Siege of Algeciras (1342–44)

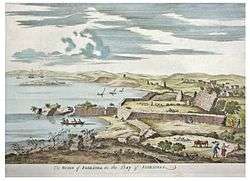

The Siege of Algeciras (1342–44) was undertaken during the Reconquest of Spain by the Castillian forces of Alfonso XI assisted by the fleets of the Kingdom of Aragon and the Republic of Genoa. The objective was to capture the Muslim city of Al-Jazeera Al-Khadra, called Algeciras by Christians. The city was the capital and the main port of the European territory of the Marinid Empire.

The siege lasted for twenty one months. The population of the city, about 30,000 people including civilians and Berber soldiers, suffered from a land and sea blockade that prevented the entry of food into the city. The Emirate of Granada sent an army to relieve the city, but it was defeated beside the Río Palmones. Following this, on 26 March 1344 the city surrendered and was incorporated into the Crown of Castile. This was one of the first military engagements in Europe where gunpowder was used.

Sources

Despite the remarkable significance of the siege and fall of Algeciras, there are few contemporary written sources that recount the events. The most important work is the Chronicle of Alfonso XI, which tells the main events of the reign of King Alfonso XI, and whose chapters describing the siege of Algeciras were written by the royal scribes in the Christian camp. This book recounts in detail the events as seen from outside the city, devoting a chapter to each month. Other Castillian works are the Poem of Alfonso Onceno, called the "rhyming chronicle", written by Rodrigo Yáñez, and the Letters of Mateo Merced, Vice Admiral of Aragon, with a report to his king on the entry of the troops into the city.[1][2]

All of these sources tell of the siege of the city from the perspective of the besiegers. No accounts of the events as seen from inside the city have survived to modern times. There is a total absence of Muslim sources, perhaps because of the absence of good writers in the city or perhaps due to a desire not to dwell on the loss of such an important city. Translations of some of the few Arabic texts that refer indirectly to the loss of the city are all that is available to cover this aspect of the history of the siege.[3]

Background

Moorish threat to Castile

Algeciras was formerly part of the Emirate of Granada. In 1329 the city was taken over by the King of Morocco, who made it the capital of his European domains. Forces from Granada and Morocco recovered the nearby city of Gibraltar in 1333. In 1338 Abd-Al-Malik, son of the king of Morocco and ruler of Algeciras and Ronda, launched raids against the Castilian territories in the south of the Iberian Peninsula. In one of these raids he was killed by Castilian soldiers and his body taken back to Algeciras, where it was buried.[4]

Abd-Al-Malik's father Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman crossed the strait in 1340, defeated a Spanish fleet and landed in the city. On the grave of his son he swore to defeat the Castilian king. He first went to the town of Tarifa, to which he laid siege. King Alfonso XI of Castile, overwhelmed by the incursions of the new North African force and the possibility of losing the city of Tarifa, gathered an army with the help of King Afonso IV of Portugal.[5] The two armies, Castilian-Portuguese and Moroccan-Granadan, clashed near Tarifa's Los Lances beach in the Battle of Río Salado (30 October 1340). The defeat of the Muslims in this battle encouraged Alfonso XI and convinced him of the need to take the city of Algeciras, since it was the main port of entry of troops from Africa.[6]

Preparations

Starting in 1341, Alfonso XI began to prepare the necessary troops to lay siege to the city. He ordered construction of several ships and secured the services of the Genoese fleet of Egidio Boccanegra and squadrons from Portugal and Aragon. On land, besides his Castilian troops and troops from Aragon, there were many European crusaders, and he was supported by the kings of England and France.[7] The campaign was financed by extending the alcabala tax on bread, wine, fish, and clothing to include sales of all goods. The courts of Burgos, León, Ávila, and Zamora were called in 1342 to approve the new tax.[8][lower-alpha 1]

Alfonso XI met with the Portuguese Admiral Carlos Pessanha in El Puerto de Santa María and heard from Pero de Montada, Admiral of the Aragon squadron, that it was heading for Algeciras. He then left for Getares Cove, just 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the city, to check the status of the galleys at his disposal.[9][10] On his arrival at Getares, Pero de Montada informed the king that he had intercepted several ships carrying food to the city, and that the galleys of Portugal and Genoa had engaged eighty Moorish galleys in combat, captured twenty-six of them and forced the others to take refuge in African ports.[11] According to the Castilian knights, this was the time to encircle the city, since it should have limited supplies. The king, however, felt he still had too few troops in place. Most of his forces were in Jerez de la Frontera awaiting his orders, while the troops defending Algeciras had already been warned of their arrival.[12]

The king returned to Jerez, assembled his council and informed them of the state of the city. He sent orders to the admirals at Getares to intercept any boats trying to supply the city and to try to capture some Algecireño who could inform them about the condition of the two towns. He also sent orders to his almogavars to do the same on land. The king's knights advised him about the best places to establish the main base where the King and nobles would live, and the vulnerable points where they could do most damage to the city's defenses.[13] It was only needed to move troops to Algeciras, build bridges over the Barbate River and over a stream near Jerez, and send ships to the Guadalete River to carry food for the troops.

On 25 July 1342 Alfonso XI left Jerez accompanied by his troops and the officials and knights who were to assist him in the siege of Algeciras. These included the Archbishop of Toledo, the Bishop of Cádiz, the Master of Santiago, Juan Alonso Pérez de Guzmán y Coronel, Pero Ponce de León, Joan Núñez, Master of Calatrava, Nuño Chamizo, Master of Alcántara, Fray Alfonso Ortiz Calderón, Prior of San Juan, and the councils of Seville, Cordoba, Jerez, Jaén, Écija, Carmona, and Niebla.[14]

On 1 August the Castilian troops and their allies arrived at Getares, comprising a force of 1,600 mounted soldiers and 4,000 archers and lancers. The troops and squadrons of Aragon, Genoa, and Castile took their positions.

On 3 August the headquarters were established on a knoll to the north of Algeciras. The king lived in the tower there in the early months of the siege surrounded by the knights and nobles who accompanied him.[15] The Torre de los Adalides (Tower of the Champions), named for that time, gave an excellent view of the Muslim city and of the roads that communicate with Gibraltar and eastern Andalusia.[16]

Algeciras

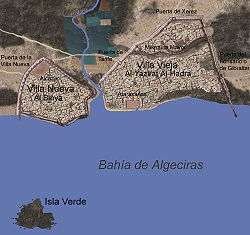

Al-Jazeera Al-Khadra was the first city founded by Muslims when they arrived in the Iberian peninsula in 711. In the fourteenth century the city was two separate towns with their own walls and defenses. Between the two towns was the Río de la Miel. The river mouth formed a wide inlet which acted as a natural harbor protected by the Isla Verde Green Island, which the Muslims called Yazirat Umm Al-Hakim. The north town, Al-Madina, called Villa Vieja ("old town") by the Spaniards, was the oldest of the two and was founded in 711. It was surrounded by a wall with towers and a deep moat protected by a barbican and a parapet. The entrance to the Villa Vieja from the Gibraltar road was protected by a massive gateway called the Fonsario, near the main city cemetery. This entrance was the weakest point of the defensive works and therefore the best defended.[17]

The south town, Al-Binya, called Villa Nueva ("new town") by the Spaniards, was built by the Marinids of Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn Abd Al-Haqq in 1285. It was on a plateau that had once held the industrial neighborhood of Iulia Traducta, the Roman Algeciras.[18] The steepness of its perimeter helped its defense, so it was not necessary to build such strong defenses as those of the Villa Vieja. The Villa Nueva housed the fortress and the troops who had been established in the city. Algeciras had about eight hundred horsemen and twelve thousand crossbowmen and archers, with a total population of thirty thousand people, according to information from captives given to the King of Castile in the early days of the siege.[19]

Phases of the siege

Opening moves: August 1342 – October 1342

From 3 August 1342, after the main camp had been established, the king of Castile commanded the Royal Engineers to study the places where troops were to be positioned. The main aim was to prevent the departure of troops from the city and the entry of reinforcements from the Tarifa and Gibraltar roads. Algeciras was to fall from hunger rather than by force of arms.[20]

Seeing from the city that the siege had not yet been properly organized, the defenders decided to send three hundred men on horseback and a thousand on foot against the Master of Santiago, Juan Alonso Pérez de Guzmán y Coronel, Pero Ponce de León and the Seville Council in the Puerta del Fonsario. The men of the Count of Lous counterattacked. They did not wait for the other Christians, and the Count and his men died under a cloud of arrows when they came too close to the wall.[20] After the king had seen the damage that could be done, in the next few days he had a trench dug around the Villa Vieja from the Río de la Miel to the sea to prevent attacks from the city. Shelters were built next to the trenches and soldiers were posted at regular intervals to stand guard at night.[21] The king moved his headquarters closer to the city and sent several of his men to conquer the Cartagena Tower in the city of Carteia, from where they could observe the movements of the Marinids of Gibraltar.

With war between Peter IV of Aragon and the Kingdom of Majorca imminent, the Aragonese fleet left the siege in September 1342.[22] Siege engines were sent to a position near the northwest gate of the city, where two great towers prevented attack and protected the defenders. During construction of these machines, several of the defenders attacked from the Puerta de Xerez to prevent placement of the engines. The Algecireños' strategy was to provoke the besiegers into coming closer to the walls. This technique, with which they had killed the Count of Lous, was not known to the Christian knights unaccustomed to the border war, and many men died during the early months of the siege. In the raid on the siege towers, the king's equerry Joan Niño died, as did the Master of Santiago[lower-alpha 2] and other men.[25]

The siege dragged on, and the King of Castile sent several of his men to seek help in order to maintain the siege. The Archbishop of Toledo was sent to meet with the King of France while the Prior of St. Joan went to call on Pope Clement VI, who had just been installed.[26]

The besiegers had more problems than they had expected at the start of the siege. During the first days of October there was a huge storm. The camp in the northwest was sited in a traditionally flooded area, and turned into a swamp. The defenders took advantage of the confusion created by the storm to attack during the night, causing extensive damage. Floods in the camp and in the encircling lines required the headquarters and the larger part of the troops to move to the mouth of the river Palmones, where they spent the remainder of October 1342. Soon after the main Christian camp had moved, the Algecireños gathered all their forces in the Villa Vieja to make a desperate attack against their besiegers. The Muslim knights were able to reach the newly established Christian camp and kill many Christian knights including Gutier Díaz de Sandoval and Lope Fernández de Villagrand, vassals of Joan Núñez and Ruy Sánchez de Rojas, vassal of the Master of Santiago.[27]

First winter: November 1342 – April 1343

The situation deteriorated gradually in both the city and the besieging camp. Food was scarce in the Christian camp after the flooding and the crowd of troops and animals in unsanitary conditions caused the spread of diseases.[28] In November, Peter IV of Aragon sent ten galleys commanded by Mateu Mercer to meet his treaty obligation. The Portuguese king Afonso IV sent another ten galleys under Admiral Carlos Pessanha, but they stayed for only three weeks, and their departure boosted the morale of the defenders.[22] The Castilian forces continued to have difficulty maintaining an adequate fleet for supply and offense.[29] However, Algeciras grew short of food due to the sea blockade.

During the first months of siege the Spaniards continued to launch rocks at the walls of the city, while the defenders tried to cause losses in direct combat or with weapons such as ballistae, which could shoot large projectiles.[30] In December 1342, troops sent by the councils of Castile and Extremadura reached the Christian camp, and with them the siege became tighter. They began to place a large number of Genoese ballistic engines around the city, while the defenders continued to shoot arrows at those installing the machines.[31] During January 1343 the continuing struggles in the lines round the city weakened both sides. A large fortified bastida, a wooden tower commanded by Iñigo López de Orozco, was built facing the Puerta del Fonsario, and from this tower missiles could be shot over the city wall.[32] The first bastida was soon burned by a force that sallied from the city, but another was built and continued shooting against the city throughout the siege.[33]

Yusuf I, Sultan of Granada, was preparing to send supplies and relief to the city. With the threat of troops from Granada, the attacks escalated against the Puerta del Fonsario in the Villa Vieja, the weakest point but also the best defended. In front of it Alfonso XI ordered construction of new covered trenches, which allowed approach to the city walls to place siege engines.[21] From Algeciras, meanwhile, the defenders fired iron projectiles from primitive gunpowder bombards, which caused extensive damage. These are said to have been the first pieces of artillery with gunpowder to be used in the peninsula.[34]

Trenches continued to be built around the city until they surrounded the entire perimeter by March 1343. Behind the trenches were earthen banks, and on these wooden walls were erected to protect the besieging soldiers, with strong towers erected at intervals.[21] Trebuchets in the Castilian camp hurled large numbers of stone balls, or bolaños.[30] The trebuchets had a maximum range of 300 metres (980 ft), and were vulnerable to parties of besiegers that were able to cross the trenches.[35] So many bolaños were launched during the siege that in 1487 King Ferdinand II of Aragon sent an expedition to the ruins of Algeciras to retrieve them so they could be used again in the siege of Málaga.[36][37][30]

Reinforcements arrived at the Christian camp from the various councils of Castile, including the knights Juan Núñez III de Lara and Juan Manuel, Prince of Villena. The fresh troops replaced the soldiers who had been injured or were weakened by hunger.[32] Starting in February 1343, the besiegers began to extend the encircling line to block the sea approaches to the city and thus prevent the arrival of food from Gibraltar. The aim was to block the sea approach to Algeciras with logs connected by chains.[38] The boom eventually extended from the Rodeo point to the south of the city to the Isla Verde, and from there to the Playa de Los Ladrillos to the north.[39] However, in late March 1343 a storm broke up the boom and the logs were washed on shore, providing a useful supply of wood to the besieged.[38]

Both sides receive reinforcements: May 1343 – September 1343

In May 1343 a large army under the Sultan of Granada passed the Guadiaro River and approached the city. Alfonso XI sent for his knights to see how they could deal with this new threat. He sent letters informing Granada he would lift the siege of the city if it paid him tribute. The Sultan of Granada offered a truce, but it was not enough for the Castilians.[40]

The same month saw the arrival of numerous European knights: from England came the earls of Derby and of Salisbury;[41] from Germany came Count Bous; from France came Gaston II, Count of Foix, and his brother Roger-Bernard, Viscount of Castelbon, and King Philip III of Navarre with supplies and troops.[42]

The troops of Granada held their position, waiting for the right moment to approach the city. During the months of June and July the situation remained unchanged. More fortified siege towers and trenches were built as fighting continued around the city. The defenders used ballistae, engines that were probably similar to catapults, and the "thunders", as the new gunpowder bombards were called by the Muslims, causing major damage to the siege forces and mainly targeting the siege towers and trenches.[43]

In August 1343, while negotiations were continuing between Castile and Granada, news arrived that in Morocco King Abu al-Hasan Ali was preparing a fleet to come to the aid of the city. Faced with the imminent entry into the struggle of forces from Granada and Morocco, it became urgent for the Christians to accelerate plans for the conquest of Algeciras. Simultaneously, Alfonso de Castilla heard that the Pope would give the kingdom 20,000 florins to defray the expenses of the campaign, and the King of France through the Archbishop of Toledo, Gil Álvarez Carrillo de Albornoz, would supply 50,000 florins. With this money the Spaniards could pay the Genoese mercenaries, who had long been demanding their pay.[44] The difficulties of the Christians in the siege and the urgency of battle with Granada and Morocco were known throughout the kingdom. The King of Castile had to pawn his crown and send several of his silver belongings to be melted in Seville after a fire reduced the camp's store of flour to ashes.[45]

At the same time, Aragon provided new ships to help maintain the siege: the Vice Admiral of Valencia, Jaime Escribano, arrived in mid-August with ten Aragonese galleys.[46] These boats and another fifteen Castilian ships commanded by Admiral Egidio Boccanegra were sent to Ceuta to do as much damage as possible to the fleet of the King of Morocco, who was waiting at this port for the arrival of the fleet from Granada to go to Algeciras' aid.[47] In the first encounter, the Christians tried to surprise the Muslim fleet by sending into combat only the fifteen Castilian ships, while the Aragonese ships maneuvered as if preparing to go to the aid of the Moroccans. The strategy would have been expensive to the Moroccans had they not captured a Castilian sailor before the final encounter, who warned them of the ruse. The ships from Ceuta quickly returned to port and the Christian fleet had to return to the Bay of Algeciras.[48] On his return at the siege, Egidio Boccanegra sent twenty of his ships to wait at Getares, ready to intercept the Moors if they decided to attack the encirclement.

Moroccan troops cross the strait: October 1343 – November 1343

In October 1343 the Moroccan fleet crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and reached Getares. As soon as the first warning fires of the Christian beacons were seen, forty Castilian and Aragonese ships stationed themselves at the southern entrance of the city, but the boats from North Africa did not head to Algeciras, instead taking shelter in the nearby port of Gibraltar.[49]

A battle between the galleys threatened to break out. Warned of this, the Genoese squadron began to embark all that belonged to them in order to leave. With all their equipment in their ships, the Admiral Egidio Boccanegra informed the king that if they were not paid four months of arrears for service they would leave the siege. It was already known that the Genoese sailors had been dealing with the Marinids of Gibraltar and Ceuta, and the relations between them were far from hostile. It was feared in the headquarters that, not having been paid, the soldiers of Genoa would help the Muslims in the coming battle, as had happened during the time of Alfonso X.[50]

The king resolved to pay the soldiers of Genoa from his own resources, and the soldiers decided to continue the siege and remain loyal to the king. An important factor was the loans that Genoese merchants made to the King of Castile during the siege, which allowed him to quell the complaints of his soldiers.[51] The two squadrons did not meet in the bay, but the ships commanded by the Sultan of Morocco docked in the city of Gibraltar, where they left a large number of soldiers: forty thousand infantry and twelve thousand horsemen according to some chroniclers.[52]

In November the Sultan of Granada and the Prince of Morocco advanced to the bank of the Río Palmones. The movement of troops from Gibraltar to the Palmones were protected by a squadron of ships of the Emir of Morocco, which stood in the middle of the bay to prevent the Castilian-Aragonese fleet from landing troops to oppose them. The Castilian command then ordered attempts to set fire to the enemy ships by means of vessels full of flammable material and burning arrows, taking advantage of the strong east wind that was blowing. The Muslims avoided the fire by placing wet sails on deck and using long poles to fend off the enemy ships.[52]

The Castillian command had been warned of the arrival of the troops by signals to the Tower of Champions. The Islamic army sent a first expeditionary force across the river to reconnoiter the Castilians, which was observed from the tower. Alfonso XI ordered that none of his men attack the Granadans until all their troops had crossed the river. The Muslims also knew the terrain and after an initial inspection and a minor brush with a small group of Christians, returned to their side of the river waiting for news.[53] At the Granada camp they were in no hurry to start fighting because in a few days they would receive reinforcements from their capital, and could then face the Castilians.

Battle of the River Palmones: December 1343

On 12 December 1343 the raids against the walls of the city were especially strong. The city was using "thunder" to bombard the Christian camp from cannons, while in return the Christians launched many arrows against the defenders. Shortly after dawn the Christian siege weapons made a break in the defenses, and through it an attack was launched on the city, but the besiegers were not able to penetrate. At this point the defenders of Algeciras in panic made smoke signals from the tower of the main mosque of the city indicating that the situation was untenable. At the camp of Granada they saw the signals, heard the noise, and understood that the city was being attacked.[54] The Moorish troops from Gibraltar were quickly mobilized to join those who were in combat formation beside the Río Palmones.[55]

From the Tower of the Champions, Alfonso XI directed his army to form. Don Joan Núñez was placed at the place where the river could be crossed near the mountains. Muslim troops that passed the ford had to battle the Spaniards, and were overwhelmed by the large numbers of troops that had come from the tower. Under the command of the King, all the Christian troops crossed the river and pursued the Moorish forces in their retreat. The Muslim cavalry were soon badly depleted. The Moors fled in disorder, ignoring orders to withdraw to Gibraltar. Many fled to the mountains of Algeciras, others towards the Almoraima tower, pursued by the Castilians.[56]

The allied forces of Granada and Morocco had been defeated, but Río Palmones marshes contained many corpses from both sides. It was not a total defeat and there was a possibility that the Muslims would reorganize their troops. The Christians needed the city to fall soon.[56]

Blockade and capitulation: January 1344 – March 1344

After the disastrous battle of the river Palmones, the sultan of Granada wanted to prepare a second attack on the Christian hosts, but the morale of the troops was low. The emissary of the Moroccan Sultan convinced him to try to resolve the conflict with the King of Castile by a peace treaty, and a letter was sent to the Christians at Algeciras offering a truce, but Alfonso XI did not want peace on any terms other than that the city became part of his kingdom.[54]

In January 1344 Alfonso decided to restore the naval boom, since the blockade was often violated by small boats from Gibraltar. The new barrier was formed by strong ropes supported by floating barrels, maintained in position by ship masts weighted at one end with millstones and with the other end protruding several meters from the sea surface.[38] Installation of the barrier took two months, during which there was continued violation by small boats.[57] In January the Muslims sent a ship loaded with provisions, but it was captured before it could reach the city. Another attempt in February was successful.[58] On 24 February five boats reached Algeciras with provisions. The passage of boats into the city of Algeciras was definitely cut off in early March.[38] It was now only a matter of time before hunger forced the city to capitulate or to offer a satisfactory agreement to the besiegers.[57]

By March, the situation in the city was desperate. There was no bread or any other food for its people, and only enough defenders to cover part of the wall. On Sunday 2 March Hazán Algarrafe, sent by the King of Granada, arrived with news for the King of Castile: the King of Granada was prepared to surrender the city. His conditions were simple: all who remained in the city should be allowed to leave under the protection of Alfonso XI with all their belongings; there would be a fifteen-year truce between Castile and the Moorish kingdoms; Granada would pay an annual tribute of twelve thousand doubloons of gold to Castile.[59]

The king's knights recommended continuing the siege, since reinforcements would soon arrive from Seville and Toledo, and the trenches around the city ensured that it would soon be starving. However, Alfonso XI did not want to continue fighting since the cost was so high in both money and lives. He accepted the proposed conditions apart from the duration of the truce, which would be for only ten years.[59] The Treaty of Algeciras was then signed, ending twenty one months of siege.[60]

On 26 March 1344 the inhabitants of Villa Nueva passed, with their belongings, to the Villa Vieja, yielding the Villa Nueva to the prince Don Juan Manuel. The next day, the eve of Palm Sunday, the Villa Vieja was handed over to King Alfonso XI empty of its occupants. The towers of the city were decked with the banners of the king, the prince Don Pedro, Don Enrique, the Master of Santiago, Don Fernando, Don Tello and Don Juan. Accompanying the delegation were the king's main commanders, including Egidio Boccanegra, who was appointed Lord of the Estado de la Palma in appreciation for his work in the encirclement.[61] The next day a mass was held in the mosque of the city, consecrated as a cathedral dedicated to Santa Maria de La Palma, still the patron saint of the city.[62] An Arab historian recorded that Alfonso gave good treatment to the Moorish generals and the inhabitants who were expelled from the city.[63] Many of them moved across the bay to Gibraltar, swelling the population of that remaining stronghold of the Sultan of Morocco.[64]

Castilian nobles who had died in the siege included Rui López de Rivera, former Castilian ambassador in Morocco, Diego López de Zúñiga y Haro, lord of La Rioja, Gonzalo Yáñez de Aguilar and Fernán González de Aguilar, lords of Aguilar, among others.[65]

Aftermath

The fall of Algeciras was a decisive step in the Reconquista, giving the Crown of Castile the main port on the north coast of the Strait of Gibraltar. To ensure the prosperity of the new Castilian city, in 1345 King Alfonso XI issued a charter that provided farmland and tax benefits to anyone who wanted to settle in the city.[66] He added "King of Algeciras" to his titles, and asked Pope Clement VI to move the Cathedral of Cádiz to Algeciras, creating the diocese of Cadiz and Algeciras and converting the main mosque of the city into a cathedral dedicated to the Virgen de la Palma.[67][68] The city would thereafter be the primary basis of action of the Christian armies.

After the loss of Al-Jazeera Al-Khadra, the only remaining Iberian port of Morocco was Gibraltar. All the efforts of the reconquest would now focus on taking this port. In 1349 Alfonso XI began the Fifth Siege of Gibraltar, again relying on the fleets of Aragon and Genoa, which established their main base in Algeciras, but this time the fate of the city did not depend on military actions: on 26 March of that year the king died during an epidemic of bubonic plague in the Castilian camp.[69]

This unexpected death resulted in a civil war among claimants to the throne of Castile. The consequences of the war on Algeciras were swift. In 1369, during the war between Peter the Cruel and his brother Henry II, the garrison was reduced and some of the troops sent north. Muhammed V, Sultan of Granada, took the opportunity to recapture Al-Jazeera Al-Khadra.[70] The Muslims rebuilt the defenses and established a large force to defend the city.[71]

The fate of the city changed again with the end of the disputes in Castile. In 1379, when the Christian armies regrouped, the Moors foresaw their inability to defend the city in case of another siege, and the danger if it again fell into Castilian hands. That year they undertook the destruction of the city.[71] They threw down the harbor walls and burned all buildings. In three days Algeciras was completely destroyed. It would remain so until the British conquest of Gibraltar in 1704, when some of the exiles from Gibraltar settled the barren fields of the former Villa Vieja.[72]

Notes and references

Notes

- The alcabala tax was extended in 1345 after the fall of the city to cover the cost of defending Algeciras and to fund the Fifth Siege of Gibraltar.[8]

- The Master of the Order of Santiago, Alfonso Méndez de Guzmán, was the brother of the mistress of Alfonso XI.[23] After he died, Alsonso installed his illegitimate son, the young Infante Don Fadrique, as the new master.[24]

Citations

- Tarifa y el Poema de Alfonso XI.

- Pérez Rosado 2013.

- Jiménez-Camino Álvarez & Tomassetti Guerra 2005, p. 5.

- Andalucia entre Oriente y Occidente, p. 108.

- Montero 1860, p. 144.

- Torremocha Silva & Sáez Rodríguez 2001, p. 199.

- Santacana y Mensayas 1901, p. 50.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 243.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 487.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 489.

- Montero 1860, p. 149.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 490.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 492.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 493.

- Jiménez-Camino Álvarez & Tomassetti Guerra 2005, p. 12.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 494.

- Jiménez-Camino Álvarez & Tomassetti Guerra 2005, p. 11.

- Jiménez-Camino Álvarez & Tomassetti Guerra 2005.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 496.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 497.

- Torremocha Silva 2004, p. s1.1.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 196.

- Gallego Blanco 1971, p. 27.

- Gallego Blanco 1971, p. 28.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 502.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 504.

- Salazar y Castro 1697, p. 203.

- Rojas Gabriel 1972, p. 887.

- O'Callaghan 2011, p. 197.

- Torremocha Silva 2004, p. s1.3.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 515.

- Montero 1860, p. 152.

- Torremocha Silva 2004, p. 1.2.

- Torremocha Silva 2004, p. s1.4.

- Rojas Gabriel 1972, p. 883.

- Prescott 1854, p. 215.

- Del Pulgar 1780, p. 304.

- Torremocha Silva 2004, p. s2.

- Torremocha Silva & Sáez Rodríguez 2001, p. 203.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 542.

- Stephens 1873, p. 165.

- Montero 1860, p. 153.

- Torremocha Silva 1987, p. 248.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 561.

- Montero 1860, p. 154.

- Torremocha Silva 2000, p. 440.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 567.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 568.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 589.

- Calderón Ortega 2001, p. 331.

- Torremocha Silva 2000, p. 442.

- Montero 1860, p. 156.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 601.

- Lafuente Alcántara 1852, p. 391.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 609.

- Montero 1860, p. 158.

- Torremocha Silva 1987, p. 252.

- O'Callaghan, Kagay & Vann 1998, p. 160.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 621.

- Torremocha Silva & Sáez Rodríguez 2001, p. 204.

- Ortiz de Zúñiga 1795, p. 304.

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno, p. 623.

- Stephens 1873, p. 166.

- Stephens 1873, p. 167.

- Ortiz de Zúñiga 1795, p. 112.

- Torremocha Silva & Sáez Rodríguez 2001, p. 278.

- Torremocha Silva & Sáez Rodríguez 2001, p. 310.

- Igartuburu 1847, p. 121.

- Sayer 1862, p. 47.

- García Torres 1851, p. 376.

- Olmedo 2006, p. 20.

- Madoz 1849, p. 567.

Sources

- Andalucia entre Oriente y Occidente (1236–1492) : actas del quinto coloquio internacional de historia medieval de Andalucia (in Spanish). 1988. p. 108. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- Calderón Ortega, José Manuel (2001). "Los almirantes del "siglo de oro" de la Marina castellana medieval" (PDF). España Medieval (in Spanish) (24). ISSN 0214-3038.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crónica de Alfonso Onceno. Madrid: Imprenta de Don Antonio de Sancha (Francisco Cerdá y Rico Second edition). 1787. pp. 630.

- Del Pulgar, Hernando (1780). Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón (in Spanish). Imprenta de Benito Monfort. p. 304.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gallego Blanco, Enrique (1971). The Rule of the Spanish Military Order of St. James. Brill Archive. GGKEY:J904YWQAEF2. Retrieved 21 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- García Torres, Vicente (1851). Instrucción para el pueblo: Colección de tratados sobre todos los conocimientos humanos (in Spanish).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Igartuburu, Luis de (1847). Manual de la provincia de Cádiz: Trata de sus límites, su categoría, sus divisiones en lo Civil, Judicial, militar i eclesiástico para la Protección I Seguridad Pública (in Spanish). Imprenta de la revista médica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jiménez-Camino Álvarez, Rafael; Tomassetti Guerra, José María (2005). ""Allende el río..." sobre la ubicación de las villas de Algeciras en la Edad Media". Boletín de arqueología yazirí (in Spanish) (1). pp.435–457.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lafuente Alcántara, Miguel (1852). Historia de Granada (in Spanish). 1. Paris: Baudry, Librería europea.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madoz, Pascual (1849). Diccionario geográfico-estadístico-histórico de España y sus posesiones de Ultramar (in Spanish). Imprenta del diccionario geográfico.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Montero, Francisco María (1860). Historia de Gibraltar y su campo (in Spanish). Cádiz: Imprenta de la revista médica. pp. 454.

historia de gibraltar y de su campo.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - O'Callaghan, Joseph F.; Kagay, Donald J.; Vann, Theresa M. (1998). On the Social Origins of Medieval Institutions: Essays in Honor of Joseph F. O'Callaghan. BRILL. p. 160. ISBN 978-90-04-11096-0. Retrieved 21 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Callaghan, Joseph (17 March 2011). The Gibraltar Crusade: Castile and the Battle for the Strait. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0463-6. Retrieved 21 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olmedo, Fernando (2006). Ruta de los almorávides y almohades: De Algeciras a Granada por Cádiz, Jerez, Ronda y Vélez-Málaga: gran itinerario cultural del Consejo de Europa (in Spanish). Fundación El legado andalusì. ISBN 84-96395-13-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ortiz de Zúñiga, Diego (1795). Anales eclesiásticos y seculares de la muy noble y muy leal ciudad de Sevilla (in Spanish). Imprenta Real.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pérez Rosado, D. Miguel (2013). "Poesía medieval español, la épica" (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prescott, William Hickling (1854). History of the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic, of Spain. p. 215. Retrieved 22 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rojas Gabriel, Manuel (1972). "Guerra de asedio y expugnación castral en la frontera con Granada]" (PDF). Guerra y frontera en la Edad Media peninsular (in Spanish). Revista da Facultade de Letras (1). ISSN 0871-164X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salazar y Castro, Luis (1697). Historia Genealógica de la Casa de Lara justificada con instrumentos, y escritores de inviolable fe (in Spanish). en la Imprenta Real, por Mateo de Llanos y Guzman. p. 203. Retrieved 21 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Santacana y Mensayas, Emilio (1901). Antiguo y moderno Algeciras (in Spanish). Algeciras: Tipografía El Porvenir. ISBN 84-88556-21-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Segura González, Wenceslao. "Tarifa y el Poema de Alfonso XI". Aljaranda (in Spanish).

- Sayer, Frederick (1862). The History of Gibraltar and of Its Political Relation to Events in Europe. Saunders.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stephens, F.G. (1873). A History of Gibraltar and Its Sieges. Provost. Retrieved 21 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Torremocha Silva, Antonio (1987). "La técnica militar aplicada aplicada al cerco y defensa de ciudades a mediados del siglo XIV" (PDF). Estudios de historia y de arqueología medievales (in Spanish) (7–8). ISSN 0212-9515.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Torremocha Silva, Antonio (2000). "Relaciones comerciales entre la corona de Aragón y Algeciras a mediados del siglo XIV". UNED. Tiempo y Forma, Serie III, Historia Medieval (in Spanish). 13. pp.435–457. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Torremocha Silva, Antonio; Sáez Rodríguez, Ángel (2001). Historia de Algeciras (in Spanish). I. Cádiz: Diputación de Cádiz. pp. 177–323. ISBN 84-95388-35-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Torremocha Silva, Antonio (2004). "Cerco y defensa de Algeciras: el uso de la pólvor". Centro de estudios moriscos de Andalucía (in Spanish).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Poema de Alfonso Onceno, Alicante, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2008. Reproducción digital de la ed. facsímil de Tomás Antonio Sánchez, Poetas castellanos anteriores al siglo XV, Madrid, Rivadeneyra, 1864, págs. 477–551. (Biblioteca de Autores Espyearles, 58).

- De Castro y Rossy, Adolfo (1858). Historia de Cádiz y su provincia (in Spanish). Cádiz: Imprenta de la Revista Médica.

- Torremocha Silva, Antonio; et al. (1999). Al-Binya, La Ciudad Palatina Meriní de Algeciras (in Spanish). Algeciras: Fundación municipal de cultura José Luis Cano. ISBN 978-84-89227-20-0.

- Requena, Fermín (1956). Muhammad y Al-Qasim "Emires de Algeciras" (in Spanish). Tipografía San Nicolás de Bari.

- Delgado Gómez, Cristóbal (1971). Algeciras, pasado y presente de la ciudad de la bella bahía (in Spanish). Algeciras: Gráficasal. ISBN 978-84-400-2196-0.

- Torremocha Silva, Antonio (1993). Algeciras, Entre la Cristiandad y el Islam (in Spanish). Instituto de Estudios Campogibraltareños. ISBN 84-88556-07-1.

- García Jiménez, Guillermo (1989). Capricho árabe (in Spanish). Algeciras: Alba S.A. ISBN 84-86209-22-6.

- Razouk, Mohammed. "Observaciones acerca de la contribución meriní para la conservación de las fronteras del Reino de Granada". Actas del Congreso la frontera Oriental Nazarí como sujeto histórico (s. XIII-XIV) (in Spanish). ISBN 84-8108-141-8.