Slide whistle

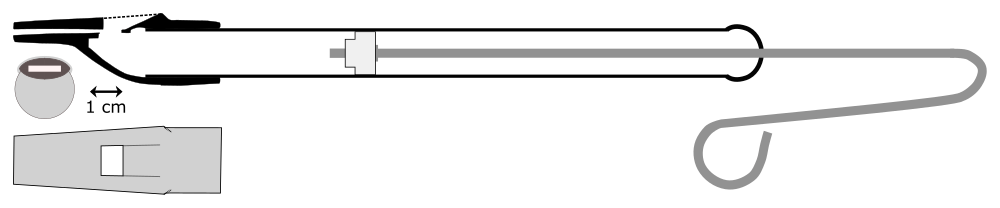

A slide whistle (variously known as a swanee or swannee whistle, lotos flute[1] piston flute, or jazz flute) is a wind instrument consisting of a fipple like a recorder's and a tube with a piston in it. Thus it has an air reed like some woodwinds, but varies the pitch with a slide. The construction is rather like a bicycle pump. Because the air column is cylindrical and open at one end and closed at the other, it overblows the third harmonic. "A whistle made out of a long tube with a slide at one end. An ascending and descending glissando is produced by moving the slide back and forth while blowing into the mouthpiece."[2] "Tubular whistle with a plunger unit in its column, approximately 12 inches long. The pitch is changed by moving the slide plunger in and out, producing ascending and descending glisses."[3] Hornbostel–Sachs number: 421.221.312.

History

Piston flutes, in folk versions usually made of cane or bamboo, existed in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific as well as Europe before the modern version was invented in England in the nineteenth century. The latter, which may be more precisely referred to as the slide or Swanee whistle, is commonly made of plastic or metal.[4]

The modern slide whistle is familiar as a sound effect (as in animated cartoon sound tracks, when a glissando can suggest something rapidly ascending or falling, or when a player hits a "Bankrupt" on Wheel of Fortune), but it is also possible to play melodies on a slide whistle.

The swanee whistle dates back at least to the 1840s, when it was manufactured by the Distin family and featured in their concerts in England. Early slide whistles were also made by the English J Stevens & Son and H A Ward. By the 1920s the slide whistle was common in the US, and was occasionally used in popular music and jazz as a special effect. For example, it was used on Paul Whiteman's early hit recording of Whispering (1920).[5] Even Louis Armstrong switched over from his more usual cornet to the slide whistle for a chorus on a couple of recordings with King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band,[6] such as Sobbin' Blues (1923).[7] At that time, slide saxophones, with reeds rather than a fipple, were also built. The whistle was also widely used in Jug band music of the 1920s such as Whistler's Jug Band. Gavin Gordon uses a slide whistle in his ballet The Rake's Progress (1935).[8]

Uses

The slide whistle is often thought of as a toy instrument, especially in the West, though it has been and still is used in various forms of "serious" music. Its first appearance in notated European classical music may have been when Maurice Ravel called for one in his opera L'enfant et les sortilèges.[4] More modern uses in classical music include Paul Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 1, op. 24 no. 1 (1922), Luciano Berio's Passaggio, which uses five, and the Violin Concerto of György Ligeti, as well as pieces by Cornelius Cardew, Alberto Ginastera, Hans Werner Henze, Peter Maxwell Davies, and Krzysztof Penderecki (De Natura Sonoris II, 1971[9]). John Cage's Music of Changes (1951) and Water Music (1952) both feature slide whistle and duck calls.[10] The slide whistle is also used in many of the works of P. D. Q. Bach.

In the 1930s through the 1950s it was played with great dexterity by Paul 'Hezzie' Trietsch, one of the founding members of the Hoosier Hot Shots. They made many recordings.

Bob Dylan played a siren whistle – a slide whistle that provides a siren-like sound – mounted in his harmonica holder, in his 1965 song Highway 61 Revisited. Reportedly, during the sessions, keyboardists Al Kooper would sneak up on anyone using illicit substances, and blow the whistle in imitation of a police siren. Dylan then incorporated the instrument into the song, which is credited as "police car."

Roger Waters played two notes on the slide whistle in the song Flaming, from Pink Floyd's debut album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

A more recent appearance of the slide whistle can be heard in the 1979 song Get Up by Vernon Burch. The slide whistle segment of this song was later sampled by Deee-Lite in their 1990 hit Groove Is in the Heart. Fred Schneider of The B-52s plays a plastic toy slide whistle in live performances of the song Party Out of Bounds as a prop for the song's drunken partygoer theme, in place of the trumpet thus used in the studio for the Wild Planet song.

See also

References

- Karl Peinkofer and Fritz Tannigel, Handbook of Percussion Instruments, (Mainz, Germany: Schott, 1976), 78.

- Adato, Joseph and Judy, George (1984). The Percussionist's Dictionary: Translations, Descriptions, and Photographs of Percussion Instruments from Around the World, p.32. Alfred Music. ISBN 9781457493829.

- Beck, John H. (2013). Encyclopedia of Percussion, p.83. Routledge. ISBN 9781317747680.

- Hugh Davies. "Swanee whistle." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/47634 (accessed October 10, 2009).

- Berrett, Joshua (2004). Louis Armstrong & Paul Whiteman: Two Kings of Jazz, p. 62. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10384-0.

- Louis Armstrong's discography: Early years - 1901 1925

- (1990). Jazz Journal International. Billboard.

- Anthony Baines; Adrian Boult (1967). Woodwind Instruments and Their History. Books.google.com. p. 35. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- Beck (2013), p. 29.

- Iddon, Martin (2013). John Cage and David Tudor: Correspondence on Interpretation and Performance, p. 91. Cambridge University. ISBN 9781107310889.