Siege of Temeşvar (1716)

The Siege of Temeşvar was a siege during the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718). The siege lasted from 31 August to 12 October, with a decisive victory for the Habsburg Monarchy, led by Prince Eugene of Savoy. The city fell after multiple failed attempts to break the siege, and multiple rounds of heavy bombardment of the fortress' defenses, which were mostly made of earth strengthened by palisades made of tree trunks. The city remained under military administration until 6 June 1778, when it was handed over to the administration of Kingdom of Hungary.

| Siege of Temeşvar (Timișoara) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718) | |||||||

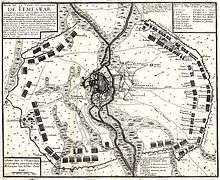

Siege of Temeşvar, Anonymous engraving | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 45,000 | 16,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,407 killed 4,190 wounded[1] |

3,000 killed 3,000 wounded[2] | ||||||

Background

Towards the end of the 17th century, the Ottoman Empire entered a period of stagnation. In 1686, the Habsburgs conquered Buda and in 1688 the fortresses located on the Mureș River: Szeged – Arad – Lipova, but in the following years the latter switched hands, with various commanders. Between late 1689 and early 1690, the Ottoman Empire conducted a long siege of Timișoara Fortress which ended with the Habsburgs’ retreat. In mid-1695, Sultan Mustafa II visited the Timișoara and Lipova fortresses, and ordered their reinforcement. In July 1696, the Habsburg army under the command of Augustus II the Strong besieged Timișoara; his engineers positioned artillery and other military engineering works around the fortress in early August. This siege failed and the Habsburgs were forced to retreat.[3][4][5][6] Prince Eugene of Savoy's army crossed the Tisa River on 11 September 1697, defeating the Ottoman army at the Battle of Zenta.[7][8][9]

On 5 August 1716, Eugene of Savoy won another victory over the Ottoman army at Petrovaradin. With enough resources for further action he headed towards Timișoara. The Habsburg Army had about 45,000 men, more than 23,000 horses, 50 field guns and 87 siege cannons. The Ottoman garrison, led by Bodor Mustafa Pasha,[10] consisted of approximately 16,000 men and 150 cannons.[11][12][13]

Siege

The fortifications were always being fixed; but most were made of earth hardened by palisades of whitewashed tree trunks, which were ineffective against 18th century cannons. The only masonry buildings were the castle, the mosques and the courtain surrounding the castle – the southern part of the city, the Angevin Fortress. All of the other buildings were made of wood, making them prone to destruction by fire.[14][15] On 21 August 1716, General Joachim Ignaz von Rotenhan reached Timișoara with 14 cavalry squadrons (1662–1736). On 25 August, 16 cavalry regiments under the command of János Pálffy and 10 infantry battalions under the command of Charles Alexander, Duke of Württemberg arrived in Beregsău Mare. The other troops, including Eugene of Savoy's, arrived on 26 August. János Pálffy and his cavalry settled to the south of the fortress, with the purpose of blocking any Ottoman attempts to fetch reinforcements. Eugene of Savoy set up his General Staff, infantry, artillery and some cavalry to the northern part of the fortress, completely surrounding it. The besiegers had approximately 30,000 hand grenades and 760 tons of gunpowder.[5][11][16][17] On 28 August, the besiegers captured the summer residence of the Turkish Governor, Pasha's Well, which the Ottomans set on fire before they retreated.[5][11][17] The siege began on 31 August. Between 1 and 15 September, the armies prepared for the battle. 3,000 people dug zigzag and parallel trenches alongside Palanca Mare. On 5 September, the first two batteries with nine cannons were installed and on 6 September there was another battery with five cannons whose fire covered the military works. On September 8, the trenches almost reached the palisade and began the filling of the moat with fascines. To prevent this, on the night of 9 September, the Ottomans attacked the trenches with torches to ignite the fascines but they were repulsed because the torches indicated the target's position. On 10 September, the Schönborn Dragoon Regiment fought off another Ottoman attack.[5][16][17][18] Beginning 16 September, the bombardment spread on the battlefield, growing in intensity as the cannons arrived and were installed. The first proposition to surrender was addressed on 17 September and was refused by the Ottomans. Between 20 September and 22 September the first breaches appeared in the walls and the wife and two sons of the beylerbey had been killed in their own house during the bombardment.[5][16][17]

In the meantime, another army corps consisting of 14 cavalry squadrons, 4 infantry battalions, 3 companies of grenadiers and 2 regiments of cuirassiers fighting under the command of General Count Étienne de Stainville (? – 1720) – commander of the imperial troops from Sibiu, then governor of Transylvania and Oltenia during the Austrian occupation – arrived in Timișoara from Alba Iulia. At the time, Eugene of Savoy controlled 70 regiments; 32 of which were infantry (69 battalions), 10 dragoon regiments (60 squadrons), 22 cavalry regiments (134 squadrons) and 6 hussar regiments (31 squadrons).[5][16][17][18][19][20][21] On 25 September the bombardment from both sides was very intense. The following day, the Ottoman troops from Belgrade arrived; they attempted to supply the fortress and attacked three times from the south to break through the encirclement. Simultaneously, the defenders of the fortress attacked but the rescuing troops attacked before the agreed time and, with no help from inside the fortress, had been pushed back. The attack from the fortress had also been repulsed because of the lack of organization, so the rescuing party was forced to turn back.[5][16][17][18] On 30 September the counterguard was conquered at the cost of 455 deaths – of which 64 were officers – and 1,487 wounded, including 160 officers. Between 1 October and 10 October, new preparations were being made and cannons were being placed. On October 11, a new, massive bombardment with the aim of destroying the fortifications began. The attack was carried out by 43 pieces of heavy artillery and continued throughout the night.[5][17][22][23]

Aftermath

On 12 October at 11:30, the white flag of surrender appeared on a bastion.[5][17][22][23] The terms of surrender were:[1][2][24][25][26]

- The Ottomans could leave with their families and goods.

- The army could come out with their weapons and belongings, and their way to Belgrade was to be completed in eight stages (Timiș River – Șag – Jebel – Deta – Margita – Alibunar – Pančevo – Borča – Zemun) under escort until Borča if they left hostages in Timișoara until they crossed the Danube;

- They would be provided with 7,000 wagons for transportation – unrealistic request, they were given what was found, namely 1,000;

- They would be provided with food along the way at a decent, proper price (not profiteering);

- The convoy would be safe from attacks en route;

- They could not take the artillery and ammunition, which were considered spoils of war; all of the cannons – of which about 120 had the Habsburg emblem on them, won over during the years – as well as 280 tons of gunpowder and 170 tons of lead, were left behind;[27][28]

- All of the others would be allowed to leave or to stay – permitted for Romanians, Serbians, Armenians, Jews and Gipsies with the exception of the Habsburg deserters;

- The same for the kurucs, they were allowed to leave or stay.

- Those who chose to leave to be allowed to sell whatever they wished;

- The guarantee of this understanding.

The Ottomans left the fortress on 17 October; the following day, Eugene of Savoy entered the Timișoara Fortress. 466 Romanians and orthodox Serbians, as well as 144 Jews and 35 Armenians, remained in Timișoara.[17][27][29] After Belgrade's conquest by the Austrians in 1718, the Austro-Turkish war ended and the Treaty of Passarowitz confirmed that Banat of Temeswar – including Timișoara Fortress – belonged to the Habsburg Monarchy.[13] The city remained under military administration until 6 June 1778, when it was handed over to the Hungarian administration.[30][31] But the fortress remained under the Austrian military command until 27 December 1860, when the Banat was incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary.[32]

Footnotes

- Preyer, Monographie…, pp. 184–185

- Hațegan, Prin Timișoara…, pp. 206–209

- Ilieșiu, Monografia…, p. 65

- Hațegan, Cronologia…, pp. 259–285

- Hațegan, Cronologia…, pp. 307–310

- Hațegan, Prin Timișoara…, pp. 141–149

- Preyer, Monographie…, p. 181

- Hațegan, Cronologia…, p. 287

- Hațegan, Prin Timișoara…, p. 157

- Hațegan, Cronologia…, p. 305

- Preyer, Monographie…, p. 182

- Hațegan, Cronologia…, p. 307

- Hațegan, Istoria…, p. 59

- Hațegan, Timișoara…, pp. 187–191

- Opriș, Mihai and Botescu, Mihai (2014). (in Romanian) Arhitectura istorică din Timișoara, Timișoara: Ed. Tempus, ISBN 978-973-1958-28-6, pp. 43–45

- Hațegan, Prin Timișoara…, pp. 178–183

- Hațegan, Istoria…, pp. 60–62

- Preyer, Monographie…, p. 183

- Cernovodeanu, P. and Vătămanu, T. N. (1977). (in French) Un médecin princier moins connu de la période phanariote : Michel Schendos van der Bech (1691–env. l736) Archived 31 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Balkan Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, January 1977, ISSN 2241-1674, p. 15

- Feneșan, Costin (2010) (in Romanian) O încercare nereușită de unire religioasă în Banatul de munte (1699), Banatica, nr. 20/2, Annex, p. 196

- (in German) Krieg zwischen den Türken, dem Kaiser und Venedig: Einzelne kriegerische Vorfälle: Schlachtordnung der Kaiserlichen im Lager vor Temeswar, 20. September 1716, Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (DDB), Karte VHK 17-14

- Szentkláray, Temesvár ostroma, Általános roham

- Hațegan, Prin Timișoara…, p. 204

- Szentkláray, A kapituláczió, A török elvonulása

- Ilieșiu, Monografia…, pp. 65–73

- Hațegan, Istoria…, pp. 62–63

- Hațegan, Cronologia…, p. 312

- Hațegan, Prin Timișoara…, p. 187

- Ilieșiu, Monografia…, p. 73

- Preyer, Monographie…, pp. 94, 210

- Hațegan, Istoria…, p. 93

- Preyer, Monographie…, pp. 114–115, 227–228

References

- Preyer, Johann Nepomuk (1995). (in German and Romanian) Monographie der königlichen Freistadt Temesvár – Monografia orașului liber crăiesc Timișoara, Timișoara: Ed. Amarcord, ISBN 973-96667-6-0

- Jenő Szentkláray (1911). (in Hungarian) Temes vármegye története – Temesvár története, Magyarország vármegyéi és városai cycle, Budapest (online version)

- Ilieșiu, Nicolae (1943). (in Romanian) Timișoara: Monografie istorică, Timișoara: Editura Planetarium, 2nd ed., ISBN 978-973-97327-8-9

- Hațegan, Ioan (2005). (in Romanian) Cronologia Banatului: Vilayetul de Timișoara, vol. II, part 2, Timișoara: Ed. Banatul, ISBN 973-7836-54-5 (online version)

- Hațegan, Ioan (2006). (in Romanian) Prin Timișoara de odinioară: I. De la începuturi până la 1716, Timișoara: Ed. Banatul, ISBN 973-97121-8-5 (online version)

- Hațegan, Ioan and Petroman, Cornel (2008). (in Romanian) Istoria Timișoarei, vol. I, Timișoara: Ed. Banatul, ISBN 978-973-88512-1-4