Šibenik

Šibenik (Croatian pronunciation: [ʃîbeniːk] (![]()

Šibenik | |

|---|---|

| Grad Šibenik City of Šibenik | |

.jpg) _-_panoramio.jpg)    Clockwise from top: View of the town from the St. Michael's Fortress; Cathedral of St. James; Medieval Mediterranean Garden of St. Lawrence's Monastery; Croatian National Theatre in Šibenik; Riva in Šibenik; Šibenik Town Hall | |

Flag  Seal | |

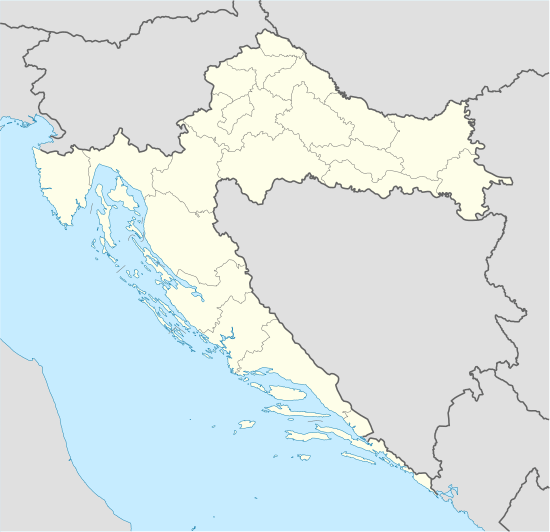

Šibenik Location of Šibenik within Croatia | |

| Coordinates: 43°44′N 15°55′E | |

| Country | |

| County | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Željko Burić (HDZ) |

| • City Council | 25 members

|

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • City | 34,302 |

| • Metro | 46,332 |

| Demonym(s) | Šibenčanin / Šibenčanka (cr) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | HR-22 000 |

| Area code(s) | +385 22 |

| License plate | ŠI |

| Climate | Csa |

| Website | http://www.sibenik.hr/ |

History

Etymology

There are multiple interpretations of how Šibenik was named. In his fifteenth century book De situ Illiriae et civitate Sibenici, Juraj Šižgorić describes the name and location of Šibenik. He attributes the name of the city to it being surrounded by a palisade made of šibe (sticks, singular being šiba).[2] Another interpretation is associated with the forest through the Latin toponym "Sibinicum," which covered a narrower microregion within Šibenik on and around the area of St. Michael's Fortress.[3]

Early history

Unlike other cities along the Adriatic coast, which were established by Greeks, Illyrians and Romans, Šibenik was founded by Croats.[4] Excavations of the castle of St. Michael, have since proven that the place was inhabited long before the actual arrival of the Croats. It was mentioned for the first time under its present name in 1066 in a Charter of the Croatian King Petar Krešimir IV[4] and, for a period of time, it was a seat of this Croatian King. For that reason, Šibenik is also called "Krešimirov grad" (Krešimir's city).

Between the 11th and 12th centuries, Šibenik was tossed back and forth among Venice, Byzantium, and Hungary. It was conquered by the Republic of Venice in 1116,[5] who held it until 1124, when they briefly lost it to the Byzantine Empire,[6] and then held it again until 1133 when it was retaken by the Kingdom of Hungary.[7] It would change hands among the aforementioned states several more times until 1180.

The city was given the status of a town in 1167 from Stephen III of Hungary.[8] It received its own diocese in 1298.[4]

In the 14th century, "Vlachs" were present in the hinterland of Šibenik.

Under Venice and the Habsburgs

The city, like the rest of Dalmatia, initially resisted the Venetian Republic, but it was taken over after a three-year war in 1412.[4] Under Venetian rule, Šibenik became in 1412 the seat of the main customs office and the seat of the salt consumers office with a monopoly on the salt trade in Chioggia and on the whole Adriatic Sea.

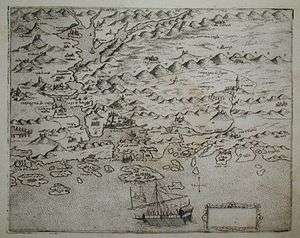

In August 1417, Venetian authorities were concerned with the "Morlachs and other Slavs" from the hinterland, that were a threat to security in Šibenik.[9] The Ottoman Empire started to threaten Šibenik (known as Sebenico), as part of their struggle against Venice, at the end of the 15th century,[5] but they never succeeded in conquering it. In the 16th century, St. Nicholas Fortress was built and, by the 17th century, its fortifications were improved again by the fortresses of St. John (Tanaja) and Šubićevac (Barone).

The Morlachs started settling Šibenik during the Cretan War (1645–69).[10]

The fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797 brought Sebenico under the authority of the Habsburg Monarchy.[5]

After the Congress of Vienna until 1918, the town was (again) part of the Austrian monarchy (Austria side after the compromise of 1867), head of the district of the same name, one of the 13 Bezirkshauptmannschaften in Kingdom of Dalmatia.[11] The Italian name only was used until around 1871.

In 1872, at the time in the Kingdom of Dalmatia, Ante Šupuk became the town's first Croat mayor elected under universal suffrage. He was instrumental in the process of the modernization of the city, and is particularly remembered for the 1895 project to provide street lights powered by the early AC Jaruga Hydroelectric Power Plant. On 28 August 1895, Šibenik became the world's first city with alternating current-powered street lights.[12]

20th century

During World War I, the Austro-Hungarian navy used the port facilities here, and the light cruisers and destroyers which escaped the Allied force after the battle of Cape Rodoni (or Gargano) returned to safety here, where some battleships were based.[13] After the war Šibenik was occupied by the Kingdom of Italy until 12 June 1921. As a result of the Treaty of Rapallo, the Italians gave up their claim to the city and it became a part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. During World War II it was occupied by Italy and Germany. Communist partisans liberated Šibenik on 3 November 1944.

After World War II it became a part of the SFR Yugoslavia until Croatia declared independence in 1991.

During the Croatian War of Independence (1991–95), Šibenik was heavily attacked by the Yugoslav National Army and Serbian paramilitary troops.[5] Although under-armed, the nascent Croatian army and the people of Šibenik managed to defend the city. The battle lasted for six days (16–22 September), often referred to as the "September battle". The bombings damaged numerous buildings and monuments, including the dome of the Cathedral of St. James and the 1870-built theatre building.

In an August 1995 military operation, the Croatian Army defeated the Serb forces and reconquered the occupied areas,[5] which allowed the region to recover from the war and continue to develop as the centre of Šibenik-Knin county. Since then, the damaged areas of the city have been fully restored.

Climate

Šibenik has a mediterranean climate (Csa), with mild, humid winters and hot, dry summers. January and February are the coldest months, July and August are the hottest months. In July the average maximum temperature is around 30 °C (86 °F). The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Csa" (Mediterranean Climate).[14]

| Climate data for Šibenik | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.2 (100.8) |

39.4 (102.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

30.3 (86.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.2 (13.6) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74.1 (2.92) |

60.1 (2.37) |

62.0 (2.44) |

62.7 (2.47) |

49.0 (1.93) |

53.0 (2.09) |

29.7 (1.17) |

44.9 (1.77) |

75.5 (2.97) |

82.7 (3.26) |

112.4 (4.43) |

95.2 (3.75) |

801.3 (31.57) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 105 |

| Average snowy days | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 128.6 | 150.6 | 196.1 | 222.4 | 286.3 | 312.1 | 358.0 | 326.0 | 254.3 | 199.7 | 131.0 | 113.8 | 2,678.9 |

| Source: National Meteorological and Hydrological Service (Croatia) [15] | |||||||||||||

Main sights

The central church in Šibenik, the Cathedral of St. James, is on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Several successive architects built it completely in stone between 1431 and 1536,[4] both in Gothic and in Renaissance style. The interlocking stone slabs of the cathedral's roof were damaged when the city was shelled by Yugoslav forces in 1991. The damage has since been repaired.

Fortifications in Šibenik

| Cathedral of St. James | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Location | Šibenik, Croatia |

| Built | 1431-1536 |

| Architectural style(s) | Renaissance |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Designated | 2000 (24th Session) |

| Reference no. | 963 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| St. Nicholas Fortress | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Šibenik, Croatia |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 2017 (41 Session) |

| Part of | Venetian Works of Defence between 15th and 17th centuries: Stato da Terra – western Stato da Mar |

| Reference no. | 1533 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

In the city of Šibenik there are four fortresses, each of which has views of the city, sea and nearby islands. The fortresses are now tourist sightseeing destinations.

- St. Nicholas Fortress (Croatian: Tvrđava Sv. Nikole) is a fortress located on the island of Ljuljevac,at the entrance to the St. Anthony Channel, across from the Jadrija beach lighthouse. It is included in UNESCO's World Heritage Site list as part of Venetian Works of Defence between 15th and 17th centuries: Stato da Terra – western Stato da Mar in 2017.[16]

- St. Michael's Fortress in historic town centre

- St. John Fortress

- Barone Fortress

Natural heritage

- Roughly 18 kilometres (11 mi) north of the city is the Krka National Park, similar to the Plitvice Lakes National Park, known for its many waterfalls, flora, fauna, and historical and archaeological remains.

- The Kornati archipelago, west of Šibenik, consists of 150 islands in a sea area of about 320 km2 (124 sq mi), making it the densest archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea.[17]

Culture and events

The annual Šibenik International Children's Festival (Međunarodni Dječji Festival) takes place every summer and hosts children's workshops, plays and other activities. From 2011 to 2013 the Terraneo festival (music festival) was held in August on a yearly basis on a former military area in Šibenik, and since 2014 Šibenik (and other nearby towns) are the home of its spiritual successor Super Uho festival. The composer Jakov Gotovac founded the city's "Philharmonia Society" in 1922. The composer Franz von Suppé was part of the city's cultural fabric, as he was a native of nearby Split. Each summer, a lot of concerts and events take place in the city (especially on the St. Michael Fortress). Also, starting in 2016 on a nearby island of Obonjan (6 kilometres (3.7 miles) southwest of the city) is held music, art, health and workshop festival.

Šibenik chanson festival is a musical event of a long tradition that takes place in Šibenik in the second half of month August.[18]

Sports

A famous sports town, Šibenik is the hometown of many successful athletes such as: Aleksandar and Dražen Petrović, Perica Bukić, Ivica Žurić, Predrag, Veselinka and Dario Šarić, Vanda Baranović-Urukalo, Danira Nakić, Nik Slavica, Miro Bilan, Dražan Jerković, Petar Nadoveza, Krasnodar Rora, Dean Računica, Mladen Pralija, Ante Rukavina, Duje Ćaleta-Car, Mile Nakić, Franko Nakić, Siniša Belamarić, Renato Vrbičić, Ivica Tucak, Andrija Komadina, Miro Jurić, Antonio Petković, Neven Spahija, Antonija Sandrić, Mate Maleš, Stipe Bralić and many others.

Basketball

The famous multi-purpose hall located in the Baldekin neighborhood, called Baldekin Sports Hall has been the home arena of GKK Šibenka, that is a successor to KK Šibenik, the famous basketball club which has played in the final of the FIBA Korać Cup twice and in the final of the 1982–83 Yugoslav League. The team was leading by then 19-year-old Dražen Petrović.

The women's basketball club, ŽKK Šibenik, is the most successful club in Croatia, winning the Yugoslav League in 1991, Croatian Championship four times, Yugoslav Cup twice, Croatian Cup four times, Adriatic League five times and the Vojko Herksel Cup four times.

The dissolved men's basketball club, Jolly Jadranska Banka, has played the semifinal of the Croatian Championship twice and the Krešimir Ćosić Cup final in the 2016–17 season.

Football

Šubićevac Stadium, located in the neighborhood of the same name has been the home ground of the football club HNK Šibenik, that has played many years in the Yugoslav Second League and later many years in the Croatian First League. In the 2009–10 season, the club played in the Croatian Cup final which they lost to the powerhouse Hajduk Split. Today, it also competes in the Croatian First League.

Water polo

VK Šibenik, the dissolved water polo club, is considered one of the best clubs in former Yugoslavia, winning the second place in the 1986–87 domestic league season. It also has played in the LEN Euro Cup final in the 2006–07 season, but lost to Sintez Kazan, as well as the club played in the LEN Champions League in the 2008–09 season, led both times by Ivica Tucak, today the head coach for the senior men's Croatia national team.

Perica Bukić and Renato Vrbičić are Olympic medalists, winning the gold medal at the 1996 Summer Olympics held in Atlanta, representing the Croatia national team. Ivica Tucak has been the most successful coach of the senior men's Croatia national team ever.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1961 | 44,440 | — |

| 1971 | 47,122 | +6.0% |

| 1981 | 51,445 | +9.2% |

| 1991 | 55,842 | +8.5% |

| 2001 | 51,553 | −7.7% |

| 2011 | 46,332 | −10.1% |

| Source: Naselja i stanovništvo Republike Hrvatske 1857–2001, DZS, Zagreb, 2005 | ||

In the 2011 Croatian census, Šibenik's total city population is 46,332 which makes it the tenth-largest city in Croatia, with 34,302 in the urban settlement.[1]

Of Šibenik's citizens, 94.02% were ethnic Croats.

The list of settlements is as follows:[1]

- Boraja, population 249

- Brnjica, population 72

- Brodarica, population 2,534

- Čvrljevo, population 64

- Danilo, population 376

- Danilo Biranj, population 442

- Danilo Kraljice, population 104

- Donje Polje, population 267

- Dubrava kod Šibenika, population 1,185

- Goriš, population 147

- Gradina, population 303

- Grebaštica, population 937

- Jadrtovac, population 171

- Kaprije, population 189

- Konjevrate, population 173

- Krapanj, population 170

- Lepenica, population 68

- Lozovac, population 368

- Mravnica, population 70

- Perković, population 111

- Podine, population 26

- Radonić, population 79

- Raslina, population 567

- Sitno Donje, population 561

- Slivno, population 110

- Šibenik, population 34,302

- Vrpolje, population 776

- Vrsno, population 67

- Zaton, population 978

- Zlarin, population 284

- Žaborić, population 479

- Žirje, population 103

Economy

Port

Šibenik is one of the best protected ports on the Croatian Adriatic and is situated on the estuary of the Krka River. The approach channel is navigable by ships up to 50,000 tonnes deadweight. The port itself has depths up to 40 m.[19]

International relations

Šibenik is twinned with:

Image gallery

Šibenik harbor

Šibenik harbor Sunrise in Šibenik

Sunrise in Šibenik.jpg) Square of the Republic of Croatia

Square of the Republic of Croatia Šibenik Cathedral

Šibenik Cathedral- Cannons in Šibenik

The City "New Gate" (16th century)

The City "New Gate" (16th century)- Town Hall

Šibenik City Library

Šibenik City Library "Šibenik City Guard" - a historical military unit

"Šibenik City Guard" - a historical military unit

Šibenik sunset

Šibenik sunset View from Banj beach to St. Anthony Channel

View from Banj beach to St. Anthony Channel Fountain located in the Robert Visiani Park

Fountain located in the Robert Visiani Park Šibenik coast

Šibenik coast Šibenik sea including Banj beach and Šibenik Bridge

Šibenik sea including Banj beach and Šibenik Bridge St. John's Church - bell tower

St. John's Church - bell tower Entrance to the church of St. Francis

Entrance to the church of St. Francis Pellegrini Palace

Pellegrini Palace Sunset over St. Anthony's Channel

Sunset over St. Anthony's Channel Banj beach's traditional New Year's Day swimming

Banj beach's traditional New Year's Day swimming

References

- "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements, 2011 Census: Šibenik". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "O PODRIJETLU TOPONIMA ŠIBENIK (About the origins of the name Šibenik, in Croatian)".

- Monumenta spectantia historiam Slavorum meridionalium: Edidit Academia Scienciarum et Artium Slavorum Meridionalium, Volume 1. Croatia: Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti. 1868. p. 171.

- Foster, Jane (2004). Footprint Croatia, Footprint Handbooks, 2nd ed. p. 218. ISBN 1-903471-79-6

- Oliver, Jeanne (2007). Croatia. Lonely Planet 4th ed. p. 182. ISBN 1-74104-475-8

- Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1843). The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 26. Great Britain: C. Knight. p. 236. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- Giuseppe Praga, Franco Luxardo (1993). History of Dalmatia. Giardini. p. 91. ISBN 9788842702955. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- Robert Lambert Playfair (1881). Handbook to the Mediterranean. John Murray. p. 310. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- Fine 2006, p. 115.

- Tea Mayhew (2008). Dalmatia Between Ottoman and Venetian Rule: Contado Di Zara, 1645-1718. Viella. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-88-8334-334-6.

- Die postalischen Abstempelungen auf den österreichischen Postwertzeichen-Ausgaben 1867, 1883 und 1890, Wilhelm KLEIN, 1967

- "Prvi osvijetljeni grad u svijetu je naš Šibenik". Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). 16 July 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Noppen, Ryan K., Austro-Hungarian Cruisers and Destroyers 1914-18, Osprey Publishing UK, 2016, p.34. ISBN 978-1-4728-1470-8

- Climate Summary for Šibenik

- "Monthly Climate Values". Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Venetian Works of Defence between 15th and 17th centuries: Stato da Terra – western Stato da Mar". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Skračiċ, Vladimir (2003). Kornat Islands. Zadar: Forum. ISBN 953-179-600-9.

- "Šibenik Croatia - tourist destinations, information and attractions". www.sibenik-croatia.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Basic Information". www.portauthority-sibenik.hr.

- "Civitanova Marche — Twin Towns". Civitanova Marche. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- "45 ans de jumelage : Histoire de cités Le jumelage à Voiron" [45 years of twinning: The history of Voiron's twin towns]. Voiron Hôtel de Ville [Voiron council] (in French). Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- "Sibenik : (Croatie) Ville jumelée avec Voiron" [Šibenik, Croatia: Twin town of Voiron]. Voiron Hôtel de Ville [Voiron council] (in French). Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

Further reading

- Thomas Graham Jackson (1887), "Sebenico", Dalmatia, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OL 23292286M

- R. Lambert Playfair (1892), "Sebenico", Handbook to the Mediterranean (3rd ed.), London: J. Murray, OL 16538259M

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Šibenik. |

![]()