Sigrdrífumál

Sigrdrífumál (also known as Brynhildarljóð[1]) is the conventional title given to a section of the Poetic Edda text in Codex Regius.

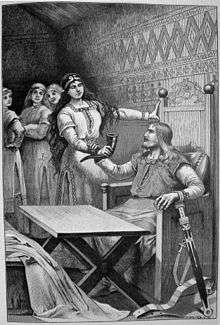

It follows Fáfnismál without interruption, and it relates the meeting of Sigurðr with the valkyrie Brynhildr, here identified as Sigrdrífa ("driver to victory").[2] Its content consists mostly of verses concerned with runic magic and general wisdom literature, presented as advice given by Sigrdrifa to Sigurd. The metre is fornyrðislag, except for the first stanza.

The end is in the lost part of the manuscript but it has been substituted from younger paper manuscripts. The Völsunga saga describes the scene and contains some of the poem.

Name

The compound sigr-drífa means "driver to victory"[2] (or "victory-urger", "inciter to victory"[3]) It occurs only in Fafnismal (stanza 44) and in stanza 4 of the Sigrdrifumal. In Fafnismal, it could be a common noun, a synonym of valkyrie, while in Sigrdrifumal it is explicitly used as the name of the valkyrie whose name is given as Hildr or Brynhildr in the Prose Edda.[2] Bellows (1936) emphasizes that sigrdrifa is an epithet of Brynhildr (and not a "second Valkyrie").[4]

Contents

The Sigrdrifumal follows the Fafnismal without break, and editors are not unanimous in where they set the title. Its state of preservation is the most chaotic in the Eddaic collection. Its end has been lost in the Great Lacuna of the Codex Regius. The text is cut off after the first line of stanza 29, but this stanza has been completed, and eight others have been added, on the evidence of the much later testimony of paper manuscripts.

The poem appears to be a compilation of originally unrelated poems. However, this state of the poem appears to have been available to the author of the Volsungasaga, which cites from eighteen of its stanzas.

The basis of the text appears to be a poem dealing with Sigurth's finding of Brynhild, but only five stanzas (2-4, 20-21) deal with this narrative directly. Stanza 1 is probably taken from another poem about Sigurd and Brynhild. Many critics have argued that it is taken from the same original poem as stanzas 6-10 of Helreid Brynhildar.

In stanzas 6-12, Brynhild teaches Sigurth the magic use of the runes. To this has been added similar passages on rune-lore from unrelated sources, stanzas 5 and 13-19. This passage is the most prolific source about historical runic magic which has been preserved.

Finally, beginning with stanza 22 and running until the end of the preserved text is a set of counsels comparable to those in Loddfafnismal. This passage is probably an accretion unrelated to the Brynhild fragment, and it contains in turn a number of what are likely interpolations to the original text.

The valkyrie's drinking-speech

The first three stanzas are spoken by Sigrdrifa after she has been awoken by Sigurd (stanza 1 in Bellows 1936 corresponds to the final stanza 45 of Fafnismal in the edition of Jonsson 1905).

What is labelled as stanza 4 by Bellows (1936) is actually placed right after stanza 2, introduced only by Hon qvaþ ("she said"), marking it as the reply of the valkyrie to Sigmund's identification of himself in the second half of stanza 1.

The following two stanzas are introduced as follows:

- Sigurþr settiz niþr oc spurþi hana nafns. Hon toc þa horn fult miaþar oc gaf hanom minnisveig:

- "Sigurth sat beside her and asked her name. She took a horn full of mead and gave him a memory-draught."

Henry Adams Bellows stated in his commentary that stanzas 2-4 are "as fine as anything in Old Norse poetry" and these three stanzas constituted the basis of much of the third act in Richard Wagner's opera Siegfried. This fragment is the only direct invocation of the Norse gods which has been preserved, and it is sometimes dubbed a "pagan prayer".[5]

The first two stanzas are given below in close transcription (Bugge 1867), in normalized Old Norse (Jonsson 1905) and in the translations by Thorpe (1866) and of Bellows (1936):

| Heill dagr heilir dags synir |

Heill dagr, heilir dags synir, |

Hail Dag, Hail Dag's sons, |

Hail, day! Hail, sons of day! |

Runic stanzas

Stanzas 5-18 concern runic magic, explaining the use of runes in various contexts.

In stanza 5, Sigrdrifa brings Sigurd ale which she has charmed with runes:

Biór fori ec þer / brynþings apaldr! |

Beer I bring thee, tree of battle, |

Stanza 6 advises to carve "victory runes" on the sword hilt, presumably referring to the t rune named for Tyr:[11]

Sigrúnar þú skalt kunna, |

Victory runes you must know |

The following stanzas address Ølrunar "Ale-runes" (7), biargrunar "birth-runes" (8), brimrunar "wave-runes" (9), limrunar "branch-runes" (10), malrunar "speech-runes" (11), hugrunar "thought-runes" (12). Stanzas 13-14 appear to have been taken from a poem about the finding of the runes by Odin. Stanzas 15-17 are again from an unrelated poem, but still about the topic of runes. The same holds for stanzas 18-19, which return to the mythological acquisition of the runes, and the passing of their knowledge to the æsir, elves, vanir and mortal men.

Allar váro af scafnar / þer er váro a ristnar, |

18. Shaved off were the runes that of old were written, |

Gnomic stanzas

Stanzas 20-21 are again in the setting of the frame narrative, with Brynhild asking Sigurd to make a choice. They serve as introduction for the remaining part of the text, stanzas 22-37 (of which, however, only 22-28 and the first line of 29 are preserved in Codex Regius), which are gnomic in nature. Like Loddfafnismal, the text consists of numbered counsels, running from one to eleven. The "unnumbered" stanzas 25, 27, 30, 34 and 36 are considered interpolations by Bellows (1936).

Editions and translations

- Benjamin Thorpe (trans.), The Edda Of Sæmund The Learned, 1866 online copy, at northvegr.org

- Sophus Bugge, Sæmundar Edda, 1867 (edition of the manuscript text) online copy

- Henry Adams Bellows (1936) (translation and commentary) online copy, at sacred-texts.com

- Guðni Jónsson, Eddukvæði: Sæmundar-Edda, 1949 (edition with normalized spelling)online copy

- W. H. Auden and P. B. Taylor (trans.), The Elder Edda: A Selection, 1969

References

- The title Brynhildarljóð is used especially in reference to those parts of the Sigrdrífumál which are quoted in the Völsunga saga. See Pétursson (1998), I.460f.

- sigrdrífa occurs both as a common noun, a synonym of valkyrja, and as a proper name of the valkyrie named Hild or Brynhild in the Prose Edda. H. Reichert, "Sigrdrifa (Brynhildr)" in: McConnell et al. (eds.), The Nibelungen Tradition: An Encyclopedia, Routledge (2013), p. 119. H. Reichert, "Zum Sigrdrífa-Brünhild-Problem" in: Mayrhofer et al. (eds.), Antiquitates Indogermanicae (FS Güntert), Innsbruck (1974), 251–265.

- Orchard (1997:194). Simek (2007:284).

- "Even its customary title is an absurd error. The mistake made by the annotator in thinking that the epithet 'sigrdrifa,' rightly applied to Brynhild as a 'bringer of victory,' was a proper name has already been explained and commented on (note on Fafnismol, 44). Even if the collection of stanzas were in any real sense a poem, which it emphatically is not, it is certainly not the 'Ballad of Sigrdrifa' which it is commonly called. 'Ballad of Brynhild' would be a sufficiently suitable title, and I have here brought the established name 'Sigrdrifumol' into accord with this by translating the epithet instead of treating it as a proper name." "Victory-bringer: the word thus translated is in the original 'sigrdrifa.' The compiler of the collection, not being familiar with this word, assumed that it was a proper name, and in the prose following stanza 4 of the Sigrdrifumol he specifically states that this was the Valkyrie's name. Editors, until recently, have followed him in this error, failing to recognize that 'sigrdrifa' was simply an epithet for Brynhild. It is from this blunder that the so-called Sigrdrifumol takes its name. Brynhild's dual personality as a Valkyrie and as the daughter of Buthli has made plenty of trouble, but the addition of a second Valkyrie in the person of the supposed 'Sigrdrifa' has made still more." (Bellows 1936)

- Steinsland & Meulengracht 1998:72

- Sophus Bugge, Sæmundar Edda (1867). Cursive type indicates expansions from scribal abbreviations.

- ed. ed. Finnur Jonsson (1905), 320ff.

- Benjamin Thorpe (trans.), Rasmus B. Anderson (ed.), The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigufsson, Norroena Society (1906).

- Bellow's translation "her daughter" is based on the interpretation of the text as referring to Jörd. Sophus Bugge (1867) has argued against this interpretation, as the Earth is addressed directly in the following stanza. The literal meaning of nipt is "female relative" more generally and may refer to a sister, daughter or sister's daughter. The translation by Benjamin Thorpe renders the word as a proper name, as Nipt.

- Henry Adams Bellows, The Poetic Edda (1936)

- Enoksen, Lars Magnar. Runor: Historia, tydning, tolkning (1998) ISBN 91-88930-32-7

- Jansson; 1987: p.15

- Bellows (1936). In brackets are the lines considered "spurious additions" to stanza 19 by this editor, who however cautions that "the whole stanza is chaotic."

- Jansson, Sven B. F. (Foote, Peter; transl.)(1987). Runes in Sweden. ISBN 91-7844-067-X

- Steinsland, G. & Meulengracht Sørensen, P. (1998): Människor och makter i vikingarnas värld. ISBN 91-7324-591-7

- Einar G. Pétursson, Hvenær týndist kverið úr Konungsbók Eddukvæða? , Gripla 6 (1984), 265-291

- Einar G. Pétursson, Eddurit Jóns Guðmundssonar lærða: Samantektir um skilning á Eddu og Að fornu í þeirri gömlu norrænu kölluðust rúnir bæði ristingar og skrifelsi: Þættir úr fræðasögu 17. aldar, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi, Rit 46 (1998), vol I, pp. 402–40: introduction to Jón's commentary on the poem Brynhildarljóð (Sígrdrífumál) in Völsunga saga; vol. II, 95-102: the text of the commentary.