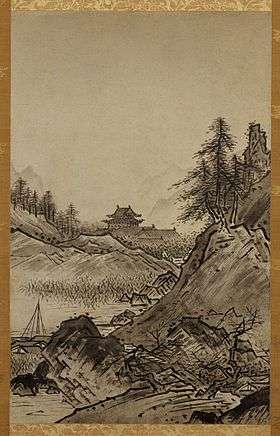

Ink wash painting

Ink wash painting (Chinese: 水墨畫; pinyin: shuǐmòhuà; Japanese: 水墨画, romanized: suiboku-ga; Korean: 수묵화, romanized: sumukhwa), or sumi-e (Japanese: 墨絵),[1] is a type of East Asian brush painting that uses black ink – as used in East Asian calligraphy – in different concentrations. Emerging in Tang dynasty China (618–907), it, and associated stylistic features, overturned earlier, more realistic techniques. These associated features include a preference for shades of black over variations in colour, and an emphasis on brushwork and the perceived "spirit" or "essence" of a subject over direct imitation.[2][3][4] It flourished in the Song dynasty China (960–1279), as well as in Japan after it was introduced by Zen Buddhist monks in the 14th century.[1]

| Ink wash painting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_-_right_hand_screen.jpg) Right panel of the Pine Trees screen (Shōrin-zu byōbu, 松林図 屏風) by Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539–1610). The painting has been designated as a National Treasure. | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 水墨畫 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 水墨画 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 수묵화 | ||||||

| Hanja | 水墨畵 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 1. 水墨画 2. 墨絵 | ||||||

| Hiragana | 1. すいぼくが 2. すみえ | ||||||

| |||||||

History

Brush painting was one of the "Four Arts" expected to be learnt by China's class of scholar-officials.[1] Ink wash painting appeared during the Tang dynasty (618–907), and its early development is credited to Wang Wei and Zhang Zao, among others.[4]

In the Ming dynasty, Dong Qichang would identify two distinct styles: a clearer, grander Northern School (北宗画 or 北画, C: Beizonghua or Beihua, J: Hokushūga or Hokuga), and a freer, more expressive Southern School (南宗画 or 南画, C: Nanzonghua or Nanhua, J: Nanshūga or Nanga), also called "Literati Painting" (文人画, C: Wenrenhua, J: Bunjinga).[2][5][6][7]

Philosophy

.jpg)

East Asian writing on aesthetics is generally consistent in stating that the goal of ink and wash painting is not simply to reproduce the appearance of the subject, but to capture its spirit. To paint a horse, the ink wash painting artist must understand its temperament better than its muscles and bones. To paint a flower, there is no need to perfectly match its petals and colors, but it is essential to convey its liveliness and fragrance. In this, it has been compared to the later Western movement of Impressionism.[2] It is also particularly associated with the Chán or Zen sect of Buddhism, which emphasises "simplicity, spontaneity and self-expression", and Daoism, which emphasises "spontaneity and harmony with nature,"[1] especially when compared with the less spiritually-oriented Confucianism.

In landscape painting the scenes depicted are typically imaginary, or very loose adaptations of actual views. Mountain landscapes are by far the most common, often evoking particular areas traditionally famous for their beauty, from which the artist may have been very distant. Water is very often included.

East Asian ink wash painting has long inspired modern artists in the West. In his classic book Composition, American artist and educator Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922) wrote this about ink wash painting: "The painter ... put upon the paper the fewest possible lines and tones; just enough to cause form, texture and effect to be felt. Every brush-touch must be full-charged with meaning, and useless detail eliminated. Put together all the good points in such a method, and you have the qualities of the highest art".[8] Dow's fascination with ink wash painting not only shaped his own approach to art but also helped free many American modernists of the era, including his student Georgia O'Keeffe, from what he called a "story-telling" approach. Dow strived for harmonic compositions through three elements: line, shading, and color. He advocated practicing with East Asian brushes and ink to develop aesthetic acuity with line and shading.

Technique

Ink wash painting uses tonality and shading achieved by varying the ink density, both by differential grinding of the ink stick in water and by varying the ink load and pressure within a single brushstroke. Ink wash painting artists spend years practicing basic brush strokes to refine their brush movement and ink flow. In the hand of a master, a single stroke can produce astonishing variations in tonality, from deep black to silvery gray. Thus, in its original context, shading means more than just dark-light arrangement: It is the basis for the beautiful nuance in tonality found in East Asian ink wash painting and brush-and-ink calligraphy.

Materials and tools

Ink wash painting is usually done on xuan paper (Chinese) or washi (Japanese paper) both of which are highly absorbent and unsized. Silk is also used in some forms of ink painting. Many types of xuan paper and washi do not lend themselves readily to a smooth wash the way watercolor paper does. Each brush stroke is visible, so any "wash" in the sense of Western style painting requires partially sized paper. Paper manufacturers today understand artists' demands for more versatile papers and work to produce kinds that are more flexible. If one uses traditional paper, the idea of an "ink wash" refers to a wet-on-wet technique, applying black ink to paper where a lighter ink has already been applied, or by quickly manipulating watery diluted ink once it has been applied to the paper by using a very large brush.

In ink wash paintings, as in calligraphy, artists usually grind inkstick over an inkstone to obtain black ink, but prepared liquid inks (墨汁 in Japanese, bokuju) are also available. Most inksticks are made of soot from pine or oil combined with animal glue. An artist puts a few drops of water on an inkstone and grinds the inkstick in a circular motion until a smooth, black ink of the desired concentration is made. Prepared liquid inks vary in viscosity, solubility, concentration, etc., but are in general more suitable for practicing Chinese calligraphy than executing paintings.[9] Inksticks themselves are sometimes ornately decorated with landscapes or flowers in bas-relief and some are highlighted with gold.

Ink wash painting brushes are similar to the brushes used for calligraphy and are traditionally made from bamboo with goat, cattle, horse, sheep, rabbit, marten, badger, deer, boar and wolf hair. The brush hairs are tapered to a fine point, a feature vital to the style of wash paintings.

Different brushes have different qualities. A small wolf-hair brush that is tapered to a fine point can deliver an even thin line of ink (much like a pen). A large wool brush (one variation called the big cloud) can hold a large volume of water and ink. When the big cloud brush rains down upon the paper, it delivers a graded swath of ink encompassing myriad shades of gray to black.

Once a stroke is painted, it cannot be changed or erased. This makes ink and wash painting a technically demanding art-form requiring great skill, concentration, and years of training.

Noted artists

China

India

Korea

- An Gyeon

- Byeon Sang-byeok

- Gang Hui-an

- Nam Gye-u

- Kim Hong-do

- Shin Yun-bok

- Owon

- Jeong Seon

See also

- Bird-and-flower painting

- Four Gentlemen

- Haboku

- Ink-wash animation

- Cantonese school of painting

- Higashiyama Bunka

- Shan shui

- Wash (visual arts)

- Modern European Ink Painting

References

- Dorothy Perkins (19 November 2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7.

- Sharron Gu (22 December 2011). A Cultural History of the Chinese Language. McFarland. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-7864-8827-8.

- Lu Yilong (30 December 2015). The History and Spirit of Chinese Art (2-Volume Set). Enrich Professional Publishing Limited. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-62320-130-2.

- The Editorial Committee of Chinese Civilization: A Source Book, City University of Hong Kong (1 April 2007). China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization. City University of HK Press. p. 732–3. ISBN 978-962-937-140-1.

- Watson, William, Style in the Arts of China, 1974, Penguin, p. 86, ISBN 0140218637

- Fred S. Kleiner (5 January 2009). Gardner's Art through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives. Cengage Learning. p. 81. ISBN 0-495-57367-1.

- Marco, Meccarelli. 2015. "Chinese Painters in Nagasaki: Style and Artistic Contaminatio during the Tokugawa Period (1603–1868)" Ming Qing Studies 2015, Pages 175–236.

- Dow, Arthur Wesley (1899). Composition.

- Okamoto, Naomi The Art of Sumi-e: Beautiful ink painting using Japanese Brushwork, Search Press, Kent UK, 2015, p. 16

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ink and wash paintings. |