Sophienkirche

The Sophienkirche (Saint Sophia's Church) was a church in Dresden.

- For the churches of this name in Berlin and Bayreuth, see Sophienkirche (Berlin) and Sophienkirche (Bayreuth).

It was located on the northeast corner of the Postplatz (post office square) in the old town before it was severely damaged in the Dresden bombing in 1945 and subsequently destroyed in 1962 by the party and government of the GDR. It was the only Gothic church in the city.

History

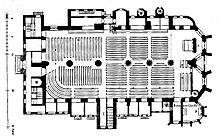

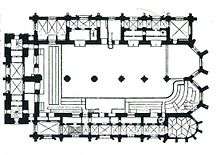

In 1250 The Order of Friars Minor, Franciscans, built a monastery and small church at the location of the future Sophienkirche — this was known as the Franziskanerkloster. Starting in 1331 the original structure was demolished and construction began of a larger church with two equally sized naves. Around 1400, at the southeast corner of the church, the Busmannkapelle was added, a private chapel for the patrician Busmann family to which the Dresden Mayor at the time, Lorenz Busmann, belonged and where he was later buried.

The Franciscan monastery was abolished during the Reformation.

Sophie of Brandenburg, Hofkirche

The Franciscan Friary stood empty for decades before it was restored in 1610 by Sophie of Brandenburg and reopened as a Lutheran church dedicated to Saint Sofia in her honour. In 1737 it became the (Evangelical Lutheran) Hofkirche (court church) of the Electorate of Saxony (not to be confused with the Roman Catholic Hofkirche the Elector began building at the same time).

Silbermann organ and Bach

Between the years 1718 and 1720 famed pipe organ maker Gottfried Silbermann installed one of the only 50 organs he completed, known for their clear meantone temperament. Johann Sebastian Bach is known to have played concerts on the instrument in 1725 and 1747.

The Kyrie and Gloria from Bach's B minor Mass were composed in 1733, possibly the former as a lament for the death of Elector Augustus II the Strong (who had died on 1 February 1733) and the latter to celebrate the accession of his successor the Saxon Elector and later King Augustus III of Poland, who converted to Catholicism in order to ascend the throne of Poland. In the hope of obtaining the title "Electoral Saxon Court Composer" Bach presented these to Augustus as a set of parts (Kyrie–Gloria Mass, BWV 232 I (early version)).[1][2] They may have been performed in 1733, not in the presence of its dedicatee, possibly at the Sophienkirche where Bach's son Wilhelm Friedemann Bach had been organist since June.[3] However, in 1734 Bach performed a secular cantata, a dramma per musica, BWV 215, in honour of Augustus, in the presence of the King and Queen, the first movement of which was later adapted into the B minor Mass Hosanna.[4]

The Sophienkirche up to 1945

The Sophienkirche was redesigned in the mid-19th century and took its final shape, with its twin neogothic spires (replacing the old Baroque tower), aisles and a new façade, between 1864–1868. After the German Revolution of 1918–19, the Sophienkirche ceased to serve as a court church and, seven years later, was made seat of the bishop of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Saxony.

In 1933 the towers were simplified (gothic elements were removed and the spires covered in copper) because they had been deteriorating and were becoming dangerous. This was intended as a temporary solution before restoring the neogothic details later.

1945, destruction and demolition

In the bombing of Dresden in February 1945 the Sophienkirche was gutted by fire and the Silbermann organ completely destroyed. The ceiling and walls remained intact until 1946 when the vaulted ceiling, without the support of the internal columns destroyed by the fire, collapsed leaving only the south spires standing. These were then intentionally destroyed in 1950 to recover the copper for the Kreuzkirche.

Gradually the ruins around the destroyed church were cleared. A reconstruction would have been quite possible but a comment by Walter Ulbricht, the party chief of the SED, "... a socialist city does not need Gothic churches", doomed the church.

Despite strong protests by Dresden conservators, architects and citizens, the remains of the church were destroyed in 1962 by resolution of the party and government of the German Democratic Republic.[5] Before that, the Nosseni and Sacristy altars had been salvaged, they can be seen now in the Loschwitzer Kirche (also in Dresden) and the Friedenskirche in Löbtau, respectively.

On 1 May 1963 the last parts of the oldest Dresden church disappeared — except for a partially destroyed sandstone framework of windows, which were stored in the catacombs under Brühl's Terrace.

Memorial

Beginning in 2009 a monument incorporating original fragments of the Busmann chapel has been built in the chapel's original position as a memorial to the Sophienkirche and a reminder of the horrors of war and the misuse of power by dictators. It is intended to enclose the memorial in a glass cube so that it can be used for exhibitions.[6]

References

- David, Hans T.; Mendel, Arthur (1945). The Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents. W. W. Norton & Co. p. 128.

- Wolff, Christoph (1998). The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents. W. W. Norton & Co Inc. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-393-04558-1.

- Wolff, Christoph. "Bach, III, 7 (§ 8)". In L.Macy (ed.). Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- David, Hans T.; Mendel, Arthur (1945). The Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents. W. W. Norton & Co. p. 132.

- Blaschke, K.; John, U.; Starke, H. (2006). Geschichte der Stadt Dresden. Geschichte der Stadt Dresden (in German). Theiss. p. 626. ISBN 978-3-8062-1928-9. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Die Busmannkapelle" (in German). Bürgerstiftung Dresden. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sophienkirche (Dresden). |