Somali Bantus

The Somali Bantu (also called Jareerweyne, Jareer, Gosha, and Mushunguli) are a Bantu-speaking origin ethnic marginalized group(s) in Somalia who primarily reside in the southern part of the country, primarily near the Juba and Shabelle rivers. They are descendants of people from various Bantu ethnic groups, who were acquisitioned from Southeast Africa and in Somalia and other areas in Northeast Africa, and West Asia as part of the Arab slave trade.[3][4] Somali Bantus are not genetically related to the indigenous ethnic Somalis and have a culture which since their arrival in the country, has been distinct from the indigenous Somalis who are Cushitic and they have remained marginalized ever since their arrival in Somalia.[5]In 1991, 12,000 Bantu people were displaced into Kenya, and nearly 3,300 were estimated to have returned to Tanzania.[6]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 900,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southern Somalia | |

| Languages | |

| Mushunguli, Swahili, other Bantu languages, and Somali primarily the Maay dialect (through acculturation and ongoing language shift) | |

| Religion | |

| Primarily Islam[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bantu peoples, other Niger-Congo peoples |

There are six Somali Bantu Tribes: Magindo, Makua, Nyasa, Yao, Zalamo, Zigua. There are clans and sub-clans within these tribes. [6]

These Somali Bantu are not to be confused with the members of Swahili society in coastal towns, such as the Bajuni or the Bravanese, who speak dialects of the Swahili language but have a culture, tradition, and history separate of them.

All in all, the number of Bantu inhabitants in Somalia before the civil war is thought to have been about 80,000 (1970 estimate), with most concentrated between the Juba and Shabelle rivers in the south.[7] However, recent estimates place the figure as high as 900,000 persons.[1]

Etymology

The term "Somali Bantu" is an ethnonym that was invented by humanitarian aid-supplying agencies shortly after the outbreak of the civil war in Somalia in 1991. Its purpose was to help the staff of these aid agencies better distinguish between, on the one hand, Bantu minority groups hailing from Somalia and thus in need of immediate humanitarian attention and on the other hand, other Bantu groups from elsewhere in Africa that did not require immediate humanitarian assistance. The neologism further spread through the media, which repeated verbatim what the aid agencies' increasingly began indicating in their reports as the new name for Somalia's ethnically Bantu minorities. Prior to the civil war, the Bantu were simply referred to in the literature as Bantu, Gosha, Mushunguli or Jareer, (which is seen as an offensive/derogatory word against them) as they still, in fact, are within Somalia proper.[8]

History

Origin

Between 2500–3000 years ago, speakers of the original proto-Bantu language group began a millennia-long series of migrations eastward from their original homeland in the general Nigeria and Cameroon area of West Africa.[9] This Bantu expansion first introduced Bantu peoples to central, southern and southeastern Africa, regions where they had previously been absent from.[10][11]

The Bantus inhabiting Somalia are descended from Bantu groups that had settled in Southeast Africa after the initial expansion from Nigeria/Cameroon, and whose members were later acquisitioned and sold into the Arab slave trade.[10]

Slave trade

The Indian Ocean slave trade was multi-directional and changed over time. To meet the demand for menial labor, black Africans from southeastern Africa bought by Somali slave traders were sold in cumulatively large numbers over the centuries to customers in Morocco, Libya, Somalia, Egypt, Arabia, the Persian Gulf, India, the Far East and the Indian Ocean islands.[3][4]

From 1800 to 1890, between 25,000–50,000 black African slaves are thought to have been sold from the slave market of Zanzibar to the Somali coast.[12] Most of the slaves were from the Majindo, Makua, Nyasa, Yao, Zalama, Zaramo and Zigua ethnic groups of Tanzania, Mozambique, and Malawi. Collectively, these Bantu groups are known as Mushunguli, which is a term taken from Mzigula, the Zigua tribe's word for "people" (the word holds multiple implied meanings including "worker", "foreigner", and "slave").[3]

Bantu slaves were made to work in plantations owned by Somalis along the Shebelle and Jubba rivers, harvesting lucrative cash crops such as grain and cotton.[13]

Colonialism and the end of slavery

Since the very end of the eighteen century, fugitive slaves from the Shebelle valley began to settle in the Jubba valley. By the late 1890s, when Italians and British occupied the Jubaland area, an estimated 35,000 former Bantu slaves were already settled there.

The Italian colonial administration abolished slavery in Somalia at the turn of the 20th century by decree of the King of Italy. Some Bantu groups, however, remained enslaved until the 1910s in the areas not totally dominated by the Italians, and continued to be despised and discriminated against by large parts of Somali society.[14] After World War I, many Somali Bantus, mainly the descendants of former slaves, became Catholics. They were principally concentrated in the Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi and Genale plantations.[15]

Indeed, in 1895, the first 45 Bantu slaves were freed by the Italian colonial authorities under the administration of the chartered Catholic company Filonardi. The former were later converted to Catholicism. Massive emancipation and conversion of slaves in Somalia[16] only began after the anti-slavery activist and explorer Luigi Robecchi Bricchetti informed the Italian public about the local slave trade and the indifferent attitude of the first Italian colonial government in Somalia toward it.[17]

The Bantus were also conscripted to forced labor on Italian-owned plantations since the Somalis themselves were averse to what they deemed menial labor,[18] and because the Italians viewed the Somalis as racially superior to the Bantu.[19][20]

While upholding the perception of Somalis as distinct from and superior to the European construct of "black Africans", both British and Italian colonial administrators placed the Jubba valley population in the latter category. Colonial discourse described the Jubba valley as occupied by a distinct group of inferior races, collectively identified as the WaGosha by the British and the WaGoscia by the Italians. Colonial authorities administratively distinguished the Gosha as an inferior social category, delineating a separate Gosha political district called Goshaland, and proposing a "native reserve" for the Gosha.[19]

Contemporary situation

Profile

Bantus simply refer to themselves as Bantu. Those who can trace their origins to Bantu groups in southeast Africa refer to themselves collectively as Shanbara, Shangama or Wagosha. Those who trace their origins to Bantu tribes inhabiting areas further south call themselves Zigula", "Makua", "Yao", "Nyassa", "Ngindo", "Nyamwezi", "Mwera" and other names, although the Somalis from Mogadishu called them with a discriminatory word all together "Mushunguli"'.[21] While some Bantus have adopted the Afro-Asiatic Somali language, speaking for the most part a Bantu version of the southern Somali dialect of Af-Maay Maay, a number still speak a dialect of their ancestral Bantu languages. These Bantu idioms belong to the separate Niger-Congo family, and include languages like Zigua and Mushunguli.[3]

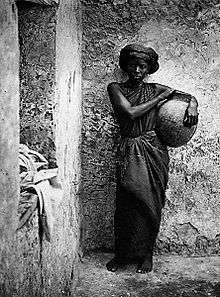

Unlike Somalis, most of whom are traditionally nomadic herders, Bantus are mainly sedentary subsistence farmers. The Bantus' predominant "Negroid" physical traits also serve to further distinguish them from Somalis. Among these phenotypic characteristics of the Bantu are kinky (jareer) hair, while Somalis are soft-haired (jilec).[22]

The majority of Bantus have converted to Islam, which they first began embracing in order to escape slavery.[23] Starting in the colonial period, some also began converting to Christianity.[24] However, whether Muslim or Christian, many Bantu have retained their ancestral animist traditions, including the practice of possession dances and the use of magic and curses.[23] Many of these religious traditions closely resemble those practised in Tanzania, similarities which also extend to hunting, harvesting and music, among other things.[10]

Many Bantu have also retained their ancestral social structures, with their Bantu tribe of origin in southeastern Africa serving as the principal form of social stratification. Smaller units of societal organization are divided according to matrilineal kinship groups,[25] the latter of which are often interchangeable with ceremonial dance groupings.[26][21] Meanwhile, they do maintain some traditions of their own, such as the common act of basket weaving. Another important cultural aspect of the Bantu people consists art using bright colors and fabrics.[27]

Primarily for security reasons, some Bantus have attempted to attach themselves to groups within the Somalis' indigenous patrilineal clan system of social stratification.[22] These Bantus are referred to by the Somalis as sheegato or sheegad (literally "pretenders"[28]), meaning they are not ethnically Somali and are attached to a Somali group on an adoptive, client basis. Bantus that have retained their ancestral southeast African traditions have likewise been known to level sarcasm at other Bantus who have tried to associate themselves with their Somali patrons, albeit without any real animosity (the civil war has actually served to strengthen relationships between the various Bantu sub-groups).[21][29][30]

All told, there has been very little co-mingling between Bantus and Somalis. Formal intermarriage is extremely rare, and typically results in ostracism the few times it does occur.[10][31]

Post-1991

During the Somali Civil War, many Bantu were forced from their lands in the lower Juba River valley, as militiamen from various Somali clans took control of the area.[32] Being visible minorities and possessing little in the way of firearms, the Bantu were particularly vulnerable to violence and looting by gun-toting militiamen.[10]

To escape war and famine, tens of thousands of Bantus fled to refugee camps like Dadaab in neighboring Kenya, with most vowing never to return to Somalia. In 1991, 12,000 Bantu people were displaced into Kenya, and nearly 3,300 were estimated to have returned to Tanzania.[6] In 2002, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) moved a large number of Bantu refugees 1500 km northwest to Kakuma because it was safer to process them for resettlement farther away from the Somali border.[3]

Resettlement in the United States

In 1999, the United States classified the Bantu refugees from Somalia as a priority and the United States Department of State first began what has been described as the most ambitious resettlement plan ever from Africa, with thousands of Bantus scheduled for resettlement in America.[33] In 2003, the first Bantu immigrants began to arrive in U.S. cities, and by 2007, around 13,000 had been resettled to cities throughout the United States with the help of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the U.S. State Department, and refugee resettlement agencies across the country.[33]

Among the resettlement destinations, it is known that Salt Lake City, Utah received about 1,000 Bantus. Other cities in the southwest such as Denver, Colorado, San Antonio, Texas, and Tucson, Arizona have received a few thousand as well. In New England, Manchester, New Hampshire and Burlington, Vermont were also destinations selected for resettlement of several hundred.[34] The documentary film Rain in a Dry Land chronicles this journey, with stories of Bantu refugees resettled in Springfield, Massachusetts and Atlanta, Georgia.[35] Plans to resettle the Bantu in smaller towns, such as Holyoke, Massachusetts and Cayce, South Carolina, were scrapped after local protests. There are also communities of several hundred to a thousand Bantu people in cities that also have high concentrations of ethnic Somalis such as the Minneapolis-St. Paul area,[36] Columbus, Ohio,[37] Atlanta,[38] San Diego,[39] Boston,[40] Pittsburgh,[41] and Seattle,[42] with a notable presence of about 1,000 Bantus in Lewiston, Maine.[43] Making Refuge follows Somali Bantus' strenuous journey towards eventual resettlement in Lewiston and details several families' stories of relocating there.[44]

Upon their resettlement in Lewiston, however, Bantus were met with a great amount of hostility from local Lewiston residents. In 2002, former Mayor Laurier Raymond wrote an open letter to Somali Bantu residents in an effort to dissuade them from further relocation to Lewiston.[45] He proclaimed their resettlement to the town had become a "burden"[46] on the community and predicted an overall negative impact on the town's social services and resources. In 2003, members of a white supremacist group demonstrated in support of the mayor's letter, which prompted a counter-demonstration of about 4,000 people at Bates College, as chronicled in documentary film The Letter. Despite such adversity, the Somali Bantu community in central Maine has continued to flourish and integrate in years since.[47][48]

Return to ancestral home

Prior to the United States' agreement to accommodate Bantu refugees from Somalia, attempts were made to resettle the refugees to their ancestral homes in southeastern Africa. Before the prospect of emigrating to America was raised, this was actually the preference of the Bantus themselves. In fact, many Bantus voluntarily left the UN camps where they were staying, to seek refuge in Tanzania. Such a return to their ancestral homeland represented the fulfillment of a two-century old dream.[33]

While Tanzania was initially willing to grant the Bantus asylum, the UNCHR did not provide any financial or logistical guarantees to support the resettlement and integration of the refugees into Tanzania. The Tanzanian authorities also experienced additional pressure when refugees from neighbouring Rwanda began pushing into the western part of the country, forcing them to retract their offer to accommodate the Bantus.[10][33] On the other hand, the Bantus who spoke kizigula had already started arriving in Tanzania since before the war due to discrimination experienced in Somalia.[49]

Mozambique, the other ancestral home of the Bantu, then emerged as an alternative point of resettlement. However, as it became clear that the United States was prepared to accommodate the Bantu refugees, the Mozambican government soon backed out on its promises, citing a lack of resources and potential political instability in the region where the Bantu might have been resettled.[33]

By the late 2000s, the situation in Tanzania had improved, and the Tanzanian government began granting Bantus citizenship and allocating them land in areas of Tanzania where their ancestors are known to have been taken from as slaves.[1][10][50]

See also

References

- "Tanzania accepts Somali Bantus". BBC News. 25 June 2003. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- https://somalibantumaine.org/somali-bantu-background/

- Refugee Reports, November 2002, Volume 23, Number 8

- Gwyn Campbell, The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, 1 edition, (Routledge: 2003), p.ix

- L. Randol Barker et al., Principles of Ambulatory Medicine, 7 edition, (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2006), p.633

- "Somali Bantu Refugees — EthnoMed". ethnomed.org. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, v.20, (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.: 1970), p.897

- Bantu ethnic identities in Somalia

- Philip J. Adler, Randall L. Pouwels, World Civilizations: To 1700 Volume 1 of World Civilizations, (Cengage Learning: 2007), p.169.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refugees Vol. 3, No. 128, 2002 UNHCR Publication Refugees about the Somali Bantu" (PDF). Unhcr.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Toyin Falola, Aribidesi Adisa Usman, Movements, borders, and identities in Africa, (University Rochester Press: 2009), p.4.

- "The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Henry Louis Gates, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1746

- David D. Laitin (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. University of Chicago Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-226-46791-7.

- Gresleri, G. Mogadiscio ed il Paese dei Somali: una identita negata. p.71

- Tripodi, Paolo. The Colonial Legacy in Somalia. p. 65

- History of Somali Bantu Archived 1 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Laitin, p.64.

- Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 120

- Francesca, Declich (2003). I Bantu della Somalia. Etnogenesi e rituali mviko. Milano: Franco Angeli.

- "The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture – People". Cal.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture – People: "Since many Bantu groups in pre-war Somalia wished to integrate into the dominant clan structure, identifying oneself as a Mushunguli was undesirable."

- "Somali Bantu – Religious Life". Cal.org. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- A History of the Expansion of Christianity (volume Vi) the Great Century in Northern Africa and Asia A.d. 1800-a.d. 1914, (Taylor & Francis), p.35.

- Declich, Francesca. "Borders and borderlands as Resources in the Horn of Africa". In Borders and Borderlands as Resources in the Horn of Africa (Feyissa, Dereje and Hoehne, Markus Virgil Ed.). Oxford: James and Currey: 169–186.

- Declich, Francesca (2005). "Identity, dance and islam among People with Bantu Origins in Riverine Areas of Somalia". In the Invention of Somalia (Ali Jimale Ed.): 191–222.

- "Somali Bantu Health Sheet". doi:10.1037/e547012011-001. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p.190.

- Horn of Africa: IRIN Update, 23 November – SOMALIA: Minority group to be resettled

- J. Abbink, Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden. Afrika-Studiecentrum, The total Somali clan genealogy: a preliminary sketch, (African Studies Centre: 1999)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "SOMALI BANTU – Their History and Culture". Cal.org. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Barnett, Don. "Out of Africa: Somali Bantu and the Paradigm Shift in Refugee Resettlement". Cis.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- https://wiki.colby.edu/display/AY298B/More+information+on+Community+and+Environment

- Anne Makepeace. "Rain in a Dry Land". Pbs.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "MTN News". Mtn.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Hampson, Rick (21 March 2006). "After 3 years, Somalis struggle to adjust to U.S". USA Today. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Washington, DC (6 June 2003). "Somali Bantus in Georgia – 2003-06-06 | News | English". Voanews.com. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "FAQ". Sbantucofsd.org. 5 March 2004. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "Somali Bantu refugees celebrate Mothers Day". Hiiraan.com. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "KIR - Lawrenceville". University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- "News From The Field". Theirc.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "About Us – The Somali Bantu Experience: From East Africa to Maine – Colby College Wiki". Wiki.colby.edu. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Besteman, Catherine (February 2016). Making Refuge: Somali Bantu Refugees and Lewiston, Maine. Duke University Press. pp. 1–376. ISBN 978-0-8223-6044-5.

- Powell, Michael. "In Maine Town, Sudden Diversity And Controversy". The Washington Post. 14 October 2002.

- Raymond, Laurier. "A Letter to the Somali Community". Immigration's Human Cost. 1 October 2002.

- SBCA Maine. "Somali Bantu Community Association".

- City of Lewiston. "Immigrant and Refugee Integration and Policy Development Working Group". December 2017.

- Declich, Franceca (2010). Can boundaries not border on one another? The Zigula (Somali Bantu) between Somalia and Tanzania. Oxford: James and Currey. pp. 169–186.

- "Somali Bantus gain Tanzanian citizenship in their ancestral land". Alertnet.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

External links

General:

- UNHCR Publication Refugees about the Somali Bantu

- The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture

- Differences That Matter: The Struggle of the Marginalised in Somalia

In the U.S.:

- The Somali Bantu Experience

- Refugees USA

- Somali Bantus Arrive In Salt Lake City

- Somali Bantu Community – Development Council of Denver