Siege of Fort Stanwix

The Siege of Fort Stanwix (also known at the time as Fort Schuyler) began on August 2, 1777, and ended August 22. Fort Stanwix, in the western part of the Mohawk River Valley, was then the primary defense point for the Continental Army against British and Indian forces aligned against them in the American Revolutionary War. The fort was occupied by Continental Army forces from New York and Massachusetts under the command of Colonel Peter Gansevoort. The besieging force was composed of British regulars, American Loyalists, Hessian soldiers from Hesse-Hanau, and Indians, under the command of British Brigadier General Barry St. Leger and the Iroquois leader Joseph Brant. St. Leger's expedition was a diversion in support of General John Burgoyne's campaign to gain control of the Hudson River Valley to the east.

One attempt at relief was thwarted early in the siege when a force of New York militia under Nicholas Herkimer was stopped in the August 6 Battle of Oriskany by a detachment of St. Leger's forces. While that battle did not involve the fort's garrison, some of its occupants sortied and raided the nearly empty Indian and Loyalist camps, which was a blow to the morale of St. Leger's Indian support. They killed some Seneca. The siege was finally broken when American reinforcements under the command of Benedict Arnold neared, and Arnold used a ruse, with the assistance of Herkimer's relative Hon Yost Schuyler, to convince the besiegers that a much larger force was arriving. This misinformation, combined with the departure of Indian fighters not interested in siege warfare and upset over their losses from the raids, led St. Leger to abandon the effort and retreat.

St. Leger's failure to advance on Albany contributed to Burgoyne's surrender following the Battles of Saratoga in October 1777. Although St. Leger reached Fort Ticonderoga in late September, he was too late to aid Burgoyne.

The first official US flag was flown during battle on August 3, 1777, at Fort Schuyler. The Continental Congress adopted the following resolution on June 14, 1777: "Resolved, that the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white, on a blue field, representing a new constellation." There was a delay in displaying this flag. The resolution was not signed by the secretary of the Congress until September 3, though it was previously printed in the newspapers. Massachusetts reinforcements to Fort Schuyler brought news of the adoption by Congress of the official flag. Soldiers cut up their shirts to make the white stripes; scarlet material was secured from red flannel petticoats of officers' wives, while material for the blue union was secured from Capt. Abraham Swartwout's blue cloth coat. A voucher shows that Congress paid Capt. Swartwout for his coat for the flag.[3]

Background

Fort Stanwix occupied a strategic western portage known as the Oneida Carrying Place (site of modern Rome, New York) between the Mohawk River, which flowed southeast to the Hudson River, and Wood Creek, whose waters ultimately led to Lake Ontario. Built by the British in 1758 during the French and Indian War on the only dry ground in the area, the fort had fallen into disrepair. When the American Revolutionary War widened in 1776 to include the frontier areas between New York and the Province of Quebec, the site again became strategically important.[4]

British Colonial Secretary Lord Germain and General John Burgoyne developed a plan for gaining control of the Hudson River valley that included an expedition that King George described as a "diversion on the Mohawk River".[5] In March 1777 Germain issued orders assigning the expedition to Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger, an experienced frontier fighter who had served in the French and Indian War.[6][7]

Forces assemble

In April 1777, Continental Army Major General Philip Schuyler ordered the 3rd New York Regiment under the command of Colonel Peter Gansevoort to occupy and rehabilitate the fort as a defense against British and Native incursions from Quebec. Arriving in May, they immediately began working on the fort's defenses. Although they officially renamed the fort to Fort Schuyler, it was still widely known by its original name. Warnings from the friendly Oneida Indians that the British were planning an expedition to the Mohawk Valley were confirmed by mid-July, spurring the pace of the work.[8][9] In early July, Gansevoort reported on the state of affairs to Schuyler, noting that provisions and ammunition were in short supply. Schuyler ordered additional supplies sent to the fort on July 8.[10]

St. Leger, who was brevetted a brigadier general for the expedition, assembled a diverse force consisting of British regulars from the 8th and 34th Regiments, a number of artillerymen, 80 jäger from Hesse-Hanau, 350 Loyalists from the King's Royal Regiment of New York, a company of Butler's Rangers, and about 100 Canadien laborers.[7] His artillery consisted of two six-pound pieces, two 3-pounders, and four small mortars. He expected these to be adequate for the taking of a dilapidated fort with about 60 defenders, which was the latest intelligence he had when the expedition left Lachine, near Montreal, on June 23.[7][11]

St. Leger first learned that the Americans had occupied Stanwix in force when prisoners captured from its garrison were brought to him on the St. Lawrence.[12] He learned from the prisoners that Fort Stanwix had been repaired and was "garrisoned by upwards of 600 men ... and the rebels are expecting us, and are acquainted with our strength and route".[13] Daniel Claus, the Indian agent accompanying the expedition, convinced St. Leger to go to Oswego, where a body of Indians could be recruited.[14] They arrived at Oswego, New York on July 14,[7] where Joseph Brant and about 800 Indians joined the expedition. These consisted mainly of Mohawks and Senecas, but there were also warriors from the other tribes of the Iroquois League (other than the Oneidas and the Tuscaroras, who still claimed neutrality), and some Indians from the Great Lakes area.[13][15]

After leaving Oswego another report reached St. Leger that more supplies were en route to the fort. The movement of his main force up Wood Creek from their landing on the eastern shore of Lake Oneida had been blocked by the Stanwix defenders just a week earlier by felling trees across the creek; St. Leger's forces were rebuilding an old military road to reach Fort Stanwix. St. Leger immediately dispatched Brant with 200 Indians and 30 regulars to intercept those supplies, but Brant's arrival at the fort on August 2 was too late.[16][17] The supply convoy, which was guarded by 200 men from the 9th Massachusetts Regiment, had arrived and been unloaded. Brant's men were able to capture the convoy's boat captain; the Massachusetts men remained in the fort.[18] St. Leger's main force arrived the next day,[14] although the artillery did not arrive for several more days.[16]

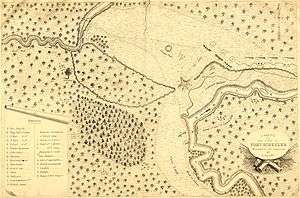

Siege begins

At first, St. Leger tried to intimidate the fort's occupants by parading his troops—including the Indians in their war dress—in front of the fort. When this failed he sent a truce flag bearing a proclamation authored by General Burgoyne; Gansevoort refused to respond. St. Leger then began siege operations, encamping the regulars and artillery on a low rise north of the fort, and most of the Indians and Loyalists to its south,[19] with a picket line of Indian encampments along the Mohawk River.[20]

St. Leger's artillery was held up by a tactic that was also used to slow down Burgoyne's army after the fall of Ticonderoga: Gansevoort and his men had systematically felled trees across the wooded track the expedition came down, and St. Leger needed to clear the track to make way for his artillery. This work occupied all but 250 of St. Leger's white men, with the actual encirclement of the fort dominated by Indians.[19]

On August 5, St. Leger received word from Joseph Brant's sister Molly that an American relief column was marching up the Mohawk valley.[19]

Oriskany

The Tryon County Committee of Safety received news of St. Leger's movements on July 30, and set about raising additional troops. On August 4, about 800 men from the Tryon County militia were mustered at Fort Dayton (near modern Herkimer, New York) by Nicholas Herkimer, the committee chairman.[21] By late the next day the column had arrived within 10 miles (16 km) of Fort Stanwix. St. Leger, on learning of their approach, sent Johnson with a small number of regulars and rangers, along with Brant and most of the Indians, to oppose Herkimer's advance.[22] They set up an ambush, and in a bloody confrontation near Oriskany Creek, both sides suffered significant casualties, including Herkimer, who suffered a serious wound to the leg. The Americans drove St. Leger's detachment back, but Herkimer (who eventually died of his wounds) was forced to retreat back to Fort Dayton due to the large number of casualties. The confrontation came at another cost to St. Leger. Gansevoort's besieged men took advantage of the absence of a sizable part of St. Leger's force to make a sortie, in which Gansevoort's second-in-command, Marinus Willett, led 250 men out and looted the nearly empty Indian camps of "several wagon-loads of spoils",[23] including John Johnson's orderly book, plans for the expedition, and a letter the British had intercepted from Gansevoort's fiancée.[24] The tale of this party recovering actual wagonloads of materials is probably untrue. It likely dates to a memoir by Marinus Willett written late in his life; no contemporaneous accounts of the sortie, including Willett's earlier journals, mention the need for wagons.[25]

_by_Charles_Bird_King.jpg)

When the British force returned from Oriskany they arrived at a camp that had been stripped of much, including personal belongings and the blankets the Indians slept in. Combined with the fact that the battle at Oriskany had cost so many Indian lives, this greatly upset the Indians. They had been told that the white men, who had thus far fought relatively little, would do most of the fighting.[26] This breach of trust damaged relations between the Indians and St. Leger, and became instrumental in the eventual failure of the siege.[27]

St. Leger took advantage of his victory to deliver another demand for the fort's surrender, which Gansevoort also rejected. The next day St. Leger sent in a third surrender demand, which included (false) news that Burgoyne was in Albany as well as threats that the Indians would be permitted to massacre the garrison and destroy the Mohawk valley communities from which the garrison was drawn.[28] In an eloquent refusal, Lieutenant Colonel Willett responded, "By your uniform you are British officers. Therefore let me tell you that the message you have brought is a degrading one for a British officer to send and by no means reputable for a British officer to carry."[29]

Taking advantage of a brief truce, Gansevoort sent Willett and another officer out on August 8 to notify Schuyler of their situation.[30] After making their way through swampy territory on the British lines, they continued down the Mohawk valley, eventually meeting a relief column under the command of Major General Benedict Arnold.[29]

Siege relief

Schuyler had received early reports of the action at Oriskany on August 8,[31] and dispatched Ebenezer Learned's 4th Massachusetts Regiment to relieve the besieged fort the next day.[32] On August 12, even before Willett could reach him, Schuyler held a war council to decide how to deal with the combined threats of St. Leger and Burgoyne, whose large army had reached the Hudson River.[33] Amid concerns that the withdrawal from Ticonderoga by General Arthur St. Clair would be repeated at Stanwix, the council decided, with near unanimity, not to send a relief column to Fort Stanwix. In opposition to the council, Schuyler insisted on a relief expedition, which Arnold offered to lead.[34] In addition to Schuyler's actions, Major General Israel Putnam, based in Peekskill, New York, on August 14 dispatched two regiments (the 1st Canadian and the 2nd New York), which were already on guard duty in the Mohawk River valley. These two units were still en route when the siege was lifted, and turned back.[35]

By August 20, Arnold, Willett and 700 Continental Army regulars had arrived at Fort Dayton.[36] In an attempt to enlarge his force, Arnold tried to interest the Tryon County men in another attempt against St. Leger, but raised only about 100 men. He then decided to wait, hoping that friendly Oneidas and Tuscaroras could be convinced to join the effort, or that a request to Schuyler for another 1,000 men would be fulfilled.[29] However, news reached him that the siege had reached a critical stage, and that action was necessary. St. Leger had learned that his guns were largely ineffective against the fort's walls from long range, so he began entrenching operations to establish positions closer to the fort. Gansevoort reported that the siege trenches had reached within striking distance of one of the fort's bastions.[37]

Uncomfortable with the number of troops available to him, Arnold opted for a deception to sow trouble in the British camp. While at Fort Dayton, a number of Loyalists had been arrested, including Hon Yost Schuyler.[27] Arnold convinced Hon Yost, a member of the King's Royal Regiment of New York who grew up with many of the Mohawk Indians attacking Fort Stanwix,[38] to spread rumors that large numbers of Americans, under the command of "The Dark Eagle", were about to descend on St. Leger's camp.[27] Hon Yost's good conduct was assured by holding hostage his brother.[39]

Arnold's stratagem seems to have met with some success. St. Leger recorded on August 21 that "Arnold was advancing, by rapid and forced marches, with 3,000 men",[40] even though Arnold was still at Fort Dayton on that day.[41] When St. Leger held a council, about 200 Indians had already abandoned the camp, and in the council the remaining Indians, unhappy with siege warfare and the loss of their equipment, threatened to leave if he did not lift the siege. On August 22, St. Leger broke camp and began the trek back to Lake Ontario,[27] leaving behind a sizable amount of equipment. A number of men from St. Leger's party deserted or were captured by the fort's garrison, including Hon Yost.[2]

Aftermath

Arnold, whose force was augmented by the arrival of friendly Indians, advanced about 10 miles (16 km) toward Fort Stanwix on August 23 when a messenger from Gansevoort notified him of St. Leger's departure. Pushing on, they reached the fort that evening. Early the next day, Arnold detached 500 men to pursue St. Leger, whose column was also being taunted and harassed by his formerly supportive Indian allies.[42] An advance party reached the shores of Oneida Lake in heavy rain just as the last of St. Leger's boats were departing.[43] Leaving a garrison at the fort, with smaller outposts along the Mohawk, Arnold then hurried back with about 1,200 men to rejoin the main army.[42]

While still on Oneida Lake, St. Leger learned from an Indian messenger of the true state of Arnold's force.[44] On August 27, St. Leger wrote to Burgoyne from Oswego that he intended to join him by traveling via Lake Champlain.[45] He reached Fort Ticonderoga on September 29, too late to assist Burgoyne.[46]

Burgoyne blamed the failure of his campaign in part on St. Leger's failure to penetrate the Mohawk valley, and the lack of sufficient Loyalist support. He believed that a well-placed Loyalist uprising in upstate New York would have diverted enough American resources that either his advance or St. Leger's would have succeeded.[47] He was also hopeful that St. Leger's arrival at Ticonderoga would be sufficient to assist in his retreat.[47] However, he was already surrounded by the time St. Leger arrived at Ticonderoga, and surrendered after the Battle of Bemis Heights (second Saratoga).[48] In an analysis after the surrender, Burgoyne noted that the failure of General William Howe to support him made it possible for Washington to divert resources from the area around New York City to assist both in the relief of Stanwix and at Saratoga.[49]

Fort Stanwix itself saw little action after the siege, although it was a dangerous and unpopular posting because of regular harassment by Loyalists and hostile Indians.[50] In the spring of 1779 the Continental Army used the fort as a staging ground for the destruction of Onondaga Castle.[51] In 1780, the garrison was blockaded for several days by a large force of Indians led by Joseph Brant.[52] Finally, in the spring of 1781, when flood and fire (most likely arson) destroyed most of the fort, the Americans evacuated the post.[53]

Legacy

Fort Stanwix was eventually destroyed in the 19th century.[54] The site was designated a U.S. National Monument in 1935, although the land itself was then occupied by private businesses and residences in downtown Rome, New York.[55] In 1961 the site was designated a National Historic Landmark, and in 1966 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[56][57] The fort was reconstructed in the 1970s by the National Park Service, creating the current Fort Stanwix National Monument.[58]

Notes

- British casualties are as reported by St. Leger in Watt (2002), pp. 320–321, which include casualties from Oriskany. Watt notes that St. Leger does not report Canadien casualties, and probably underreported some of British casualties.

- Watt (2002), p. 258

- Connell, R.W.; Mack, W.P. (2004). Naval Ceremonies, Customs, and Traditions. Naval Institute Press. p. 140. ISBN 9781557503305. Retrieved 2015-06-03.

- Nickerson (1967), p. 197

- Nickerson (1967), p. 90

- Nickerson (1967), p. 92

- Pancake (1977), p. 140

- Pancake (1977), p. 139

- Nester (2004), p. 170

- Scott (1927), pp. 138, 166

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 195–197

- Nickerson (1967), p. 198

- Pancake (1977), p. 141

- Nickerson (1967), p. 199

- Nester (2004), p. 169

- Glatthaar (2006), p. 158

- Luzader (2008), p. 127.

- Scott (1927), p. 175

- Nickerson (1967), p. 200

- Scott (1927), p. 179

- Pancake (1977), p. 142

- Pancake (1977), p. 143

- Pancake (1977), p. 144

- Watt (2002), p. 196

- Scott (1927), p. 195

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 269–270

- Pancake (1977), p. 145

- Nickerson (1967), p. 270

- Nickerson (1967), p. 271

- Watt (2002), p. 208

- Scott (1927), p. 260

- Scott (1927), p. 264

- Nickerson (1967), p. 211

- Nickerson (1967), p. 212

- Scott (1927), pp. 267, 292

- Scott (1927), p. 269

- Nickerson (1967), p. 272

- Watt (2002)p. 224, 258

- Nickerson (1967), p. 273

- Scott (1927), p. 281

- Scott (1927), p. 282

- Nickerson (1967), p. 275

- Watt (2002), pp. 260–261

- Watt (2002), p. 262

- Nickerson (1967), p. 276

- Nickerson (1967), p. 354–355

- Scott (1927), p. 300

- Ketchum (1997), pp. 423–425

- Scott (1927), pp. 306–307

- Watt (2002), p. 313

- Glatthaar (2006), pp. 241–244

- Watt (1997), p. 81

- Watt (2002), p. 314

- Pitcaithley (1981)

- Official NPS page for Fort Stanwix National Monument

- NHL summary description

- NRHP Listing

- Zenzen (2008) describes the reconstruction.

References

- Glatthaar, Joseph T; Martin, James Kirby (2006). Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians and the American Revolution. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-4601-0. OCLC 63178983.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1997). Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6123-9. OCLC 41397623.

- Luzader, John F. (2010). Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781611210354. OCLC 185031179.

- Nester, William R (2004). The frontier war for American independence. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0077-1. OCLC 52963301.

- Nickerson, Hoffman (1967) [1928]. The Turning Point of the Revolution. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat. OCLC 549809.

- Pancake, John S (1977). 1777: The Year of the Hangman. University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5112-0. OCLC 2680804.

- Pitcaithley, Dwight T (1981). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Fort Stanwix" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- Scott, John Albert (1927). Fort Stanwix and Oriskany: The Romantic Story of the Repulse of St.Legers British Invasion of 1777. Rome, NY: Rome Sentinel Company. OCLC 563963.

- Watt, Gavin (1997). The Burning of the Valleys: Daring Raids From Canada Against the New York Frontier in the Fall of 1780. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-271-1. OCLC 317810982.

- Watt, Gavin K; Morrison, James F (2002). Rebellion in the Mohawk Valley: The St. Leger Expedition of 1777. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-376-3. OCLC 49305965.

- Zenzen, Joan M. (2008). Fort Stanwix National Monument: reconstructing the past and partnering for the future. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7433-4. OCLC 163593261. See also the 2004 report on which the book is based: Zenzen, Joan (June 2004). "Reconstructing the Past, Partnering for the Future: An Administrative History of Fort Stanwix National Monument". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2007-08-09.

- "Official NPS page for Fort Stanwix National Monument". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- "NHL summary description for Fort Stanwix". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2015-06-22.

- "Fort Stanwix - asset detail".. See also: "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

Further reading

- Campbell, William W (1880). Annals of Tryon County, Or, The Border Warfare of New York, During the Revolution: Or, The Border Warfare of New York During the Revolution. Cherry Valley Gazette Print. OCLC 7353443.

- Johnson, John; Stone, William Leete; De Peyster, John Watts; Myers, Theodorus Bailey (1882). Orderly book of Sir John Johnson during the Oriskany Campaign, 1776–1777. Albany: J. Munsell's Sons. OCLC 2100358.