Slavery in Ireland

Slavery had already existed in Ireland for centuries by the time the Vikings began to establish their coastal settlements, but it was under the Norse-Gael Kingdom of Dublin that it reached its peak, in the 11th century.[1]

History

Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic raiders kidnapped and enslaved people from across the Irish Sea for two centuries after the Fall of the Western Roman Empire destabilised Roman Britain; their most famous victim was Saint Patrick.[2]

The Brehon Laws Senchus Mór [Shanahus More] and the Book of Acaill [Ack'ill].a daer fuidhir was a name applied to all who did not belong to a clan, whether born in the territory or not. This was the lowest of the three classes of the non-free people. This class also was sub-divided into saer and doer, the daer fuidhirs being the class most closely resembling slaves. Even this lowest condition was not utterly hopeless; progress and promotion were possible, and indeed were in constant operation. In other ways also the law discouraged the introduction of fuidhirs; and when they had been introduced it favoured and facilitated the well-being and emanci-pation of such of them as were not criminal. Therefore all families did not remain permanently in this kind of servitude but gradually rose from a lower to a higher degree according to a certain scale of progress, unless they committed some crime which would arrest that progress and cast them down again.[3]

Viking period

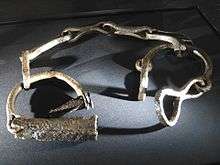

From the 9th to the 12th century Viking/Norse-Gael Dublin in particular was a major slave trading center which led to an increase in slavery.[4] In 870, Vikings, most likely led by Olaf the White and Ivar the Boneless, besieged and captured the stronghold of Dumbarton Castle (Alt Clut), the capital of the Kingdom of Strathclyde in Scotland, and the next year took most of the site's inhabitants to the Dublin slave markets.[4]

When the Vikings established early Scandinavian Dublin in 841, they began a slave market that would come to sell thralls captured both in Ireland and other countries as distant as Spain,[5] as well as sending Irish slaves as far away as Iceland,[6] where Gaels formed 40% of the founding population,[7] and Anatolia.[8] In 875, Irish slaves in Iceland launched Europe's largest slave rebellion since the end of the Roman Empire, when Hjörleifr Hróðmarsson's slaves killed him and fled to Vestmannaeyjar. Almost all recorded slave raids in this period took place in Leinster and southeast Ulster; while there was almost certainly similar activity in the south and west, only one raid from the Hebrides on the Aran Islands is recorded.[9]

Slavery became more widespread in Ireland throughout the 11th century, as Dublin became the biggest slave market in Western Europe.[9][5] Its main sources of supply were the Irish hinterland, Wales and Scotland.[9] The Irish slave trade began to decline after William the Conqueror consolidated control of the English and Welsh coasts around 1080, and was dealt a severe blow when the Kingdom of England, one of its biggest markets, banned slavery[10] in its territory in 1102.[6][9] The continued existence of the trade was used as one justification for the Norman conquest of Ireland after 1169, after which the Hiberno-Normans replaced slavery with feudalism.[6][11] The 1171 Council of Armagh freed all Englishmen and -women kept as slaves in Ireland.[12] It was clear from the Decree of the Council of Armagh that English were selling their children as slaves. "For the English people hitherto throughout the whole of their kingdom to the common injury of their people, had become accustomed to selling their sons and relatives in Ireland, to expose their children for sale as slaves, rather than suffer any need or want."[13]

Atlantic slave trade

It is believed the Irish people were involved with the Atlantic slave trade in Black African slaves between 1660 and 1815. For example, William Ronan, worked for the Royal African Company and rose to become chairman of the committee of merchants at Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), running one of the world's largest slave markets between 1687 and 1697.[14] Antoine Walsh, of Anglo-Norman Ancestry, a prominent Jacobite based in Nantes, used his wealth generated from the slave trade to finance the Jacobite rising of 1745.[15] Benjamin McMahon worked for eighteen years as an overseer on Jamaican plantations, later becoming an abolitionist and writing about his experiences.[16] Anglo-Norman descendants living in Ireland got involved with the slave trade in Liverpool, including Tralee native David Tuohy.[17] Librarian Liam Hogan[18] has described how Irish merchants profited from the trade, mostly indirectly as provisioners. However, the Irish had rights that the black African slaves did not, and, were considered human, not property.

Modern day

The US Department of State criticised Ireland in 2018 for "not meeting the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking"; types of modern slavery and forced labour include prostitution, trawler fishing and domestic service.[19][20]

References

- Dickson, David (2014). Dublin: The Making of a Capital City. Harvard University Press. p. 10. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- Medieval Ireland (2005): An Encyclopedia, Ed. Sean Duffy, 2017, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 1351666177, 9781351666176

- "Ginnell, Laurence, (1854–17 April 1923), MP N Westmeath, 1906–18, Westmeath Co., since 1918; Barrister, Middle Temple, 1893 and also of King's Inns, Dublin, 1906", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2007-12-01, retrieved 2020-01-27

- The Historical encyclopedia of world slavery, Volume 1; Volume 7 By Junius P. Rodriguez ABC-CLIO, 1997

- "The Slave Market of Dublin". 23 April 2013.

- "The Viking slave trade: entrepreneurs or heathen slavers?". 5 March 2013.

- "The Arctic Irish: fact or fiction?". 1 March 2013.

- "Medieval Irish merchants traded in slaves in Tunisia and Iceland". 2 August 2016.

- http://static.sdu.dk/mediafiles//Files/Om_SDU/Institutter/Ihks/Forskningsenheder/CMRS/Materials/Holmslavetrade.pdf

- Dickson, David (2014). Dublin The Making of a Capital City. Profile Books Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-674-74444-8.

- Rodgers, N. (31 January 2007). "Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery: 1612-1865". Springer – via Google Books.

- https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/1171latrsale.asp

- "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". sourcebooks.fordham.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- O'Shea, Joe (4 October 2012). "Murder, Mutiny & Mayhem: The Blackest-Hearted Villains from Irish History". The O'Brien Press – via Google Books.

- "The Irish and the Atlantic slave trade". 28 February 2013.

- Higman, B. W. (March 20, 1995). "Slave Population and Economy in Jamaica, 1807-1834". Press, University of the West Indies – via Google Books.

- "The Tuohy papers". British Online Archives.

- "Liam Hogan – Humanities Commons". Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- Pollak, Sorcha. "State criticised by US over inaction on modern slavery". The Irish Times.

- Hennessy, Michelle. "'A wake-up call': There are 800 people living in modern slavery in Ireland". TheJournal.ie.

Further reading

- Holm, P (1986). "The Slave Trade of Dublin, Ninth to Twelfth Centuries". Peritia. 5: 317–345. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.139. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Wyatt, D (2009). Slaves and Warriors in Medieval Britain and Ireland, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 45). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17533-4. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Wyatt, D (2014). "Slavery, Power and Cultural Identity in the Irish Sea Region, 1066–1171". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 65). Leiden: Brill. pp. 97–108. ISBN 978-90-04-25512-8. ISSN 1569-1462.