Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Regiment

Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Originally raised as Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Battalion, the unit consisted of men recruited in Missouri by Lieutenant Colonel Alonzo W. Slayback during Price's Raid in 1864. The battalion's first action was at the Battle of Pilot Knob on September 27; it later participated in actions at Sedalia, Lexington, and the Little Blue River. On October 22, the unit was used to find an alternate river crossing during the Battle of the Big Blue River. Slayback's unit then saw action at the Battle of Westport on October 23, the Battle of Marmiton River on October 25, and the Second Battle of Newtonia on October 28. The battalion was briefly furloughed in Arkansas before rejoining Major General Sterling Price in Texas in December. Probably around February 1865, the battalion reached official regimental strength after additional recruits were added to it.

| Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Regiment Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Battalion | |

|---|---|

| Active | Late 1864 to June 14, 1865 |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Cavalry |

| Engagements | American Civil War

|

On June 2, the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department surrendered. The men of the regiment were stationed at different points in Louisiana and Arkansas when they were paroled twelve days later, leading the historian James McGhee to believe that the regiment had disbanded before the surrender.

Background

At the outset of the American Civil War in 1861, the state of Missouri was a slave state. Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson supported secession, and activated pro-secession state militia. The militia were sent to the vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri, where Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon dispersed the group using Union Army troops in the Camp Jackson affair on May 10. A pro-secession riot in St. Louis followed, in which several military personnel and civilians were killed or wounded. On May 12, Jackson formed a pro-secession militia unit known as the Missouri State Guard and placed Major General[lower-alpha 1] Sterling Price in command. In June, Lyon moved against the state capital of Jefferson City and evicted Jackson and the pro-secession group of state legislators. Jackson's party moved to Boonville, although Lyon captured that city after the Battle of Boonville on June 17.[2]

In July, anti-secession state legislators held a vote rejecting secession. Brigadier General Ben McCulloch of the Confederate States Army joined Price's militia forces; the combined group defeated Lyon at the Battle of Wilson's Creek in southwestern Missouri on August 10.[3] After Wilson's Creek, Price drove northwards, capturing the city of Lexington. However, the Missouri State Guard retreated in the face of Union reinforcements, falling back to southwestern Missouri. In November, while at Neosho, Jackson and the pro-secession legislators voted to secede, and joined the Confederate States of America as a government-in-exile.[4] In February 1862, Price abandoned Missouri for Arkansas in the face of Union pressure, joining forces commanded by Major General Earl Van Dorn.[5] In March, Price officially joined the Confederate States Army, receiving a commission as a major general.[1] That same month, Van Dorn was defeated at the Battle of Pea Ridge, giving the Union control of Missouri.[6] By July 1862, most of the men of the Missouri State Guard had left to join Confederate States Army units.[7] Missouri was then plagued by guerrilla warfare throughout 1862 and 1863.[8]

Organization

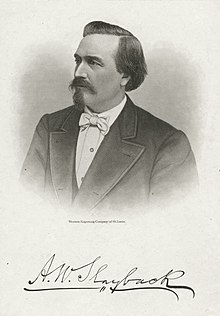

The origins of the Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Regiment began when Lieutenant Colonel Alonzo W. Slayback, a veteran of the Missouri State Guard, was authorized by Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby to recruit a regiment for the Confederate States Army on August 14, 1864. In September, Slayback entered Missouri and began recruiting as part of Price's Raid. Accompanying the brigade of Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke, Slayback was able to recruit a small group of men, which became part of Marmaduke's forces on September 23, while the men were at Zalma, Missouri.[9] The unit grew in strength over the course of Price's Raid, reaching battalion strength in October 1864. It was expanded to full regimental strength around February 1865.[10] By this point, Slayback was the regiment's colonel, Caleb W. Dorsey was lieutenant colonel,[lower-alpha 2], and John H. Guthrie was the regiment's major.[lower-alpha 3] At full strength, the regiment contained ten companies, all Missouri-raised, designated with the letters A–I and K.[9]

Service history

By the beginning of September 1864, events in the eastern United States, especially the Confederate defeat in the Atlanta campaign, gave Abraham Lincoln, who supported continuing the war, an edge in the 1864 United States Presidential Election over George B. McClellan, who promoted an end to the war. At this point, the Confederacy had very little chance of winning the war.[11] Meanwhile, in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Confederates had defeated Union attackers in the Red River campaign in Louisiana in March through May. As events east of the Mississippi River turned against the Confederates, General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, was ordered to transfer the infantry under his command to the fighting in the Eastern and Western Theaters. However, this proved to be impossible, as the Union Navy controlled the Mississippi River, preventing a large scale crossing. Despite having limited resources for an offensive, Smith decided that an attack designed to divert Union troops from the principal theaters of combat would have the same effect as the proposed transfer of troops. Price and Confederate Governor of Missouri Thomas Caute Reynolds suggested that an invasion into Missouri would be an effective offensive; Smith approved the plan and appointed Price to command the offensive. Price expected that the offensive would create a popular uprising against Union control of Missouri, divert Union troops away from principal theaters of combat (many of the Union troops defending Missouri had been transferred out of the state, leaving the Missouri State Militia to be the state's primary defensive force), and aid McClellan's chance of defeating Lincoln;[12] on September 19, Price's column entered the state.[13]

On September 27, 1864, Slayback's unit made a minor assault against the defenses of Fort Davidson during the Battle of Pilot Knob; the unit suffered light casualties.[9] That night, Slayback sent a note to the Union garrison commander Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr. suggesting that Ewing's African American soldiers would be massacred in events similar to the Fort Pillow Massacre if the fort fell.[14] Slayback's unit was then positioned north of the fort in order to detect any potential Union movement.[15] That night, the Union garrison retreated without being detected by Slayback's force and blew up the fort's magazine.[16] On October 2, while stationed at Union, Missouri, Slayback's unit, now known as Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Battalion, was assigned to Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson's[lower-alpha 4] brigade of Shelby's division.[18] While the Confederates were moving through Missouri, a Union force was reported to have left Jefferson City; Slayback's battalion was detached on October 13 to scout the approach of this force.[19] By the next day, Slayback's battalion had reached Longwood, where it was joined by other Confederate units.[20]

On October 15, Slayback's battalion, along with Collins' Missouri Battery, the 5th Missouri Cavalry Regiment, and Elliott's Missouri Cavalry Regiment, raided the town of Sedalia under Thompson's command. A Union garrison defended small fortifications, but a cavalry charge quickly overran the positions. After Collins' artillery opened fired, the remaining defenders were completely dispersed; the town was then looted.[21] Slayback's unit performed guard duty after the fighting,[10] as it was in a better state of organization than the other regiments that had participated in the skirmish.[22] The battalion next fought at the Second Battle of Lexington on October 19, in which the unit attacked and defeated a Union force. On October 21, the battalion was part of a Confederate force that forced a crossing of the Little Blue River.[10] On October 22, during the Battle of the Big Blue River, Shelby ordered the 5th Missouri Cavalry and Slayback's battalion to search for a secondary crossing of the river, as Byram's Ford, the primary crossing, was strongly defended.[23] Slayback's battalion quickly found an alternate ford, and crossed the river, hitting Colonel Charles R. Jennison's brigade in the flank. Jennison's brigade scattered, but the Union line was able to reform.[24] Later that day, the Confederates again moved against the Union position, with Slayback himself in the lead. However, the Union forces withdrew before any action occurred.[25]

At the Battle of Westport on October 23, Slayback's battalion was pressed by a Union attack. Shelby then ordered Thompson's brigade to charge, and the cavalrymen, including Slayback's battalion, were soon engaged in a melee. However, the Confederate forces were forced to fall back in a state that Shelby described as "weak and staggering".[26] Slayback's battalion then retreated 2 miles (3.2 km) to a stone fence, where it rallied. The defense held, and Union forces fell back, allowing Shelby to retreat from the field.[26] The unit next fought at the Battle of Marmiton River on October 25.[27] An initial Confederate stand was successful, but another Union charge was made. After 15 minutes of fighting, the Confederate line, including Slayback's unit, "melted away". Shelby reported that fatigue was an element in the defeat.[28] At the Second Battle of Newtonia on October 28, Slayback's battalion fought dismounted as the leftmost unit of Thompson's brigade.[29][30] Thompson then attacked and gained some ground, but was halted by fire from Union mountain howitzers. After a repositioning of the Union line, the Confederates pressed the attack farther, gaining more ground. However, Union reinforcements commanded by Brigadier General John B. Sanborn stabilized the line and then charged. Shelby withdrew due to the arrival of the fresh Union troops.[31]

After the defeat at Newtonia, Price's Army of Missouri retreated to Arkansas, where Slayback's unit was furloughed. The unit, by then 300 men strong, rejoined Price in Texas in December. Probably around February 1865, Slayback's command was combined with a group of recruits commanded by Dorsey, creating a full regiment of ten companies.[18] On June 2, General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department.[32] When the men of the regiment were paroled on June 14, 1865, part of the unit was located at Shreveport, Louisiana, while another part was at Wittsburg, Arkansas. Historian James McGhee interpreted this arrangement as suggesting that the regiment was disbanded before the surrender. Any specific casualties suffered by the unit are unknown, as Slayback did not issue casualty reports.[33] One source claimed that the regiment was issued lances instead of firearms, although that claim is likely inaccurate.[10][34]

Notes

References

- Wright 2013, p. 480.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 19–20.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 20–21.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 23–25.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–35.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–37.

- Gottschalk 1991, p. 120.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 377–379.

- McGhee 2008, p. 131.

- McGhee 2008, p. 132.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 343.

- Collins 2016, pp. 27–28.

- Collins 2016, p. 37.

- Busch 2010, p. 31.

- Busch 2010, p. 32.

- Busch 2010, pp. 33–34.

- Warner 1987, p. xviii.

- McGhee 2008, pp. 131–132.

- Official Records 1893, p. 664.

- Official Records 1893, pp. 664–665.

- Jenkins 1906, pp. 52–53.

- Official Records 1893, p. 665.

- Monnett 1995, pp. 77–79.

- Monnett 1995, pp. 80–81.

- Official Records 1893, p. 667.

- Official Records 1893, pp. 658–659, 662.

- Collins 2016, p. 163.

- Official Records 1893, pp. 659–660.

- Collins 2016, pp. 174–175.

- Wood 2010, p. 122.

- Collins 2016, pp. 177, 179.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 438.

- McGhee 2008, pp. 132–133.

- Sellmeyer 2007, p. 276.

Sources

- Busch, Walter E. (2010). Fort Davidson and the Battle of Pilot Knob. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-023-2.

- Collins, Charles D., Jr. (2016). Battlefield Atlas of Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-940804-27-9.

- Gottschalk, Phil (1991). In Deadly Earnest: The Missouri Brigade. Columbia, Missouri: Missouri River Press. ISBN 978-0-9631136-1-0.

- Jenkins, Paul Burrill (1906). The Battle of Westport (PDF). Kansas City, Missouri: Franklin Hudson Publishing Company. OCLC 711047091.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- McGhee, James E. (2008). Guide to Missouri Confederate Regiments, 1861–1865. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-870-7.

- Monnett, Howard N. (1995) [1964]. Action Before Westport 1864 (Revised ed.). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-413-6.

- Sellmeyer, Deryl P. (2007). Jo Shelby's Iron Brigade. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican. ISBN 978-1-58980-430-2.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 41. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1893. OCLC 262466842.

- Warner, Ezra J. (1987) [1959]. Generals in Gray (Louisiana Paperback ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3150-3.

- Wood, Larry (2010). The Two Civil War Battles of Newtonia. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 1-59629-857-X.

- Wright, John D. (2013). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Civil War Biographies. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87803-6.