilt city and the bustling traffic in it, the leader of the North Korean delegation said, “We’re not stupid, you know. It’s obvious you’ve ordered all the cars in the country to be brought into Seoul to fool us.”. Lee Bum-suk, the chief representative of the South Korean delegation, replied, “Well, you’ve rumbled that one, but that was the easy part. The hard bit was moving in all the buildings.”.[11] The propaganda rivalry using the theme of South Korean prosperity versus the failed ideology of the north manifests itself today. South Korea renewed projecting propaganda across the Demilitarized Zone (Korea) in response to North Korean attacks in 2010. Loudspeakers and radio messages included Korean Popular music, or K-Pop, flaunting ideas of free will and prosperity.[12]

Ethno-nationalist pride

A strong Korean national identity based on ethnic pride has always been a part of Korean culture. The Imperial Japanese used ethno-nationalist propaganda themes during the occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945. It then served to maintain Korean subservience convincing them that the Japanese and Korean peoples are one, morally pure race.[13] Techniques used by the Japanese were adopted by both north and south after liberation in 1945. South Korean reinforcing propaganda continued to use ethno-nationalist themes of “koreanness,” to hold the support of the people.[14]

Reunification

South Korean ethno-nationalist propaganda would be used to reconcile with the north. Narratives appealing to common race and common ethnic identity is hoped to improve relations with the north and lead toward reunification.[15] The South Korean Sunshine Policy from 1998 to 2008 used such propaganda themes to increase contact and cooperation between north and south.[16]

Legacy of the Japanese occupation

South Korean propaganda is often projected toward Japan in a persistent island dispute off the peninsula’s east coast. Known as Dokdo in Korea or Takeshima in Japan, the disputed island is the subject of a propaganda war between South Korea and Japan. A greater propaganda war is the Comfort Women issue which, after decades of attempt to resolve since the 1990s, culminated in an Agreement between South Korea and Japan in 2015 that permanently settled the issue. However, despite Japan having fulfilled it's part of the agreement with compensation and a Prime Ministerial apology, in 2018 the South Korean government under President Moon Jae-In reneged on the agreement. [17][18]

Relations with the United States

The United States remains a key ally to South Korea and keeps a military presence to deter a second Korean War.[19] Younger generations of South Koreans without memory of the war or poverty in its aftermath look upon the US role and continued military presence unfavorably.[20] Governmental relations remain strong while polls of South Koreans show more unfavorable views of the US while favorable views of North Korea improved.[21] This changed significantly in 2010 after a series of attacks by North Korea including the sinking of the South Korean navy frigate, ROKS Cheonan.[22]

Methods

Film

Popular South Korean films often show reunification themes with friendships or family ties across the north and south division. The film Joint Security Area (2000) was the highest grossing Korean film up to that time. The movie depicted a friendship between soldiers from the north and south along the DMZ.[23]

Radio

South Korea broadcasts radio messages toward North Korea with news and propaganda themes. The South Korean government reduced projecting propaganda through the Sunshine Policy years. Propaganda broadcasts resumed after the election of the hardline president Lee Myung-bak in 2008 and increased after violent attacks by North Korea in 2010.[24]

Newspapers

South Korea has a free press like other democratic nations. South Korean newspapers are a forum for criticisms and support for political ideas and the government. Media coverage frequently is focused on North Korea and prospects for reunification.[25] Sensitivity about the Tokdo island dispute is also a common propaganda theme covered in South Korean print media.[26]

Leaflets

Leaflets with propaganda themes are sent by balloon to North Korea in hopes of reaching the populace with information. South Korean leaflet activity may start and stop depending on the level of dialog between the two Koreas.[27] Anti-communist or anti-North Korea organizations, not necessarily the South Korean government, may deliver propaganda leaflets.[28]

Internet

Both North Korea and South Korea engage in a propaganda war on the internet. Hackers from both sides will attack and shut down each other's websites and direct propaganda messages through social networks.[29]

See also

- Bias in reporting on North Korea

- Lee Seung-bok

References

- Ellul, Jacques (1973). Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes. Translated by Konrad Kellen; Jean Lerner (Repr. ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 232–242. ISBN 0-394-71874-7.

- Oh, Il-Whan (September 2011). "Anticommunism and the National Identity of Korea in the Contemporary Era: With a Special Focus on the USAMGIK and Syngman Rhee Government Periods". The Review of Korean Studies. 14 (3): 62–64, 72–78.

- Oh (2011), pp. 80-82.

- Lasswell, [by] Harold D. (1971). Propaganda technique in World War I. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press. pp. 77–101. ISBN 0-262-62018-9.

- Lasswell, Harold D. (1927), pg. 77.

- Stokesbury, James L. (1990). A short history of the Korean War. New York: Quill. pp. 33–49, 143–153. ISBN 0-688-09513-5.

- Joy, C. Turner (1955). How Communists Negotiate. New York: Macmillan. pp. 39–61.

- Nominal GDP list of countries for the year 2010, World Economic Outlook Database, November 2011, International Monetary Fund, accessed on 3 November 2011.

- Breen, Michael (1999). The Koreans : who they are, what they want, where their future lies (1st U.S. ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 133–142. ISBN 0-312-24211-5.

- Park, Chung-Hee (1971). To Build a Nation. Washington, DC: Acropolis Books. pp. 101–124, 170–196.

- Breen, Michael (1999), pg. 137.

- Jiminez, Justin (June 7, 2010). "A Brief History of South Korean Propaganda Blasts". Time.

- Myers, B.R. (2010). The cleanest race : how North Koreans see themselves and why it matters (1st ed.). Brooklyn, N.Y.: Melville House. pp. 25–29. ISBN 978-1-933633-91-6.

- Shin, Gi-wook (August 2, 2006). "Korea's ethnic pride source of prejudice, discrimination: Blood-based ethnic national identity has hindered cultural and social diversity, experts say". The Korea Herald.

- Shin, Gi-wook (August 2, 2006). "Korea's ethnic pride source of prejudice, discrimination: Blood-based ethnic national identity has hindered cultural and social diversity, experts say". The Korea Herald.

- Myers, B.R. (2010), pp. 55-60.

- "ROK Editorial: Dokdo is Ours". JoongAng Ilbo (Internet Version-WWW). July 15, 2008.

- Oh, Seok-min (August 3, 2011). "Dokdo ferry operator imposes ban on Japanese passengers". Yonhap News.

- U.S. Forces Korea home page, USFK, retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "(Korean War) Sixty Years On, Memories of War Fade, National Loyalty Falters in Affluent South". Yonhap News. June 20, 2010.

- Kim, Chi-ho (April 11, 2003). "ROK Poll: 41 Percent Dislike US, 46.1 Percent Call DPRK Partner of Cooperation". The Korea Herald (Internet Version-WWW) English Version.

- "North Korean torpedo sank Cheonan, South Korea military source claims: President Lee Myung-bak told military intelligence confirms sinking of navy corvette by North Korean submarine". The Guardian. April 22, 2010.

- J.S.A.: Joint Security Area on IMDb Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- "Seoul to Crank Up DMZ Propaganda". JoongAhg Daily. October 6, 2010.

- Kim, Young-jin (November 17, 2011). "ROK Daily: 'Seoul Not Intending to Absorb NK'". The Korea Times Online.

- "ROK Editorial: Tokdo is Ours". JoongAng Ilbo (Internet Version-WWW). July 15, 2008.

- "S. Korea Halts Sending Propaganda Leaflets to N. Korea". Yonhap News. November 15, 2011.

- Jiminez, Justin (June 7, 2010). "A Brief History of South Korean Propaganda Blasts". Time.

- Kim, Sam (January 10, 2011). "DPRK's Web Site Shuts Down After 'Apparent' Hacking by ROK Citizens". Yonhap News.

External links

- Korean War leaflets. Kirkwood Community College.

- South Korean Leaflets at the Wayback Machine (archived October 16, 2009). Matt Strum.