Sonning Cutting railway accident

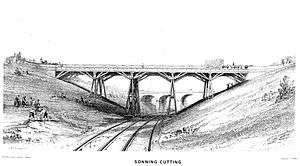

The Sonning Cutting railway accident occurred during the early hours of 24 December 1841 in the Sonning Cutting through Sonning Hill, near Reading, Berkshire. A Great Western Railway (GWR) luggage train travelling from London Paddington to Bristol Temple Meads station entered Sonning Cutting. The train was made up of the broad-gauge locomotive Hecla, a tender, three third-class passenger carriages, and some heavily-laden goods waggons. The passenger carriages were between the tender and the goods waggons.

| Sonning Cutting railway accident | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Date | 24 December 1841 ~06:50 am |

| Location | Sonning Cutting, Berkshire |

| Country | England |

| Line | Great Western Main Line |

| Cause | Line obstructed (landslip) |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Deaths | 9 |

| Injuries | 16 |

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |

Recent heavy rain had saturated the soil in the cutting causing it to slip, covering the line on which the train was travelling. On running into the slipped soil the engine was derailed, causing it to slow rapidly. The passenger coaches were crushed between the goods waggons and the tender. Eight passengers died at the scene and seventeen were injured seriously, one of whom died later in hospital.

Details of the accident and subsequent proceedings were reported widely by the newspapers of the day.

First reports

The first reports of the accident were published in The Times on Christmas Day, with the headline "Frightful Accident on the Great Western Railway".[1] Reporting was hindered by "strict reserve on the part of all the company's servants", but the account given in the newspaper could, according to The Times "be relied on as substantially correct".

The train left Paddington at about 4:30 am with about 38 passengers aboard "chiefly of the poorer class". Just before 7:00 am, in Sonning cutting, the train ran into soil that had slipped from the side of the cutting onto the track, covering it two or three feet deep. The engine and tender were derailed immediately and "the next truck, which contained the passengers, was thrown athwart the line, and in an instant was overwhelmed by the trucks behind, which were thrown into the air by the violence of the collision, and fell with fearful force upon it". Eight passengers were killed and sixteen others were "more or less severely wounded". After being extracted from the wreckage, the injured were taken to the Royal Berkshire Hospital at Reading, and the dead were carried to a hut near the site of the crash. Among the wounded were Thomas Martin Wheeler, a radical activist, and his wife.[2]

An inquest on those killed was opened at 3:00 pm on the same day, in a nearby public house, but The Times's correspondent could not obtain details of the evidence produced there. However, he wrote that, in the opinion of people living in the neighbourhood of the crash, the part of the cutting where the accident occurred was not secure; the cutting was deep, the sides were too steep and the soil through which it was cut was said to be of a "loose springy nature" that showed a tendency to slip. Bank-slips had occurred before in the cutting near to the crash site and these had been reported to the Great Western Railway. However, the GWR watchman responsible for this section of the line had reported that when examined at 5:00 pm on the day before the accident "there was not the slightest appearance of there being any danger of a slip taking place". Later it was determined that the slip must have occurred after 4:30 am, because this was the time that the "up" mail train passed through the cutting on its way to London.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, engineer of the GWR, on hearing of the crash left London with about one hundred workmen, in a special train, to clear the soils from the line.

The first inquest

The inquest on the victims who died at the scene of the accident was begun in the afternoon of the day of its occurrence, but then adjourned until the following Tuesday, 28 December 1841. The proceedings were held at the Shepherd's House Inn, which is near the scene of the accident. A jury of twelve men was sworn-in and the coroner began the inquest at 9.00 am. Those present included Charles Russell MP, chairman of the GWR, I.K. Brunel, engineer to the GWR and several other "influential gentlemen of the neighbourhood" including Mr R. Palmer MP, lord of the manor in which the crash happened.

The coroner stated that the object of the inquest was to hear evidence as to whether the earth slip that caused the accident had been sudden, or whether "it had occurred after a previous indication, which called-for and required the attention of the railway company...". Harrowing evidence on the identification of those killed was then heard: they were in the main stonemasons working in London who were returning home for Christmas.

The inquest then considered whether or not the bank slip that caused the accident might have been reasonably predicted. The first witness was a labourer who crossed a wooden bridge over the cutting twice a day and knew the spot where the slip happened. He had noticed bulging in the soils and a slip which had exposed drainage tiles at the same place, about two weeks before the accident happened. The witness did not know the distance between the wooden bridge and the slip, but the foreman of the jury said that it was about 270 yards (250 m). [Thus the accident occurred at about where indicated on the map shown on the right. The "wooden bridge" referred to crossed the cutting about 350-metres on the London side of the well-known brick bridge that carried the main Bath Road over the cutting.]

The next witness was a bricklayer who said that he knew the cutting well and that about two weeks before the accident he passed over the wooden bridge and on looking down the line towards Twyford he had noticed two slips nearly opposite each another, one on the right and the other on the left. The soils in the right hand slip, on the southern side of the line where the accident had happened, had fallen between the bank and the rails and amounted to one or two cart-loads and lay "in a sort of circle". The slip appeared to have occurred in the bank ten or twelve feet up from the bottom of the cutting. The witness estimated the distance between the wooden bridge and the site of the slip as being about 240 yards (220 m). Asked by the coroner if he saw anything else at the site of the slip, the witness replied that on the day in question he had seen two workmen shovelling soils back from the rails. Through the coroner, Brunel asked the witness whether he had seen drainage tiles near the spot, which he had not. When asked by a juror the witness said that the slip had not been made good, nor was it in the days that ensued. Brunel then asked the witness if he knew that slips were normally left open to drain them, but the witness said he knew nothing of this.

Other witnesses called confirmed having seen bulging and slips in the embankment near to the site of the accident. A GWR employee testified that between two and three weeks before the accident he had noticed a slip at the place where the accident happened. He and four men had drained the slip and a watch was kept on the works by night, because of the risk that further slippage might occur, but the watch was stopped after the slip had been made good.

Brunel in evidence then stated that he had examined the slip that caused the accident, but that it was a new one, close to the earlier one. The cutting was 57 feet (17 m) deep, 40 feet (12 m) wide at the bottom, 268 feet (82 m) wide at the top. Spoil heaps on the top edge of the slope had not moved and therefore could not have contributed to the slip. The passenger trucks on the train had been between the tender and the goods waggons because this was the safest place for them: "many accidents might arise to passengers if placed in the rear of the luggage trains" if a following train ran into it.

The coroner's jury returned a verdict of accidental death in all cases, and a deodand of one thousand pounds on the engine, tender, and carriages. The coroner refused to reveal the basis on which deodand had been made, but subsequently it emerged that firstly, "the jury are of opinion that great blame attached to the company in placing the passenger trucks so near the engine", and secondly "that great neglect had occurred in not employing a sufficient watch when it was most necessarily required".

The second inquest

One of those injured in the accident and moved to the Royal Berkshire Hospital died six days later. The inquest was held at Reading and the evidence heard was similar to that produced during the first inquest. Brunel added that in his opinion the derailment had been caused by a large stone, about two feet square, that had come down with the soils and that had been found where the engine left the line. In his opinion, "this fall of earth has taken place without previous symptoms". In reply to a question about the wisdom of placing the passenger trucks immediately behind the tender Brunel stated that this was the safest place because "there have been many instances of a train running into the luggage train on the Western Railway".

The jury returned a verdict of accidental death, but in their opinion the accident might have been avoided had there been a watch in the cutting. They therefore placed a deodand of one hundred pounds on the engine and its train and recommended that in future passenger trucks should be placed further away from the engine.

The deodands

At the two inquests, deodands of £1,100 (equivalent to £101,000 in 2019) in total were made on the engine (Hecla), and the trucks, payable to the lord of the manor of Sonning, Robert Palmer JP MP. Early reports suggested that Palmer intended to share the money between the injured and dependants of those killed, but this he denied, who believed it was very unlikely that the deodand payments would ever be made and that it would be unkind to raise false hopes amongst the potential beneficiaries. In the event, both deodands were overturned and the money was never paid.

Deodands, in effect penalties imposed on moving objects instrumental in causing death, were abolished about five years after the accident, with the passing of the Deodands Act 1846.

See also

- List of rail accidents in the United Kingdom

- Slope stability

- Mass wasting

References

- The Times. London. 25 December 1841. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Stevens, William (1862). A memoir of T. M. Wheeler. London: John Bedford Leno.

- Rolt, L. T. C. (1998). Red for Danger. Sutton.

- Lewis, Peter R (2007). Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847. Tempus.

- Lewis, Peter R; Nisbet, Alistair (2008). Wheels to Disaster!: The Oxford train wreck of Christmas Eve, 1874. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-4512-0.

External links

- Railways archive report on Sonning accident

- Large scale map of accident site from the Environment Agency's Magic Map. The accident occurred near to the small bite out of the top of the embankment to the north and west of Ryecroft Close. Right-click on the link and open it in a new tab or a new window.

- Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, 1844. On Railway Cuttings and Embankments. Provides an overview of knowledge existing on this subject at about the time of the accident. The accident at Sonning Cutting is discussed.

- Ibid. A section through the cutting at the scene of the accident.

- The Annual Register, 1842. Provides a short contemporaneous report of the accident.

- Legal report. On the overturning of the deodand ordered in respect of Richard Woolley, who was injured in the accident at Sonning but who died in Reading.

- The Mechanic's Magazine, January 1842. The Modern Mechanical Moloch. A letter concerning the accident.